Team:Paris Saclay/Modeling/bacterial Growth

From 2014.igem.org

m (→Simple birth-death process) |

(→Bacterial Population Growth) |

||

| (31 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

=Bacterial Population Growth= | =Bacterial Population Growth= | ||

| + | The oxygen diffusion model confirms the intuition we could have: while oxygen can't easily move into the medium, the growth on the surface is sufficiently more important than the growth inside the medium for neglecting the latter. We will tackle here the process of bacterial growth in different aspects. | ||

We are here considering a bacterial population uniformly spread on a surface in the Euclidean space, in crowd-free conditions and with unlimited food resources. | We are here considering a bacterial population uniformly spread on a surface in the Euclidean space, in crowd-free conditions and with unlimited food resources. | ||

| Line 9: | Line 10: | ||

Each time, we will expose both a deterministic model and a stochastic one. | Each time, we will expose both a deterministic model and a stochastic one. | ||

| - | The major advantage of the deterministic model is | + | The major advantage of the deterministic model is its simplicity. But this simplicity has a cost: while every set of variable states is uniquely determined by parameters in the model and by sets of previous states of these variables, the deterministic models perform the same way for a given set of initial conditions which is not really desirable. Conversely, in a stochastic model, randomness is present, and the variable states are not described by unique values, but rather by probability distributions. |

==Menu== | ==Menu== | ||

| Line 83: | Line 84: | ||

==Simple birth-death process== | ==Simple birth-death process== | ||

| - | In fact, the model we exposed in the previous part was not realistic and we have to consider that our bacteria could also die. We introduce here the death rate $\mu$ which is also supposed to be the same for all bacteria, regardless of their age and don't change with time. We still assume that bacteria develop | + | In fact, the model we exposed in the previous part was not realistic and we have to consider that our bacteria could also die. We introduce here the death rate $\mu$ which is also supposed to be the same for all bacteria, regardless of their age and don't change with time. We still assume that bacteria develop without interacting with each other. |

===Deterministic model=== | ===Deterministic model=== | ||

| - | We still have the same notation and $N(t)$ | + | We still have the same notation and $N(t)$ denotes the population size at time $t$. |

We proceed in a same way than in the pure birth process but, this time, death will lead to a decrease of the population, that's why the $\mu$ is preceded by a minus : | We proceed in a same way than in the pure birth process but, this time, death will lead to a decrease of the population, that's why the $\mu$ is preceded by a minus : | ||

| Line 104: | Line 105: | ||

====Establishment of the model==== | ====Establishment of the model==== | ||

| - | Analysis of the stochastic behaviour follows | + | Analysis of the stochastic behaviour follows exactly the same lines as for the pure birth process, except that in the short time $(t,t+h)$, there is now a probability $\lambda h$ that a particular bacterium gives birth ''and'' a probability $\mu h$ that it dies. With a population of size $N(t)$ at sime $t$, the probability that no events ocures is therefore $1-\lambda Nh-\mu Nh$, since $h$ is assumed to be sufficiently smal to ensure that the probability of more than one event occuring in $(t,t+h)$ is negligible. |

As state $N$ can be reached from states $N-1$ (by a birth), $N+1$ (by a death) or $N$ (either), we find : | As state $N$ can be reached from states $N-1$ (by a birth), $N+1$ (by a death) or $N$ (either), we find : | ||

| Line 196: | Line 197: | ||

Let ${\displaystyle M=\underset{n\in\mathbb{N}}{\sup}\max(1,\underset{x\in Supp(\phi_n)}\sup f(x))}$. And the Heine theorem assure that $M$ is finit. Actually, $f$ is continue on the compact $Supp(\phi_n)$ for all $n$ in $\mathbb{N}$ so is bound on it. By passing to the limit, we find | Let ${\displaystyle M=\underset{n\in\mathbb{N}}{\sup}\max(1,\underset{x\in Supp(\phi_n)}\sup f(x))}$. And the Heine theorem assure that $M$ is finit. Actually, $f$ is continue on the compact $Supp(\phi_n)$ for all $n$ in $\mathbb{N}$ so is bound on it. By passing to the limit, we find | ||

\[ {\displaystyle |~a(u,v)~|\leqslant (1+M)||u||_{\mathcal{H}^1_0}||\phi_n||_{\mathcal{H}^1_0}} \] | \[ {\displaystyle |~a(u,v)~|\leqslant (1+M)||u||_{\mathcal{H}^1_0}||\phi_n||_{\mathcal{H}^1_0}} \] | ||

| - | which is what we | + | which is what we were searching for. |

* '''$a$ is coercive''' : | * '''$a$ is coercive''' : | ||

| - | With a simular calculation, we show that $a$ is coercive, i.e that it exists a constant $\alpha$ in such a way that | + | With a simular calculation, we show that $a$ is coercive, i.e. that it exists a constant $\alpha$ in such a way that |

\[ \forall u \in \mathcal{H}^1_0(\mathbb{R}^2), \quad |a(u,u)| \geqslant \alpha ||u||^2 \] | \[ \forall u \in \mathcal{H}^1_0(\mathbb{R}^2), \quad |a(u,u)| \geqslant \alpha ||u||^2 \] | ||

So, according to the Lax-Milgram theorem | So, according to the Lax-Milgram theorem | ||

\[ \exists ! G\in\mathcal{H}^1_0,\quad\forall\phi\in\mathcal{H}^1_0,\quad a(G,\phi)=0 \] | \[ \exists ! G\in\mathcal{H}^1_0,\quad\forall\phi\in\mathcal{H}^1_0,\quad a(G,\phi)=0 \] | ||

| - | + | In other words, it means that, in the space of distributions, if we can exhibit a solution, it is the only solution of this problem. And the solution exists. | |

| - | If the solution we find is sufficiently regular (in a way to define more | + | If the solution we find is sufficiently regular (in a way to define more precisely), general theorems assure that the solution we find is not only a solution in the space of distributions but is also a solution in "the real life". |

Precisely, we can verify with a computation that, if $\lambda\neq\mu$ | Precisely, we can verify with a computation that, if $\lambda\neq\mu$ | ||

\[ \gamma(z,t)~:=~\left(\frac{\mu(1-z)-(\mu-\lambda z)e^{-(\lambda-\mu)t}}{\lambda(1-z)-(\mu-\lambda z)e^{-(\lambda-\mu)t}}\right)^{N_0} \] | \[ \gamma(z,t)~:=~\left(\frac{\mu(1-z)-(\mu-\lambda z)e^{-(\lambda-\mu)t}}{\lambda(1-z)-(\mu-\lambda z)e^{-(\lambda-\mu)t}}\right)^{N_0} \] | ||

| - | is solution to the equation, i.e that | + | is solution to the equation, i.e. that |

\[ \forall(z,t)\in\mathbb{R}^2, \partial t\gamma(z,t)+f(z,t)\partial z\gamma(z,t)=0 \] | \[ \forall(z,t)\in\mathbb{R}^2, \partial t\gamma(z,t)+f(z,t)\partial z\gamma(z,t)=0 \] | ||

| - | The computation is | + | The computation is very long and not really interesting (it suffices to derive $\gamma$ and substitute in the equation) that's why we will not detail it in this text... |

So, while the solution exists and is unique according to the Lax-Milgram theorem, if $\lambda\neq\mu$, we have found it and | So, while the solution exists and is unique according to the Lax-Milgram theorem, if $\lambda\neq\mu$, we have found it and | ||

| Line 220: | Line 221: | ||

====Coefficient of Variation $\star\star$==== | ====Coefficient of Variation $\star\star$==== | ||

| - | In this small | + | In this small part, we will just try to have an idea of the influence of the value of $\lambda$ and $\mu$ on the probability. To do that, we calculate the mean and the variance of population size. Actually, while we consider a discrete probability, |

\[ m(t) = \sum_{n=0}^{\infty}{n p_n(t)} = \ldots = N_0 e^{(\lambda-\mu)t} \] | \[ m(t) = \sum_{n=0}^{\infty}{n p_n(t)} = \ldots = N_0 e^{(\lambda-\mu)t} \] | ||

and by a similar calcul, if $\lambda\neq\mu$, | and by a similar calcul, if $\lambda\neq\mu$, | ||

\[ V(t) = N_0\frac{\lambda+\mu}{\lambda-\mu}e^{(\lambda-\mu)t}(e^{(\lambda-\mu)t}-1) \] | \[ V(t) = N_0\frac{\lambda+\mu}{\lambda-\mu}e^{(\lambda-\mu)t}(e^{(\lambda-\mu)t}-1) \] | ||

| - | Unlike $m(t)$ | + | Unlike $m(t)$, $V(t)$ depend not only on the difference between the birth and the death rates, but also on their absolute magnitudes. This is what we should expect, because predictions about the future size of a population will be less precise if birth and death occur in rapid succession than if they occur only occasionally. |

| - | We | + | We define the coefficient of variation $\displaystyle CV(t)~:=~\frac{\sqrt{V(t)}}{m(t)}$ which qualify the variation of the system and we will study the effect of the relative values of $\lambda$ and $\mu$. |

\[ \begin{array}{rcl} | \[ \begin{array}{rcl} | ||

\forall\lambda\neq\mu,~\forall t, CV(t) | \forall\lambda\neq\mu,~\forall t, CV(t) | ||

| Line 242: | Line 243: | ||

\[ CV(t)~\sim~\sqrt{\frac{\lambda+\mu}{N_0(\lambda-\mu)}}\times e^{\frac{1}{2}(\lambda-\mu)t} \] | \[ CV(t)~\sim~\sqrt{\frac{\lambda+\mu}{N_0(\lambda-\mu)}}\times e^{\frac{1}{2}(\lambda-\mu)t} \] | ||

| - | * We are now | + | * We are now interested in the coefficient of variation '''when $\lambda=\mu$'''. We cannot find an equivalent as easily as previously because $CV$, at least in that form , is not defined for $\lambda=\mu$. Actually, to know if $CV$ is defined or not when $\lambda=\mu$ is not really interesting because we want to have an idea of what will be the behaviour of $CV$ if $\lambda$ is so much close to $\mu$ that, biologically, they seem to be equal. It will be the same idea in the following part. |

| - | We remind that the function $\exp:x\rightarrow e^x$ is indefinitely differentiable, i.e $\exp\in\mathcal{C}^{\infty}$ so it admits a Taylor expansion in the neighbourhood of $0$ -in particular- : $\forall n\in\mathbb{N}$ and for $t$ sufficiently near to $0$, | + | We remind that the function $\exp:x\rightarrow e^x$ is indefinitely differentiable, i.e. $\exp\in\mathcal{C}^{\infty}$ so it admits a Taylor expansion in the neighbourhood of $0$ -in particular- : $\forall n\in\mathbb{N}$ and for $t$ sufficiently near to $0$, |

\[ \begin{array}{rcl} | \[ \begin{array}{rcl} | ||

e^t &=& {\displaystyle \exp(0)\frac{t^0}{0!}+\exp'(0)\frac{t^1}{1!}+\exp^{(2)}(0)\frac{t^2}{2!}+\exp^{(3)}\frac{t^3}{3!}+\ldots+\exp^{(n-1)}\frac{t^{n-1}}{(n-1)!}+\underset{t\rightarrow 0}{o}(t^n)} \\ | e^t &=& {\displaystyle \exp(0)\frac{t^0}{0!}+\exp'(0)\frac{t^1}{1!}+\exp^{(2)}(0)\frac{t^2}{2!}+\exp^{(3)}\frac{t^3}{3!}+\ldots+\exp^{(n-1)}\frac{t^{n-1}}{(n-1)!}+\underset{t\rightarrow 0}{o}(t^n)} \\ | ||

&=& {\displaystyle 1+t+\frac{t^2}{2}+\frac{t^3}{6}+\ldots+\frac{t^{n-1}}{(n-1)!}+\underset{t\rightarrow 0}{o}(t^n)} | &=& {\displaystyle 1+t+\frac{t^2}{2}+\frac{t^3}{6}+\ldots+\frac{t^{n-1}}{(n-1)!}+\underset{t\rightarrow 0}{o}(t^n)} | ||

\end{array} \] | \end{array} \] | ||

| - | So, by | + | So, by developing the exponents in the expression of $CV$, |

\[ \forall t\in\mathbb{R},~CV(t) ~=~ \sqrt{\displaystyle{\frac{\lambda+\mu}{N_0(\lambda-\mu)}}}\times\sqrt{1-(1-(\lambda-\mu)t)} +\underset{\lambda\rightarrow\mu}{o}(\sqrt{(\lambda-\mu)t})\] | \[ \forall t\in\mathbb{R},~CV(t) ~=~ \sqrt{\displaystyle{\frac{\lambda+\mu}{N_0(\lambda-\mu)}}}\times\sqrt{1-(1-(\lambda-\mu)t)} +\underset{\lambda\rightarrow\mu}{o}(\sqrt{(\lambda-\mu)t})\] | ||

| - | and cancelling the expression, we find | + | and cancelling the expression, we find |

\[ CV(t)~=~\sqrt{{\displaystyle\frac{(\lambda+\mu)t)}{N_0}}} +\underset{\lambda\rightarrow\mu}{o}(\sqrt{t}) \] | \[ CV(t)~=~\sqrt{{\displaystyle\frac{(\lambda+\mu)t)}{N_0}}} +\underset{\lambda\rightarrow\mu}{o}(\sqrt{t}) \] | ||

Finnaly, as $\lambda=\mu$, it comes that | Finnaly, as $\lambda=\mu$, it comes that | ||

| Line 258: | Line 259: | ||

[[File:Paris_Saclay_Simple_Birth_Death_Coefficient_of_Variation.png|660px|center]] | [[File:Paris_Saclay_Simple_Birth_Death_Coefficient_of_Variation.png|660px|center]] | ||

| - | At this point it is worth reflecting on | + | At this point it is worth reflecting on a criticism sometimes levelled against this model of exponential population growth, namely that if $\lambda$ exceeds $\mu$ then it ultimately leads to so large populations that their existence is physically impossible. |

| - | A far more serious, but often neglected, question is ''How far into the future is ecological prediction, based on simple models, feasible ?'' The answer must depend on the situation being considered, since it is influenced to a large extent by biological factors such as over what length of time the (actual) birth and death rates can be expected to remain reasonably constant and how large $N(t)$ may become before organisms can no longer be assumed to develop independently of each other. Clearly, whenever a biological process, no matter how innocently simple it may first | + | A far more serious, but often neglected, question is ''How far into the future is ecological prediction, based on simple models, feasible ?'' The answer must depend on the situation being considered, since it is influenced to a large extent by biological factors such as over what length of time the (actual) birth and death rates can be expected to remain reasonably constant and how large $N(t)$ may become before organisms can no longer be assumed to develop independently of each other. Clearly, whenever a biological process is being modelled, no matter how innocently simple it may first appear, the underlying assumption used in the construction of the model must be constantly questioned. The feasibly and predictable future may be well quickly disapointing. |

====Probability of extinction $\star$==== | ====Probability of extinction $\star$==== | ||

| Line 266: | Line 267: | ||

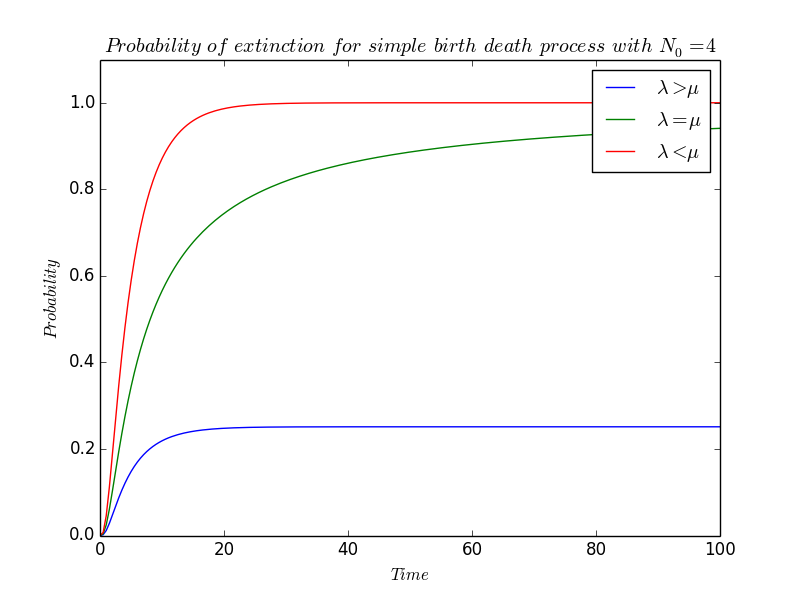

Last part but not least : we will study the probability of extinction of our bacteria population. | Last part but not least : we will study the probability of extinction of our bacteria population. | ||

| - | Intuitively, this probability will depend on $\lambda$ and $\mu$ : if $\lambda\ll\mu$, then it is reasonable to suppose that since death predominate the population will eventually | + | Intuitively, this probability will depend on $\lambda$ and $\mu$ : if $\lambda\ll\mu$, then it is reasonable to suppose that since death predominate the population will eventually die out, and since we have not considered immigration phenomenon, this implies ''extinction''. On the contrary, if $\lambda\gg\mu$ then birth predominate. Either an initial downward surge leads to extinction of the population, or else $N(t)$ avoids becoming zero and the population grows indefinitely. |

| - | The probability that extinction | + | The probability that extinction occur at or before $t$ is the coefficient before $z^0$ in $(\star)$, i.e, |

\[ \left(\frac{\mu-\mu e^{-(\lambda-\mu)t}}{\lambda-\mu e^{-(\lambda-\mu)t}}\right)^{N_0} \] | \[ \left(\frac{\mu-\mu e^{-(\lambda-\mu)t}}{\lambda-\mu e^{-(\lambda-\mu)t}}\right)^{N_0} \] | ||

where $N_0$ still refer to $N(0)$. | where $N_0$ still refer to $N(0)$. | ||

| - | In particular, this value for $N_0=1$ is the probability that a single bacterium | + | In particular, this value for $N_0=1$ is the probability that a single bacterium and all his clones are extinct at or before time $t$. |

| - | To obtain the probability of ''ultimate extinction'', $p_0(\infty)$, we have to let $t$ tend | + | To obtain the probability of ''ultimate extinction'', $p_0(\infty)$, we have to let $t$ tend to infinity and |

| Line 283: | Line 284: | ||

* On the contrary, '''if $\lambda\gneq\mu$''', then the exponential terms vanish, so | * On the contrary, '''if $\lambda\gneq\mu$''', then the exponential terms vanish, so | ||

\[ p_0(\infty)~\sim~\left(\frac{\mu}{\lambda}\right)^{N_0}\longrightarrow\left(\frac{\mu}{\lambda}\right)^{N_0} \] | \[ p_0(\infty)~\sim~\left(\frac{\mu}{\lambda}\right)^{N_0}\longrightarrow\left(\frac{\mu}{\lambda}\right)^{N_0} \] | ||

| - | In particular, even though $\lambda$ is greater than $\mu$, extinction can still | + | In particular, even though $\lambda$ is greater than $\mu$, extinction can still occur. It must append when $N_0$ is small or when $\displaystyle \frac{\mu}{\lambda}$ is near one. |

Thus, if we wish to choose $N_0$ to ensure that $p_0(\infty)\leqslant 10^{-3}$, then we require | Thus, if we wish to choose $N_0$ to ensure that $p_0(\infty)\leqslant 10^{-3}$, then we require | ||

\[ \left(\frac{\lambda}{\mu}\right)^{N_0}\geqslant 10^3 \] | \[ \left(\frac{\lambda}{\mu}\right)^{N_0}\geqslant 10^3 \] | ||

| - | i.e | + | i.e. |

\[ log_{10}\left(\left(\frac{\lambda}{\mu}\right)^{N_0}\right)~=~N_0 log_{10}\left(\frac{\lambda}{\mu}\right)\geqslant 3 \] | \[ log_{10}\left(\left(\frac{\lambda}{\mu}\right)^{N_0}\right)~=~N_0 log_{10}\left(\frac{\lambda}{\mu}\right)\geqslant 3 \] | ||

| - | and | + | and finally, |

\[ N_0\geqslant\frac{3}{log_{10}\left(\frac{\lambda}{\mu}\right)} \] | \[ N_0\geqslant\frac{3}{log_{10}\left(\frac{\lambda}{\mu}\right)} \] | ||

For example, if $\mu=1$ and | For example, if $\mu=1$ and | ||

\[ \lambda=1.01,\quad 2,\quad 10,\quad 100,\quad 1000, \] | \[ \lambda=1.01,\quad 2,\quad 10,\quad 100,\quad 1000, \] | ||

| - | $No$ must be | + | $No$ must be chosen such as |

\[ N_0\geqslant 695,\quad 73,\quad 10,\quad 3,\quad 2,\quad 1. \] | \[ N_0\geqslant 695,\quad 73,\quad 10,\quad 3,\quad 2,\quad 1. \] | ||

| - | * It is a little bit more difficult to determine $p_0(\infty)$ '''when $\lambda=\mu$''' because the expression $(\star\star)$ is not defined when $\lambda=\mu$. But, by reminding that the | + | * It is a little bit more difficult to determine $p_0(\infty)$ '''when $\lambda=\mu$''' because the expression $(\star\star)$ is not defined when $\lambda=\mu$. But, by reminding us that the exponential is $\mathcal{C}^\infty$ on $\mathbb{R}$ -particularly in $0$- and admit so a Taylor-expansion in the neighborhood of $0$ : |

\[ e^t~=~1+t+\frac{t^2}{2}+\frac{t^3}{6}+\frac{t^4}{24}+\ldots+\underset{t\rightarrow 0}{o}(t^n) \] | \[ e^t~=~1+t+\frac{t^2}{2}+\frac{t^3}{6}+\frac{t^4}{24}+\ldots+\underset{t\rightarrow 0}{o}(t^n) \] | ||

we can write $p_0$ as | we can write $p_0$ as | ||

| Line 305: | Line 306: | ||

As $t$ increases, | As $t$ increases, | ||

\[ p_0(t)~\underset{\begin{array}{c}{\scriptstyle \lambda\rightarrow\mu} \\ {\scriptstyle t\rightarrow\infty}\end{array}}\sim~\left(\frac{\mu t}{\mu t}\right)^{N_0}~\underset{\begin{array}{c}{\scriptstyle \lambda\rightarrow\mu} \\ {\scriptstyle t\rightarrow\infty}\end{array}}\longrightarrow~1 \] | \[ p_0(t)~\underset{\begin{array}{c}{\scriptstyle \lambda\rightarrow\mu} \\ {\scriptstyle t\rightarrow\infty}\end{array}}\sim~\left(\frac{\mu t}{\mu t}\right)^{N_0}~\underset{\begin{array}{c}{\scriptstyle \lambda\rightarrow\mu} \\ {\scriptstyle t\rightarrow\infty}\end{array}}\longrightarrow~1 \] | ||

| - | and so ultimate extinction is certain even | + | and so ultimate extinction is certain even if the birth rate and the death rate are equal. |

[[File:Paris_Saclay_Simple_Birth_Death_Probability_of_Extinction.png|660px|center]] | [[File:Paris_Saclay_Simple_Birth_Death_Probability_of_Extinction.png|660px|center]] | ||

| - | ==General conclusion : What about lemon ?== | + | ==General conclusion : What about lemon?== |

| - | To come back to our lemon, let see what | + | To come back to our lemon porject, let's see what is appening when we consider now "''our''" own bacteria and not only a general bacterium species ! |

| - | In practise, we use genetically modified ''E.coli''. As the modification that we carried out do not touch to the vital metabolism of bacteria we may assume that the | + | In practise, we use the genetically modified ''E.coli''. As the modification that we carried out do not touch to the vital metabolism of bacteria we may assume that the original rates of birth and death for ''E.coli'' have not been changed. |

| - | So, according to | + | So, according to researches of Eric Stewart [https://2014.igem.org/Team:Paris_Saclay/Modeling/bacterial_Growth#References [Ste]], we have |

\[ \lambda = 3,6 \times 10^{-2} ~ min^{-1} \] | \[ \lambda = 3,6 \times 10^{-2} ~ min^{-1} \] | ||

and | and | ||

| Line 321: | Line 322: | ||

| - | So we are in the case $\lambda>\mu$ | + | So we are in the case $\lambda>\mu$. The partition [https://2014.igem.org/Team:Paris_Saclay/Modeling/bacterial_Growth#Coefficient_of_Variation_.24.5Cstar.5Cstar.24 coefficient of variation] ensure us that the system is asymptotically stable. |

| - | + | Moreover, we know, through the part [https://2014.igem.org/Team:Paris_Saclay/Modeling/bacterial_Growth#Probability_of_extinction_.24.5Cstar.24 probability of extinction], that the probability of extinction is, if we denote $N_0$ the initial population size, | |

\[ p_0(\infty) \sim \left(\frac{\mu}{\lambda}\right)^{N_0} = \left(\frac{4,6 \times 10^{-4}}{\lambda = 3,6 \times 10^{-2}}\right)^{N_0} \simeq (1.3 \times 10^{-2})^{N_0} \simeq 10^{-2~N_0} \] | \[ p_0(\infty) \sim \left(\frac{\mu}{\lambda}\right)^{N_0} = \left(\frac{4,6 \times 10^{-4}}{\lambda = 3,6 \times 10^{-2}}\right)^{N_0} \simeq (1.3 \times 10^{-2})^{N_0} \simeq 10^{-2~N_0} \] | ||

| - | which is really near $0$. | + | which is really near to $0$. |

| - | In practice, there is almost no chance that the population extinct and that | + | In practice, there is almost no chance that the population will be extinct and that there is places where bacteria will develop indefinitely. |

If we want to be really sure, we just have to choose $N_0$ as | If we want to be really sure, we just have to choose $N_0$ as | ||

\[ N_0\geqslant\frac{3}{log_{10}\left(\frac{\lambda}{\mu}\right)} = \frac{3}{log_{10}\left(\frac{3,6 \times 10^{-2}}{4,6 \times 10^{-4}}\right)} = \frac{3}{log_{10}(78)} = \frac{3}{1,9} = 1,6 \] | \[ N_0\geqslant\frac{3}{log_{10}\left(\frac{\lambda}{\mu}\right)} = \frac{3}{log_{10}\left(\frac{3,6 \times 10^{-2}}{4,6 \times 10^{-4}}\right)} = \frac{3}{log_{10}(78)} = \frac{3}{1,9} = 1,6 \] | ||

| - | + | what, with our model, ensures us that if we deposit at least two bacteria on our lemon it will be wholly covered. | |

| Line 345: | Line 346: | ||

'''[https://2014.igem.org/Team:Paris_Saclay/Modeling/bacterial_Growth#Lax-Milgram_theorem_.24.5Cstar.5Cstar.24 [Mil]]''' D.R. Cox & H.D. Miller, ''The Theory of Stochastic Processes'', London : Methuen (1965) | '''[https://2014.igem.org/Team:Paris_Saclay/Modeling/bacterial_Growth#Lax-Milgram_theorem_.24.5Cstar.5Cstar.24 [Mil]]''' D.R. Cox & H.D. Miller, ''The Theory of Stochastic Processes'', London : Methuen (1965) | ||

| - | '''[Ren]''' Eric Renshaw, '' | + | '''[Ren]''' Eric Renshaw, ''Modeling Biological Populations in Space and Times'', Cambridge university press (1991). |

'''[https://2014.igem.org/Team:Paris_Saclay/Modeling/bacterial_Growth#General_conclusion_:_What_about_lemon_.3F [Ste]]''' Eric J. Stewart, ''Aging and Death in an Organism That Reproduces by Morphologically Symmetric Division'' on [http://www.plosbiology.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pbio.0030045 PLOS Biology] | '''[https://2014.igem.org/Team:Paris_Saclay/Modeling/bacterial_Growth#General_conclusion_:_What_about_lemon_.3F [Ste]]''' Eric J. Stewart, ''Aging and Death in an Organism That Reproduces by Morphologically Symmetric Division'' on [http://www.plosbiology.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pbio.0030045 PLOS Biology] | ||

{{Team:Paris_Saclay/default_footer}} | {{Team:Paris_Saclay/default_footer}} | ||

Latest revision as of 01:16, 18 October 2014

Contents |

Bacterial Population Growth

The oxygen diffusion model confirms the intuition we could have: while oxygen can't easily move into the medium, the growth on the surface is sufficiently more important than the growth inside the medium for neglecting the latter. We will tackle here the process of bacterial growth in different aspects.

We are here considering a bacterial population uniformly spread on a surface in the Euclidean space, in crowd-free conditions and with unlimited food resources.

In order to be as instructive as possible, we will process in two times : first we will consider that bacteria never die, then - and because the previous assumption is obviously not realistic - we will consider that bacteria can breed and die.

Each time, we will expose both a deterministic model and a stochastic one. The major advantage of the deterministic model is its simplicity. But this simplicity has a cost: while every set of variable states is uniquely determined by parameters in the model and by sets of previous states of these variables, the deterministic models perform the same way for a given set of initial conditions which is not really desirable. Conversely, in a stochastic model, randomness is present, and the variable states are not described by unique values, but rather by probability distributions.

Menu

Pure birth process

In this part, we assume that :

- bacteria do not die,

- they develop without interacting with each other,

- the birth rate, $\lambda$, is the same for all the bacteria, regardless of their age and does not change with time.

Deterministic model

Let $N(t)$ denote the population size at time $t$.

Then in the subsequent small time interval of length $h$ the increase in the population due to a single organism is $\lambda\times h$ - i.e the rate $\times$ the time - so the increase in size due to all $N(t)$ organisms is $\lambda\times h\times N(t)$. Thus \[ N(t+h) = N(t) + \lambda h N(t) +o(h) \] which on dividing both sides by h gives \[ \frac{N(t+h)-N(t)}{h} = \lambda N(t)+o(1) \] Let $h$ approach zero then yields the differential equation \[ \frac{dN}{dt}(t) = \lambda N(t) \] which integrates to give \[ N(t) = N_0 e^{\lambda t} \] where $N_0$ denotes the initial population size at time $t=0$. This form for $N(t)$ is known as the Malthusian expression for population development.It shows that these simple rules lead to exponential growth.

Stochastic model

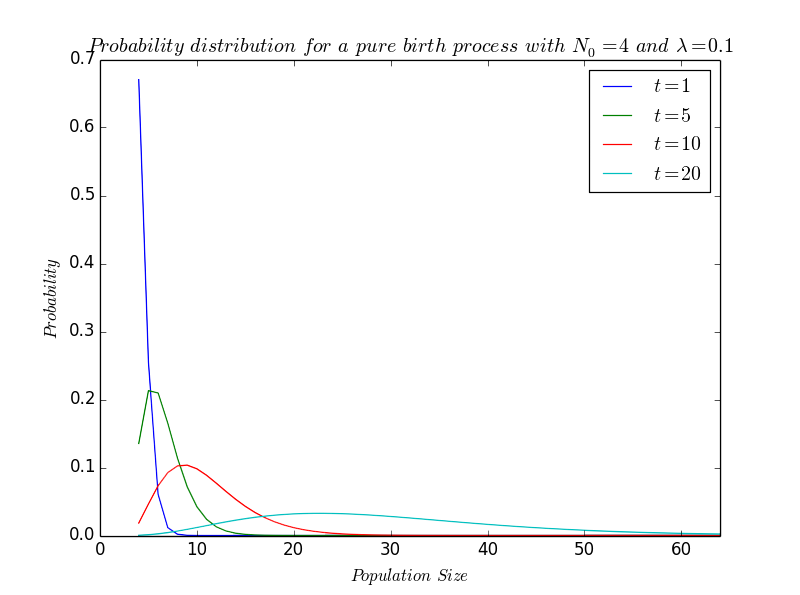

A deterministic model only gives us an average solution of the problem. In order to take into account the unpredictability of biology, we need a stochastic approach. Usually, the stochastic model converge to a limit which is similar to the deterministic model. A stochastic model is all the more pertinent as the initial bacterial population is small. It gives us an array of probabilities, that describes each possible state for the population at time t.

As in the deterministic model, we call $\lambda$ the birth rate : in a short time interval of length $h$ the probability that any particular cell will divide into two is $\lambda h$. Then for the population being of the size $N$ at the time $t+h$, either it is of the size $n$ at time $t$ and no birth occurs in the subsequent short interval $(t,t+h)$, or else it is of size $N-1$ at time $t$ and exactly one birth occurs in $(t,t+h)$. In fact, by choosing $h$ sufficiently small we may ensure that the probability of more than one birth occuring is negligible.

Since the probability of $N$ increasing to $N+1$ in $(t,t+h)$ is $\lambda h N$, it follows that the probability of no increase in $(t,t+h)$ is $1-\lambda h N$. Similarly, the probability of $N-1$ increasing to $N$ in $(t,t+h)$ is $\lambda(N-1)h$. Thus on denoting \[ p_N(t)(t) = \mathbb{P}(population~is~of~size~N~at~time~t) \] we have \[ p_N(t+h) = p_N(t)\times\mathbb{P}(no~birth~in~(t,t+h)) + p_{N-1}(t)\times\mathbb{P}(one~birth~in~(t,t+h))+o(h) \] i.e. \[ p_N(t+h) = p_N(t)\times(1-\lambda N h)+p_{N-1}(t)\times\lambda(N-1)h+o(h) \] On dividing both sides by $h$ \[ \frac{p_N(t+h)-p_N(t)}{h} = - \lambda N p_N(t)+\lambda(N-1)p_{N-1}(t)+o(1) \] and as it approaches zero this becomes \[ \frac{dp_N}{dt}(t) = \lambda(N-1)p_{N-1}(t)-\lambda p_N(t) \] for $N=N_0,~N_0+1,...$.

The solution of the above given equation is \[ p_N(t) = \left( \begin{array}{c} N-1 \\ N_0-1 \end{array} \right) e^{-\lambda N_0 t}(1-e^{-\lambda t})^{N-N_0} \quad;\quad N=N_0, N_0+1,... \] which is the negative binomial distribution where, for convenience, we have written $N(0)$ as $N_0$. In a practical way, this differential equation can be solved by a variety of theoretical techniques. While we are more interested here with the result than the mathematical formulae, we let the readers interested in the proof to consult Bailey's book The elements of stochastic processes [Bai], for instance.

As our solution is of the standard negative binomial form, the mean -i.e. the average value- and the variance -i.e. the average way that we move away from the mean- are given by : \[ m(t)=N_0e^{\lambda t}\quad and\quad V(t)=N_0e^{\lambda t}(e^{\lambda t}-1) \]

Especially, we see that the mean of the stochastic model is exactly what we have found by having a deterministic approach.

Simple birth-death process

In fact, the model we exposed in the previous part was not realistic and we have to consider that our bacteria could also die. We introduce here the death rate $\mu$ which is also supposed to be the same for all bacteria, regardless of their age and don't change with time. We still assume that bacteria develop without interacting with each other.

Deterministic model

We still have the same notation and $N(t)$ denotes the population size at time $t$.

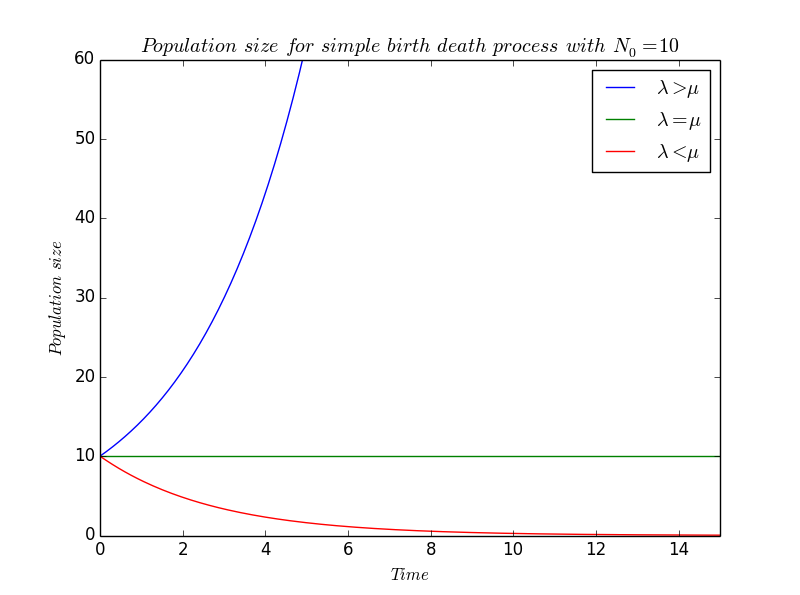

We proceed in a same way than in the pure birth process but, this time, death will lead to a decrease of the population, that's why the $\mu$ is preceded by a minus : \[ \frac{dN}{dt}(t) = (\lambda-\mu) N(t) \] which integrates to give \[ N(t) = N_0 e^{(\lambda-\mu) t} \] where $N_0$ denotes the initial population size at time $t=0$.

We still find an exponential growth, but the coefficient $(\lambda-\mu)$ can now be either positive or either negative in function of the values of $\lambda$ and $\mu$.

Stochastic model

Establishment of the model

Analysis of the stochastic behaviour follows exactly the same lines as for the pure birth process, except that in the short time $(t,t+h)$, there is now a probability $\lambda h$ that a particular bacterium gives birth and a probability $\mu h$ that it dies. With a population of size $N(t)$ at sime $t$, the probability that no events ocures is therefore $1-\lambda Nh-\mu Nh$, since $h$ is assumed to be sufficiently smal to ensure that the probability of more than one event occuring in $(t,t+h)$ is negligible.

As state $N$ can be reached from states $N-1$ (by a birth), $N+1$ (by a death) or $N$ (either), we find : \[ p_N(t+h) = p_N(t)\times(1-(\lambda+\mu)N h)+p_{N-1}(t)\times\lambda(N-1)h+p_{N+1}(t)\times\mu(N+1)h+o(h) \] Dividing by $h$ and letting $h$ approach zero then yields the set of equations \[ \left\{ \begin{array}{l} {\displaystyle \frac{dp_N}{dt}(t) = \lambda(N-1)p_{N-1}(t)-(\lambda+\mu)N p_N(t)+\mu(N+1)p_{N+1}(t)} \\ {\displaystyle p_N(0)=\delta_{N,N_0}} \end{array}\right. \] over $N=0,1,2\ldots$ and $t\geqslant0$ on which, for $N=0$, $p_{-1}(t)$ is identically zero.

Generating function $\star$

For the following part, the reader could refer to the book of Cox and Miller, The Theory of Stochastic Processes [Mil]. Let \[ \forall(z,t)\in\mathbb{R}^+*\times\mathbb{R}^+*,\quad G(z,t) = \sum_{n=0}^{\infty}p_n(t)z^n \] thus, $P_N(t)$ will be the coefficient before $z^N$ on $G(z,t)$. While $\forall t\in\mathbb{R}^+$, $p_N(t)\in[0,1]$ and we just consider the case of restricting $z$ to $\mathbb{R}^+*$ $G$ as a sence in $\overline{\mathbb{R}^+}~=~\mathbb{R}^+\cup\{+\infty\}$. We multiply the previous equation by $(z^0,z^1,z^2,\ldots)$ and add to obtain : \[ \begin{array}{rcl} {\displaystyle \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \frac{dp_n}{dt}(t) z^n} &=& {\displaystyle \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} (\lambda(n-1)p_{n-1}(t)-(\lambda+\mu)p_n(t)+\mu(n+1)p_{n+1}(t))z^n} \\ &=& {\displaystyle \lambda \sum_{n=0}^{\infty}p_{n-1}(t)(n-1)z^n - (\lambda+\mu)\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}p_n(t)nz^n + \mu\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}p_{n+1}(n+1)z^n} \end{array} \] and while we know that $p_{-1}=0$ \[ \begin{array}{rcl} {\displaystyle \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \frac{dp_n}{dt}(t) z^n} &=& {\displaystyle \lambda \sum_{n=0}^{\infty}p_{n}(t)(n)z^{n+1} - (\lambda+\mu)\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}p_n(t)nz^n + \mu\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}p_{n}(n)z^{n-1}} \\ &=& {\displaystyle \lambda z^2\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}p_{n}(t)(n)z^{n-1} - (\lambda+\mu)z\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}p_n(t)nz^{n-1} + \mu\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}p_{n}(n)z^{n-1}} \\ &=& {\displaystyle (\lambda z^2-(\lambda+\mu)z+\mu) \sum_{n=0}^{\infty}p_{n}(t)(z^n)'} \end{array} \] and finally \[ {\displaystyle \frac{\partial G}{\partial t}}(z,t) ~=~{\displaystyle (\lambda z^2-(\lambda+\mu)z+\mu)\frac{\partial G}{\partial z}(z,t)} ~=~{\displaystyle (\lambda z-\mu)(z-1)\frac{\partial G}{\partial z}(z,t)} \] which can be written as \[ \partial_tG(z,t)+f(z)\partial_zG(z,t) = 0\quad where\quad f(z) := -(\lambda z-\mu)(z-1) \]

Lax-Milgram theorem $\star\star$

We will try to apply the Lax-Milgram theorem in the following paragraph. Readers which are not familiar with the theory of distribution and how to use it in order to solve partial derivative equation (PDE) could consult the notes of N.Burq and P.Gerard Contrôle optimal des équations aux dérivees partielles [Bur].

As from now, we work in the space of distributions, $\mathcal{D}(\mathbb{R^2})$. Morever, we assume that the reader knows that $\mathbb{R}^+*\times\mathbb{R}^+*~\approx~\mathbb{R}^2$ -$\exp$ defines a bijection between $\mathbb{R}$ and $\mathbb{R}^+*$- and we will juste write $\mathbb{R}^2$ instead of $(\mathbb{R}^+*)^2)$. To all agree with the notation, we remind (or not) the definition of a Sobolev space. First we define \[ \mathcal{H}^1(\mathbb{R^2})=\{\phi\in\mathbb{L}_2(\mathbb{R^2})~|~\triangledown\phi\in\mathbb{L}_2(\mathbb{R}^2)\} \] In particular, we have \[ \mathcal{H}^1(\mathbb{R^2})\subset\mathcal{C}^{\infty}_0=\{\phi\in\mathcal{C}^\infty(\mathbb{R}^2)~|~Supp(\phi)~is~compact\} \] thus justify to set down \[ \mathcal{H}^1_0(\mathbb{R^2}) = \overline{\mathcal{C}^{\infty}_0(\mathbb{R}^2)}^{\mathcal{H}^1(\mathbb{R}^2)}\subseteq\mathcal{H}^1(\mathbb{R}^2) \] where $\overline{\ldots}^{\mathcal{H}^1}$ is a notation to say adherance in $\mathcal{H}^1$. $\mathcal{H}^1_0$ is an exemple of a Sobolev space. So, like the whole Sobolev space, it is an Hilbert space and we note $<~|~>$ his scalar product. \[ \forall u,v\in\mathcal{H}^1_0,\quad < u~|~v>~=~< u~|~v>_{\mathcal{H}^1_0}~:=~< u~|~v>_{\mathbb{L}^2}+< \triangledown u~|~\triangledown v>_{\mathbb{L}^2} \]

\[ \begin{array}{l} {\displaystyle \forall(z,t)\in\mathbb{R}^2,\quad\partial_tG(z,t)+f(z)\partial_zG(z,t) = 0\quad} \\ {\displaystyle \quad\quad\Leftrightarrow\quad\forall\phi\in\mathcal{C}^{\infty}_0(\mathbb{R}^2),\quad< \partial_tG+f\partial_zG~|~\phi> =0} \\ {\displaystyle \quad\quad\Leftrightarrow\quad\forall\phi\in\mathcal{C}^{\infty}_0(\mathbb{R}^2),\quad \int{\partial_tG\phi+f\partial_zG\phi} = 0} \\ {\displaystyle \quad\quad\Leftrightarrow\quad\forall\phi\in\mathcal{C}^{\infty}_0(\mathbb{R}^2),\quad a(G,\phi) = 0\quad where\quad a(G,\phi)=\int{\partial_tG\phi+f\partial_zG\phi}} \end{array} \]

Because of the linearity of the integral, $a$ is a bilinear form. So we just have to proof that $a$ is continue and coercive.

- $a$ is continue :

\[ \begin{array}{rcl} {\displaystyle |~a(u,\phi_n)~|=|~\int_{\mathbb{R}^2}{\partial_tu\phi_n+f\partial_zu\phi_n}~|} &=& {\displaystyle |~\int_{Supp(\phi_n)}{\partial_tu\phi_n+f\partial_zu\phi_n}~|} \\ &\leqslant& {\displaystyle \int_{Supp(\phi_n)}{|~\partial_tu\phi_n+f\partial_zu\phi_n~|}} \\ &\leqslant& {\displaystyle \int_{Supp(\phi_n)}{|~\phi_n~|.|~\partial_tu+f\partial_zu~|}} \end{array} \] The Cauchy-Schwar's inequality give us \[ \begin{array}{rcl} |~a(u,\phi_n)~|&\leqslant&\sqrt{ {\displaystyle\int_{Supp(\phi_n)}{|~\phi_n~|^2}}}\times\sqrt{{\displaystyle\int_{Supp(\phi_n)}{|~\partial_tu+f\partial_zu~|^2}}} \\ &\leqslant& ||\phi_n||_{\mathbb{L}_2}\times\sqrt{{\displaystyle\int_{Supp(\phi_n)}{|~\partial_tu+f\partial_zu~|^2}}} \end{array} \] Well, \[ \begin{array}{crl} |~\partial_tu+f\partial_zu~|&\leqslant&\max(1,\underset{x\in Supp(\phi_n)}\sup f(x)) |~\partial_tu+\partial_zu~| \\ |~\partial_tu+f\partial_zu~|^2&\leqslant&[\max(1,\underset{x\in Supp(\phi_n)}\sup f(x))]^2 |~\partial_tu+\partial_zu~|^2 \\ \int_{Supp(\phi_n)}{|~\partial_tu+f\partial_zu~|^2}&\leqslant&[\max(1,\underset{x\in Supp(\phi_n)}\sup f(x))]^2\int_{Supp(\phi_n)}{ |~\partial_tu+\partial_zu~|^2} \\ \sqrt{{\displaystyle\int_{Supp(\phi_n)}{|~\partial_tu+f\partial_zu~|^2}}}&\leqslant&[\max(1,\underset{x\in Supp(\phi_n)}\sup f(x))]\sqrt{{\displaystyle\int_{Supp(\phi_n)}{ |~\partial_tu+\partial_zu~|^2}}} \\ \sqrt{{\displaystyle\int_{Supp(\phi_n)}{|~\partial_tu+f\partial_zu~|^2}}}&\leqslant&[\max(1,\underset{x\in Supp(\phi_n)}\sup f(x))].||u||_{\mathbb{L}_2} \end{array} \] So \[ {\displaystyle |~a(u,\phi_n)~|\leqslant||\phi_n||_{\mathbb{L}_2}\times[\max(1,\underset{x\in Supp(\phi_n)}\sup f(x))].||u||_{\mathbb{L}_2}} \]

Let ${\displaystyle M=\underset{n\in\mathbb{N}}{\sup}\max(1,\underset{x\in Supp(\phi_n)}\sup f(x))}$. And the Heine theorem assure that $M$ is finit. Actually, $f$ is continue on the compact $Supp(\phi_n)$ for all $n$ in $\mathbb{N}$ so is bound on it. By passing to the limit, we find \[ {\displaystyle |~a(u,v)~|\leqslant (1+M)||u||_{\mathcal{H}^1_0}||\phi_n||_{\mathcal{H}^1_0}} \] which is what we were searching for.

- $a$ is coercive :

With a simular calculation, we show that $a$ is coercive, i.e. that it exists a constant $\alpha$ in such a way that \[ \forall u \in \mathcal{H}^1_0(\mathbb{R}^2), \quad |a(u,u)| \geqslant \alpha ||u||^2 \]

So, according to the Lax-Milgram theorem \[ \exists ! G\in\mathcal{H}^1_0,\quad\forall\phi\in\mathcal{H}^1_0,\quad a(G,\phi)=0 \] In other words, it means that, in the space of distributions, if we can exhibit a solution, it is the only solution of this problem. And the solution exists. If the solution we find is sufficiently regular (in a way to define more precisely), general theorems assure that the solution we find is not only a solution in the space of distributions but is also a solution in "the real life".

Precisely, we can verify with a computation that, if $\lambda\neq\mu$ \[ \gamma(z,t)~:=~\left(\frac{\mu(1-z)-(\mu-\lambda z)e^{-(\lambda-\mu)t}}{\lambda(1-z)-(\mu-\lambda z)e^{-(\lambda-\mu)t}}\right)^{N_0} \] is solution to the equation, i.e. that \[ \forall(z,t)\in\mathbb{R}^2, \partial t\gamma(z,t)+f(z,t)\partial z\gamma(z,t)=0 \] The computation is very long and not really interesting (it suffices to derive $\gamma$ and substitute in the equation) that's why we will not detail it in this text...

So, while the solution exists and is unique according to the Lax-Milgram theorem, if $\lambda\neq\mu$, we have found it and \[ \forall(z,t)\in\mathbb{R}^2,~G(z,t)~=~\left(\frac{\mu(1-z)-(\mu-\lambda z)e^{-(\lambda-\mu)t}}{\lambda(1-z)-(\mu-\lambda z)e^{-(\lambda-\mu)t}}\right)^{N_0} \quad(\star)\] and for all time $t$, $P_N(t)$ is the coefficient before $z^N$ in the previous expression.

Coefficient of Variation $\star\star$

In this small part, we will just try to have an idea of the influence of the value of $\lambda$ and $\mu$ on the probability. To do that, we calculate the mean and the variance of population size. Actually, while we consider a discrete probability, \[ m(t) = \sum_{n=0}^{\infty}{n p_n(t)} = \ldots = N_0 e^{(\lambda-\mu)t} \] and by a similar calcul, if $\lambda\neq\mu$, \[ V(t) = N_0\frac{\lambda+\mu}{\lambda-\mu}e^{(\lambda-\mu)t}(e^{(\lambda-\mu)t}-1) \]

Unlike $m(t)$, $V(t)$ depend not only on the difference between the birth and the death rates, but also on their absolute magnitudes. This is what we should expect, because predictions about the future size of a population will be less precise if birth and death occur in rapid succession than if they occur only occasionally.

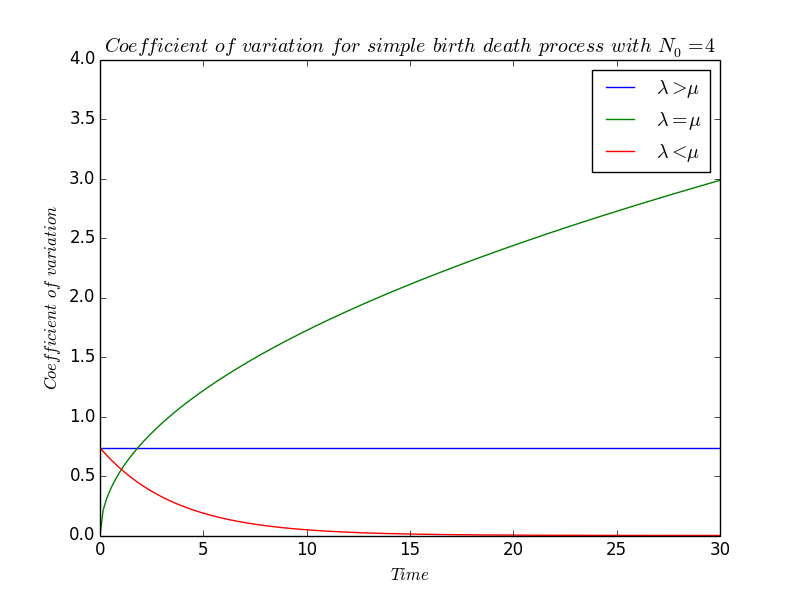

We define the coefficient of variation $\displaystyle CV(t)~:=~\frac{\sqrt{V(t)}}{m(t)}$ which qualify the variation of the system and we will study the effect of the relative values of $\lambda$ and $\mu$. \[ \begin{array}{rcl} \forall\lambda\neq\mu,~\forall t, CV(t) &=& {\displaystyle\sqrt{N_0\frac{\lambda+\mu}{\lambda-\mu}e^{(\lambda-\mu)t}(e^{(\lambda-\mu)t}-1)}\times\frac{1}{N_0}e^{-(\lambda-\mu)t}} \\ &=& {\displaystyle \sqrt{\frac{\lambda+\mu}{N_0(\lambda-\mu)}}\times\sqrt{e^{(\lambda-\mu)t}-1}\times e^{-\frac{1}{2}(\lambda-\mu)t}} \\ &=& {\displaystyle \sqrt{\frac{\lambda+\mu}{N_0(\lambda-\mu)}}\times\sqrt{e^{(\lambda-\mu)t}-1}\times \sqrt{e^{-(\lambda-\mu)t}}} \\ &=& {\displaystyle \sqrt{\frac{\lambda+\mu}{N_0(\lambda-\mu)}}\times \sqrt{1-e^{-(\lambda-\mu)t}}} \end{array} \]

- If $\lambda\gneq\mu$,

\[ CV(t)~\sim~\sqrt{\frac{\lambda+\mu}{N_0(\lambda-\mu)}} \]

- On the contrary, if $\lambda\lneq\mu$,

\[ CV(t)~\sim~\sqrt{\frac{\lambda+\mu}{N_0(\lambda-\mu)}}\times e^{\frac{1}{2}(\lambda-\mu)t} \]

- We are now interested in the coefficient of variation when $\lambda=\mu$. We cannot find an equivalent as easily as previously because $CV$, at least in that form , is not defined for $\lambda=\mu$. Actually, to know if $CV$ is defined or not when $\lambda=\mu$ is not really interesting because we want to have an idea of what will be the behaviour of $CV$ if $\lambda$ is so much close to $\mu$ that, biologically, they seem to be equal. It will be the same idea in the following part.

We remind that the function $\exp:x\rightarrow e^x$ is indefinitely differentiable, i.e. $\exp\in\mathcal{C}^{\infty}$ so it admits a Taylor expansion in the neighbourhood of $0$ -in particular- : $\forall n\in\mathbb{N}$ and for $t$ sufficiently near to $0$, \[ \begin{array}{rcl} e^t &=& {\displaystyle \exp(0)\frac{t^0}{0!}+\exp'(0)\frac{t^1}{1!}+\exp^{(2)}(0)\frac{t^2}{2!}+\exp^{(3)}\frac{t^3}{3!}+\ldots+\exp^{(n-1)}\frac{t^{n-1}}{(n-1)!}+\underset{t\rightarrow 0}{o}(t^n)} \\ &=& {\displaystyle 1+t+\frac{t^2}{2}+\frac{t^3}{6}+\ldots+\frac{t^{n-1}}{(n-1)!}+\underset{t\rightarrow 0}{o}(t^n)} \end{array} \] So, by developing the exponents in the expression of $CV$, \[ \forall t\in\mathbb{R},~CV(t) ~=~ \sqrt{\displaystyle{\frac{\lambda+\mu}{N_0(\lambda-\mu)}}}\times\sqrt{1-(1-(\lambda-\mu)t)} +\underset{\lambda\rightarrow\mu}{o}(\sqrt{(\lambda-\mu)t})\] and cancelling the expression, we find \[ CV(t)~=~\sqrt{{\displaystyle\frac{(\lambda+\mu)t)}{N_0}}} +\underset{\lambda\rightarrow\mu}{o}(\sqrt{t}) \] Finnaly, as $\lambda=\mu$, it comes that \[ CV(t)~\underset{\lambda\rightarrow\mu}\sim~\sqrt{{\displaystyle\frac{2\lambda t}{N_0}}} \]

At this point it is worth reflecting on a criticism sometimes levelled against this model of exponential population growth, namely that if $\lambda$ exceeds $\mu$ then it ultimately leads to so large populations that their existence is physically impossible.

A far more serious, but often neglected, question is How far into the future is ecological prediction, based on simple models, feasible ? The answer must depend on the situation being considered, since it is influenced to a large extent by biological factors such as over what length of time the (actual) birth and death rates can be expected to remain reasonably constant and how large $N(t)$ may become before organisms can no longer be assumed to develop independently of each other. Clearly, whenever a biological process is being modelled, no matter how innocently simple it may first appear, the underlying assumption used in the construction of the model must be constantly questioned. The feasibly and predictable future may be well quickly disapointing.

Probability of extinction $\star$

Last part but not least : we will study the probability of extinction of our bacteria population.

Intuitively, this probability will depend on $\lambda$ and $\mu$ : if $\lambda\ll\mu$, then it is reasonable to suppose that since death predominate the population will eventually die out, and since we have not considered immigration phenomenon, this implies extinction. On the contrary, if $\lambda\gg\mu$ then birth predominate. Either an initial downward surge leads to extinction of the population, or else $N(t)$ avoids becoming zero and the population grows indefinitely.

The probability that extinction occur at or before $t$ is the coefficient before $z^0$ in $(\star)$, i.e, \[ \left(\frac{\mu-\mu e^{-(\lambda-\mu)t}}{\lambda-\mu e^{-(\lambda-\mu)t}}\right)^{N_0} \] where $N_0$ still refer to $N(0)$.

In particular, this value for $N_0=1$ is the probability that a single bacterium and all his clones are extinct at or before time $t$.

To obtain the probability of ultimate extinction, $p_0(\infty)$, we have to let $t$ tend to infinity and

- If $\lambda\lneq\mu$,

\[ p_0(\infty)~\sim~\left(\frac{-\mu e^{\mu t}}{-\mu e^{\mu t}}\right)^{N_0}~=~1~\longrightarrow 1 \] Ultimate extinction is therefore certain.

- On the contrary, if $\lambda\gneq\mu$, then the exponential terms vanish, so

\[ p_0(\infty)~\sim~\left(\frac{\mu}{\lambda}\right)^{N_0}\longrightarrow\left(\frac{\mu}{\lambda}\right)^{N_0} \] In particular, even though $\lambda$ is greater than $\mu$, extinction can still occur. It must append when $N_0$ is small or when $\displaystyle \frac{\mu}{\lambda}$ is near one.

Thus, if we wish to choose $N_0$ to ensure that $p_0(\infty)\leqslant 10^{-3}$, then we require \[ \left(\frac{\lambda}{\mu}\right)^{N_0}\geqslant 10^3 \] i.e. \[ log_{10}\left(\left(\frac{\lambda}{\mu}\right)^{N_0}\right)~=~N_0 log_{10}\left(\frac{\lambda}{\mu}\right)\geqslant 3 \] and finally, \[ N_0\geqslant\frac{3}{log_{10}\left(\frac{\lambda}{\mu}\right)} \]

For example, if $\mu=1$ and \[ \lambda=1.01,\quad 2,\quad 10,\quad 100,\quad 1000, \] $No$ must be chosen such as \[ N_0\geqslant 695,\quad 73,\quad 10,\quad 3,\quad 2,\quad 1. \]

- It is a little bit more difficult to determine $p_0(\infty)$ when $\lambda=\mu$ because the expression $(\star\star)$ is not defined when $\lambda=\mu$. But, by reminding us that the exponential is $\mathcal{C}^\infty$ on $\mathbb{R}$ -particularly in $0$- and admit so a Taylor-expansion in the neighborhood of $0$ :

\[ e^t~=~1+t+\frac{t^2}{2}+\frac{t^3}{6}+\frac{t^4}{24}+\ldots+\underset{t\rightarrow 0}{o}(t^n) \] we can write $p_0$ as \[ p_0(t) = \left(\frac{{\displaystyle\mu-\mu(1-(\lambda-\mu)t+\underset{\lambda\rightarrow\mu}{o}((\lambda-\mu)t)}}{{\displaystyle\lambda-\mu(1-(\lambda-\mu)t+\underset{\lambda\rightarrow\mu}{o}((\lambda-\mu)t)}}\right)^{N_0} = \left(\frac{{\displaystyle \mu(\lambda-\mu)t+\mu\underset{\lambda\rightarrow\mu}{o}((\lambda-\mu)t)}}{{\displaystyle\lambda-\mu+\mu(\lambda-\mu)t+\mu\underset{\lambda\rightarrow\mu}{o}((\lambda-\mu)t)}}\right)^{N_0} \] This expression simplifies, by dividing by $\lambda-\mu$, to give \[ p_0(t) = \left(\frac{{\displaystyle \mu t+\underset{\lambda\rightarrow\mu}{o}(\mu t)}}{{\displaystyle 1+\mu t+\underset{\lambda\rightarrow\mu}{o}(\mu t)}}\right)^{N_0} \underset{\lambda\rightarrow\mu}{\sim}{\displaystyle\left(\frac{\mu t}{1+\mu t}\right)^{N_0}} \] As $t$ increases, \[ p_0(t)~\underset{\begin{array}{c}{\scriptstyle \lambda\rightarrow\mu} \\ {\scriptstyle t\rightarrow\infty}\end{array}}\sim~\left(\frac{\mu t}{\mu t}\right)^{N_0}~\underset{\begin{array}{c}{\scriptstyle \lambda\rightarrow\mu} \\ {\scriptstyle t\rightarrow\infty}\end{array}}\longrightarrow~1 \] and so ultimate extinction is certain even if the birth rate and the death rate are equal.

General conclusion : What about lemon?

To come back to our lemon porject, let's see what is appening when we consider now "our" own bacteria and not only a general bacterium species !

In practise, we use the genetically modified E.coli. As the modification that we carried out do not touch to the vital metabolism of bacteria we may assume that the original rates of birth and death for E.coli have not been changed.

So, according to researches of Eric Stewart [Ste], we have \[ \lambda = 3,6 \times 10^{-2} ~ min^{-1} \] and \[ \mu = 4,6 \times 10^{-4} min^{-1} \]

So we are in the case $\lambda>\mu$. The partition coefficient of variation ensure us that the system is asymptotically stable.

Moreover, we know, through the part probability of extinction, that the probability of extinction is, if we denote $N_0$ the initial population size,

\[ p_0(\infty) \sim \left(\frac{\mu}{\lambda}\right)^{N_0} = \left(\frac{4,6 \times 10^{-4}}{\lambda = 3,6 \times 10^{-2}}\right)^{N_0} \simeq (1.3 \times 10^{-2})^{N_0} \simeq 10^{-2~N_0} \]

which is really near to $0$.

In practice, there is almost no chance that the population will be extinct and that there is places where bacteria will develop indefinitely.

If we want to be really sure, we just have to choose $N_0$ as

\[ N_0\geqslant\frac{3}{log_{10}\left(\frac{\lambda}{\mu}\right)} = \frac{3}{log_{10}\left(\frac{3,6 \times 10^{-2}}{4,6 \times 10^{-4}}\right)} = \frac{3}{log_{10}(78)} = \frac{3}{1,9} = 1,6 \]

what, with our model, ensures us that if we deposit at least two bacteria on our lemon it will be wholly covered.

Actually, our model can be considerably improved but we feared it was not of the level of the iGEM competition.

References

[Bai] Norman T.J Bailey, The Elements of Stochastic Processes with Applications to the Natural Sciences, New York, Wiley (1964).

[Bur] Nicolas Burq & Patrick Gérard, Contrôle optimal des équations aux dérivées partielles, Ecole polytechnique (2002)

[Mil] D.R. Cox & H.D. Miller, The Theory of Stochastic Processes, London : Methuen (1965)

[Ren] Eric Renshaw, Modeling Biological Populations in Space and Times, Cambridge university press (1991).

[Ste] Eric J. Stewart, Aging and Death in an Organism That Reproduces by Morphologically Symmetric Division on [http://www.plosbiology.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pbio.0030045 PLOS Biology]

"

"