Team:Freiburg/Results/Modeling

From 2014.igem.org

Modeling

Introduction

The AcCELLerator has two major components: the light-regulated gene expression and the retroviral gene delivery. These two system are interconnected by the mCAT1, which acts as the receptor for MLV vectors and whose expression is regulated by the light system. The goal of modeling is describing the systems using mathematical language and trying to predict their behavior under any conditions. Since light-regulated gene expression and the retroviral gene delivery have been well studied and characterized, findings from previous research was adopted and modified to fit our experiments.

Our modeling was based on the combination of different differential equations. All functions were solved either analytically or numerically using MATLAB.

MLV Infection

Model Formulation

In our project, gene delivery was achieved by infecting the cells with the recombinant murine leukemia virus (MLV). As a typical retrovirus, its life cycle has been well characterized. Usually, this process can be divided artificially into several steps, including adsorption, internalization, integration, replication, assembly and release. However, our recombinant MLVs lacked the genes which are essentially for the replication and the virus assembly. Thus only the gene of interest (GOI), which is packed inside the viral RNA, could be integrated into the genome and expressed. The process from adsorption to integration can be again subdivided into seven steps (see Fig. 1), so that each step can be described with a simple mathematical model.

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of MLV infection

(1) The infection is initiated by the adsorption of the virions onto the cell surface, which is covered by the specific receptor mCAT1. (2) Once the virion binds with the receptor, fusion of viral and cell membrane is triggered and the viral core is internalized into the cytoplasm. (3) Using viral RNA as template, double stranded DNA is produced by reverse transcriptase. (4) The viral DNA is then transported along the microtubuli to the microtubule organizing center near the nucleus. (5) During the transcription and transport, the viral molecules could be degraded by cellular factors. (6) During cell division, the nuclear envelope dissolves and the viral DNA is imported into the nucleus. (7) Viral DNA is integrated into the chromosome by integrase. (modified from [1])

The whole infection process was described by a set of differential equations, which was adopted from previous works [1,2] with modifications.

First, a viral suspension of depth h was added to a layer of adherent cells to infect them (see Fig. 2). The concentration of the virion (Vm) is a function of both time and depth. It is influenced by four different factors: diffusion, sedimentation, degradation and binding.

Figure 2. Schematic diagram of the transduction procedure.

The virions (shown in yellow) build a gradient on the z-axis. Flux of virions is determined by four factors: diffusion along the concentration gradient, sedimentation due to gravity, degradation and binding to the receptor (shown in violett) on the adherent cells (shown in green).

The diffusion of the virions follows the fick’s law of diffusion. u is the velocity of sedimentation due to gravity. Since the virions are instable at 37°C, they decay in the medium with a constant decay rate kd_vm. Thus this additional term was added to the partial differential equation (PDE).

The diffusion coefficient Dv can be calculated according to the Stokes–Einstein equation,

and u was estimated as the Stokes settling velocity.

To solve the PDE, boundary conditions are required at the top and the bottom of the medium. At the top (z=h), net flux of virions has to be zero.

At the bottom (z=0), virions bind irreversibly onto the cell surface and are subsequently internalized. The binding rate is proportional to local virus concentration, cell density and density of mCAT1 receptor on the cell surface. Moreover, the binding is saturating at high receptor density, so a Michaelis-constant for receptor density was added to the equation.

Second, the MLV undergoes several steps (see Fig. 1 (3)-(7)) after the internalization to be integrated into the genome. However, it is difficult to determine the intracellular concentration of each viral component. The only output of our experiments was the transduction efficiency determined by flow cytometry. Thus it makes more sense to consider the dynamics between infected and non-infected cells.

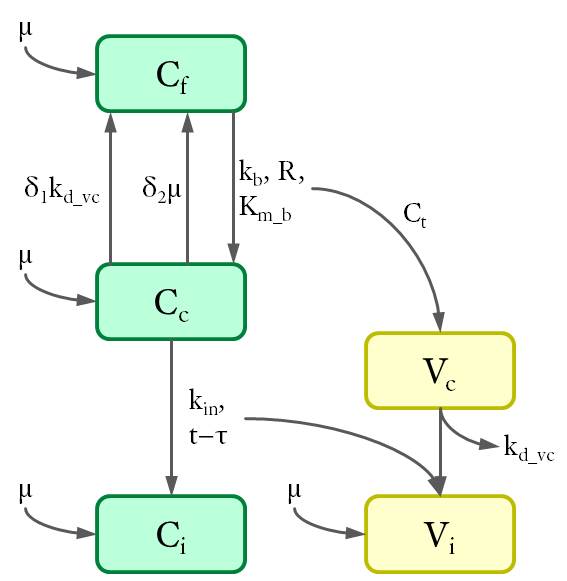

According to the location of intracellular viral particles, the cells were divided into three populations (see Fig. 3): virus-free cells (Cf), cells that carry MLV in the cytoplasm (Cc) and cells with viral DNA integrated in the genome (Ci). Similarly, intracellular viral particles were divided into cytoplasmic viruses (Vc) and integrated viruses (Vi). Particularly, a subpopulation of cytoplasmic virus inside the virus-carrying cells only (Vf) was also considered for further calculations.

Figure 3. Cell and virus populations and their density.

Cell populations (C) are shown in green and viruses (V) in yellow. The variables are defined as the density of each population (in 1/cm²) at the bottom of the petri dish.The dynamics between different cell and virus populations was influenced by several factors (see Fig. 4), including binding of new virions, intracellular degradation of viral particles with rate kd_vc, integration of viral DNA with integration rate kin, and cell division with a constant growth rate μ.

Figure 4. Dynamics of cell and virus populations.

Arrows towards and away from the rectangles describe the increase/decrease of the population with a specific rate indicated on the arrows, respectively.

Thus the differential equations were set up as follows.

δ1 is the possibility of a virus-carrying cell that becomes virus-free owing to the degradation of intracellular virus. Since multiple cytoplasmic viruses are unlikely to degrade at the same time, the possibility equals the fraction of virus-carrying cells with only one virus. Since the distribution of the multiplicities of infection (MOI) follows the poisson distribution[3], δ1 can be calculated using the following equation,

where the distribution is slightly modified to consider the virus-carrying cells only and nv is the average number of virus per cell inside these cells.

δ2 is the possibility of a virus-carrying cell that becomes virus-free during cell division. Because virus particles enter two daughter cells in a random process, one of them may lose all particles and became virus-free again. This possibility derived from the binomial distribution for a certain virus number. δ2 is the then the sum of products of poisson and binomial possibility for each MOI.

Besides, terms for the virus integration are calculated at time τ prior to the current time point t. τ is the mean trafficking time of the virus inside the cytoplasm and includes time for reverse transcription and viral transport (see Fig. 1 (3)-(4)). These terms turn these differential equations into a delay differential equation system (DDE), which was solved here by numerical methods.

The experimental output, the transduction efficiency, is defined as the fraction of virus-integrated cells.

Data Analysis

Extracellular virus degradation

The extracellular degradation rate of MLV (kd_vm) was first investigated. MLV suspension was incubated for different durations. The viral concentration should follow a single exponential decay function.

In our experiment, the virus suspension was transferred to the cells after the incubation and transduction efficiency was measured. The results were fitted to an exponential function to determine the degradation rate (see Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Extracellular degradation of MLV.

MLV vectors were incubated in cell-free medium at 37 °C for different durations and then infected NIH-3T3 cells for 72h. Transduction efficiency was measured by FACS. A single exponential function was fitted to the data (shown in line).

The extracellular degradation rate was about 0.124 h-1 and the half-life of MLV equals 5.6 h. This result is consistent with that obtained by Tayi et al. and shows the instability of the retroviral vector at physiological temperature in extracellular conditions.

Estimation of viral titer

Due to limited time, we did not carry out all experiments to determine every parameter. Thus the remaining parameters including binding, intracellular degradation, integration rate and trafficking time were adopted from Tayi’s paper. By means of this model with the parameter, we estimated the viral titer of our MLV suspension.

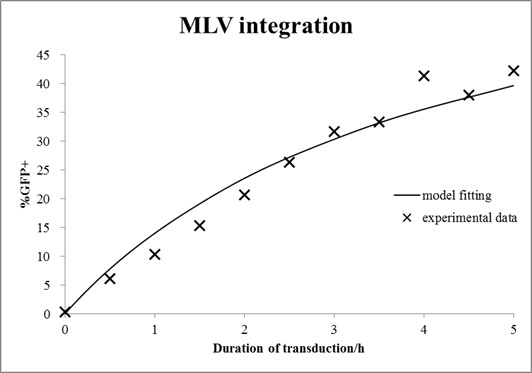

In this case, mouse cells were infected by MLV for different durations and then incubated in virus-free medium for a certain time. The equations with an unknown virus concentration were solved and fitted to the experimental data using least square estimation (see Fig. 6).

Figure 6. Estimation of virus titer.

Mouse cells were incubated with MLV for different durations and then washed with medium. After 72 h of growth, cells were analyzed by FACS. The mathematical model with an unknown viral titer was fitted to the data by least square estimation (shown in line).

The estimated virus titer is 1.2∙107 vectors/ml. This value is typical for standard protocols with helper-free retroviral production.[4]

Verification of virus titer

The estimated virus titer was verified by predicting the transduction efficiency with virus dilution and comparing it with the experimental data. MLV stock was diluted with a factor 0.1 to 0.5 and incubated with mouse cells. Transduction efficiency measured at the end of the experiments was shown in Fig. 7 as well as the prediction from our model.

Figure 7. Verification of virus titer.

MLV suspension was diluted by different factors and added to the NIH-3T3 cells and incubated for 48 h. The viral titre estimated in the last experiments was used to predict the transduction efficiency (shown in line).

The prediction was consistent with the data. The result demonstrates that our model is a good simulation of the infection process and can be applied for further experiments.

Light System

Model Formulation

The light system regulates the expression of the mCAT1, enabling the spatio-temporal control of virus-targeting. Modeling of the light system is based on ordinary differential equations (ODE). Fig. 8 shows the three major components of the system that are essential for the model: the activator ePDZ-VP16, the mRNA of mCAT1 and the mCAT1 protein on the plasma membrane (R: receptor).

Figure 8. The blue light system

The dashed lines indicate regulation by another component and the solid lines indicate changes with a certain rate. l is defined as the light condition and equals 1/0 when light is on/off, respectively.

First of all, genes for the light system are introduced into the cells by transfection. The plasmid is not able to self-replicate inside mammalian cells, so the average plasmid concentration decreases during cell division. It is necessary to consider this dilution factor, the gene dosis (GD), which reduces exponentially with the growth rate of the cells.

The key element in the blue light system is the ePDZ-VP16 fusion protein, which interacts with the light-sensitive LOV2 protein and activates the transcription. After the transfection, expression and degradation of ePDZ-VP16 reaches an equilibrium. The concentration of ePDZ-VP16 and thus the rate of activation is proportional to the plasmid concentration. In addition, the mCAT1 gene has a basic transcription rate which is also proportional to the plasmid concentration. Rate of transcription is their sum if the light is on, i.e. if the light condition l=1. Thus the transcription of mCAT1 RNA can be described as follows,

The mRNA is then translated into mCAT1 protein.

Data Analysis

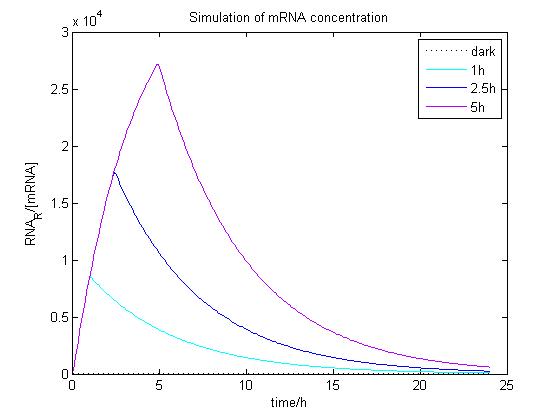

The ODE of the blue light system were solved analytically under different conditions with arbitrary parameter values to simulate the properties of light-regulation. mRNA concentration and receptor density of mCAT1 were calculated with the transfected cells kept in dark or illuminated for different durations (see Fig. 9 and 10).

Figure 9. Simulation of mRNA concentration at different conditions.

Arbitrary parameter values were used for simulation. Transfected cells were illuminated with blue light for 0 (dark), 1, 2.5 or 5 h and incubated 24 h.

Figure 10. Simulation of receptor density at different conditions.

Arbitrary parameter values were used for simulation. Transfected cells were illuminated with blue light for 0 (dark), 1, 2.5 or 5 h and incubated 24 h.

For comparison, the blue light system with the SEAP gene was transfected into HEK-293T cells and the production of SEAP was assayed at different illumination conditions (see Fig. 11).

Figure 11. SEAP production after different times of blue light illumination.

Cells were transfected with the blue light system including the SEAP reporter, illuminated with blue light for 0 (dark), 1, 2.5 or 5 h and incubated for 24 h. SEAP concentration was measured.

The data was insufficient for model fitting and determination of the parameters. However, it indicates a similar trend with the simulation: longer illumination time leads to a larger amount of GOI expression. But longer illumination with the energy-rich blue light may be harmful for the cells. The toxicity of light should be considered in the model for future improvements. Further experiments are required to determine the parameters and the optimal illumination time.

References

- Tayi, V. S., Bowen, B. D., & Piret, J. M. (2010). Mathematical model of the rate‐limiting steps for retrovirus‐mediated gene transfer into mammalian cells. Biotechnology and bioengineering, 105(1), 195-209.

- Kwon, Y. J., Hung, G., Anderson, W. F., Peng, C. A., & Yu, H. (2003). Determination of infectious retrovirus concentration from colony-forming assay with quantitative analysis. Journal of virology, 77(10), 5712-5720.

- Fields, B. N., Knipe, D. M., & Howley, P. M. (2007). Fields virology. 5th.

- Pear W S, Nolan G P, Scott M L, et al. Production of high-titer helper-free retroviruses by transient transfection[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 1993, 90(18): 8392-8396.

"

"