Before we get started:

Biofilm formation is part of the reason S. mutans is so devastating to oral health (see [Project Overview] for more information). For adequate oral protection, biofilm formation is a problem we must solve, and we can do so externally, via our probiotic (see [Cleanse: Antibiofilm]), or internally, by altering the genome of S. mutans. This means we need a way to silence the appropriate proteins.

So how are proteins silenced? As we know, proteins are translated from single-stranded mRNAs. Just like eukaryotic cells, bacteria can selectively silence mRNA by transcribing sequences of sRNA, or bacterial small RNA.

These small RNA molecules are usually less than 50bp long, and function by binding to the specified, complementary mRNA strand to prevent ribosome attachment. We decided that targeted sRNA would give us a good shot at silencing proteins in S. mutans.[1]

Next up, we need to find some proteins to silence!

So how did we do it?

After careful literature search, we found two candidates:

Histidine kinase 11 (HK11) is a sensor kinase from a two-component signal transduction system. Literature indicates that a knock-out of HK11 resulted in dramatically decreased biofilm formation.[2]

G protein in S. mutans (SGP) is involved in the regulation of intracellular GTP/GDP ratio, response to stress, and other diverse cellular functions. As with HK11, a knock-out of SGP resulted in dramatically decreased biofilm density.[3][4][5]

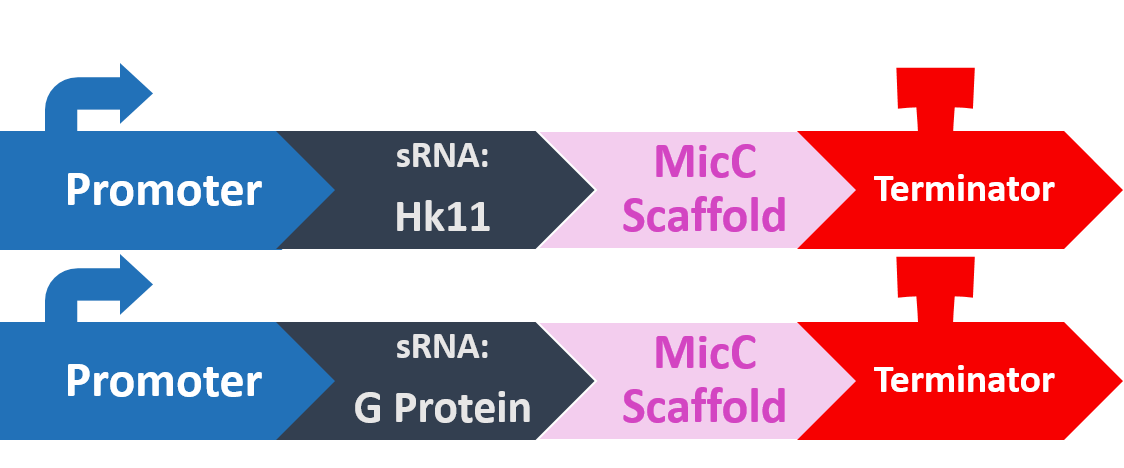

In order to silence these two proteins with sRNA, we synthesized a 24bp strand of non-coding DNA, and transcribed it into the corresponding RNA. This small RNA sequence is our artificial sRNA, and will bind to the TIR (translation initiation region) of our target mRNAs. This prevents the target mRNA from undergoing translation.

The final thing we need is something to help smooth out the whole process. The MicC scaffold is a specially constructed sequence which recruits the Hfq protein. The Hfq protein then helps our sRNA hybridize with its target mRNA, while stabilizing the sRNA-mRNA complex. Note that, since we want the products in RNA form, we also do not need an RBS (ribosome binding site).

At last, our circuit is complete!

Here is what our product would look like:

As mentioned, the sRNA part would bind to the TIR of the target mRNA, while the MicC scaffold recruits the Hfq protein to stabilize the entire structure.

Putting it to the test!

Having a circuit is only the start! Now we must test how well our circuits function. For the sRNA protein-inhibition module, a crucial test is of course how well the system performs, which is measured by the biofilm formation before and after transformation.

Does sRNA silencing work?

To test our sRNA function, we first cultured S. mutans so they have a chance to form a layer of biofilm. After biofilm is formed, we discarded the supernatant, and stained with a histological stain called Crystal Violet (CV). CV was used primarily to distinguish between Gram bacteria types, and have a strong affinity to biofilms, whose composition contains similarities with cell walls. After drying the sample and removing excess stain, we dissolved the biofilm and measured OD, to determine the amount of biofilm that has formed.

Theoretically, if our sRNA silencing works, we should see less biofilm (and less CV) when compared to the wild type.

Here is the details of our method:

Quantitative Growth of Biofilms on Microtiter Plates[7]

- Prepare overnight cultures in BHI broth and incubate at 37°C.

- Add 100 μL of the overnight culture to 5 mL BHI medium and incubate at 37°C until optical density at OD600 0.5. Chill on ice until all the culture reached the desired OD600.

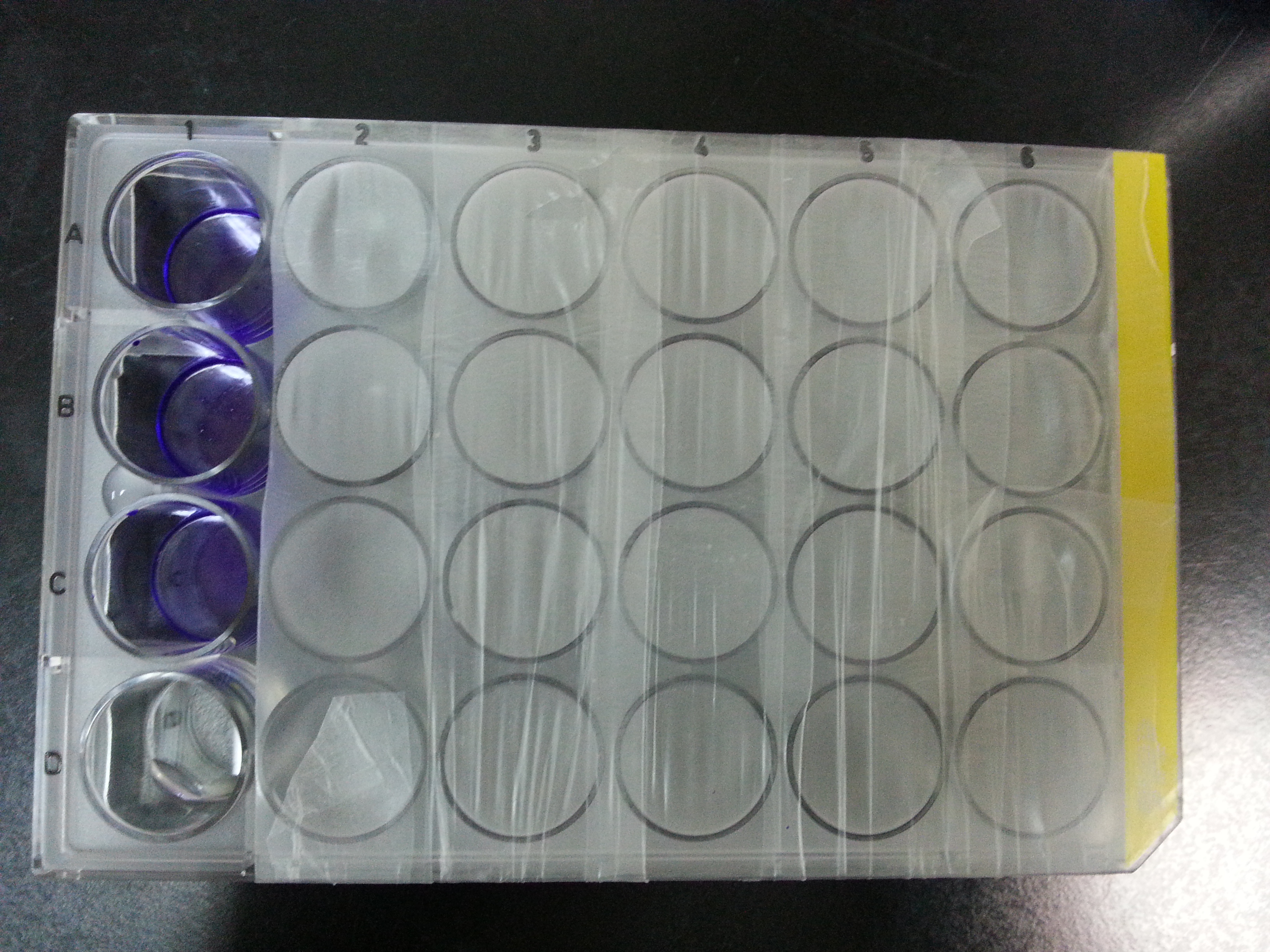

- pre-warm BM medium at 37°C for 1 h. (see figure 1.)

- Dilute cultures 1:100 in BM medium.Dispense 200 μL of each diluted culture into three wells. Wells containing uninoculated BM medium should serve as negative controls.

- Incubate plate for 24 h at 37°C without agitation.

- Blot the plate on a paper towel to remove culture media. To remove loosely bound cells, carefully immerse the 96well plate in a box with distilled water. Blot the plate on a paper towel. Repeat this step twice.

- Add 50 μL of 0.1% crystal violet to the test wells, including the negative control wells. Incubate for 15 min..

- Repeat step 6.

- Air dry plate and photograph. (see figure 2.)

- Add 200 μL of 95% ethanol to the wells. Leave for 10 min. Keep the plate covered. Transfer the ethanol to a 1 mL cuvette.

- Bring the volume of all cuvettes to 1 mL using Milli-Q water (including controls) and mix well.

- For biofilm growth, read at a wavelength of OD600. Blank with a cuvette containing the solution from a crystal violet-stained uninoculated well.

Figure 1. BM medium and the components stock. (more detail in [7] p.2)

Figure 2. 24 well plate after CV staining. First row is wild type S. mutans, Second is modified HK11, third is modified SGP, the last is uninoculated BM.

Our results

We have sent our circuit to sequence it, all of the sequence is correct.

After 25.5hr incubating, un-inoculated BM is served as blank and measuring OD600.

| well 1 | well 2 | well 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 1.651 | 1.913 | 2.014 |

| modified HK11 | 0.217 | 0.166 | 0.154 |

| modified SGP | 0.121 | 0.383 | 0.123 |

After 40hr incubating, uninoculated BM is served as blank and measuring OD600.

| well 1 | well 2 | well 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 1.63 | 1.64 | 1.678 |

| modified HK11 | 0.48 | 0.625 | 0.71 |

| modified SGP | 1.268 | 1.314 | 1.437 |

This result show that our sRNA mechanism is very successful. Although the biofilm quantity of modified SGP after 40hr incubating is higher than 20hr incubation, it may result from biofilm degradation (according to a professor who specializes in the study of biofilm).The data show that modifiedS. mutansbiofilm formation has been decreased dramatically. To prove that there is not a great difference between the growth rates of modifiedS. mutansand wild type S. mutans, we have ploted the growth curve of modifiedS. mutans.

There is no great difference between wild type and modified S. mutans, so we can conclude that sRNA is functioned in our modified S. mutans

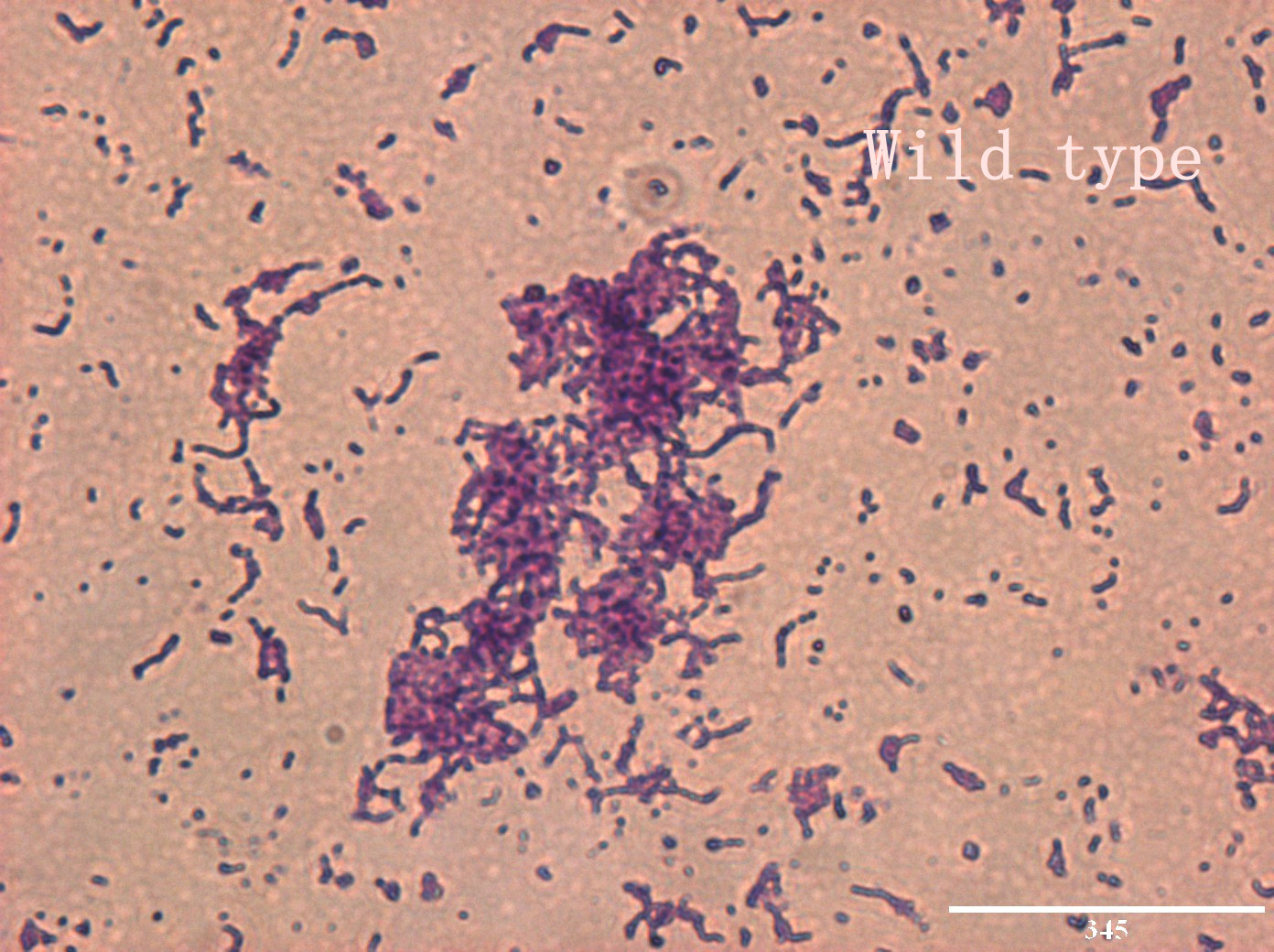

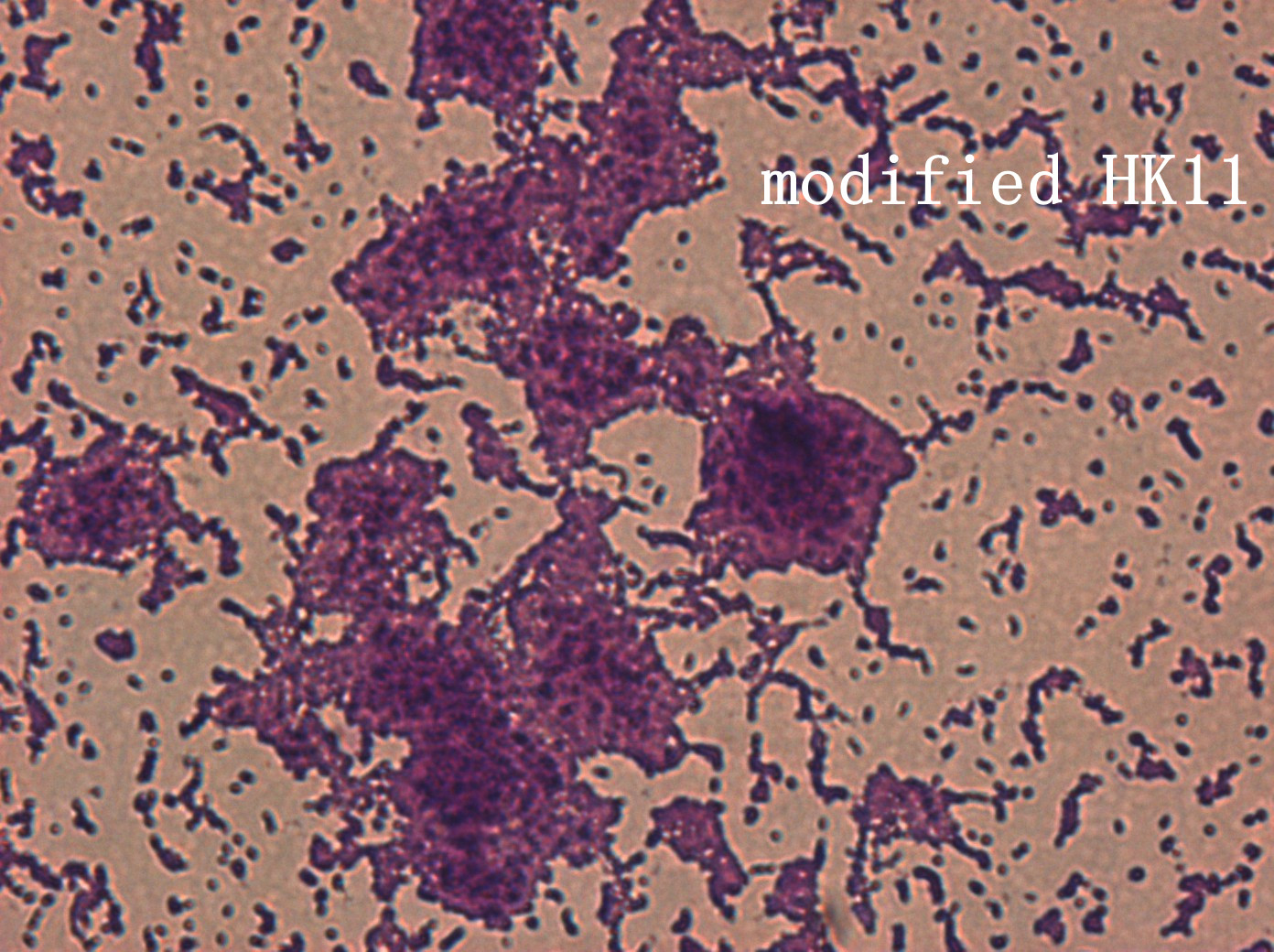

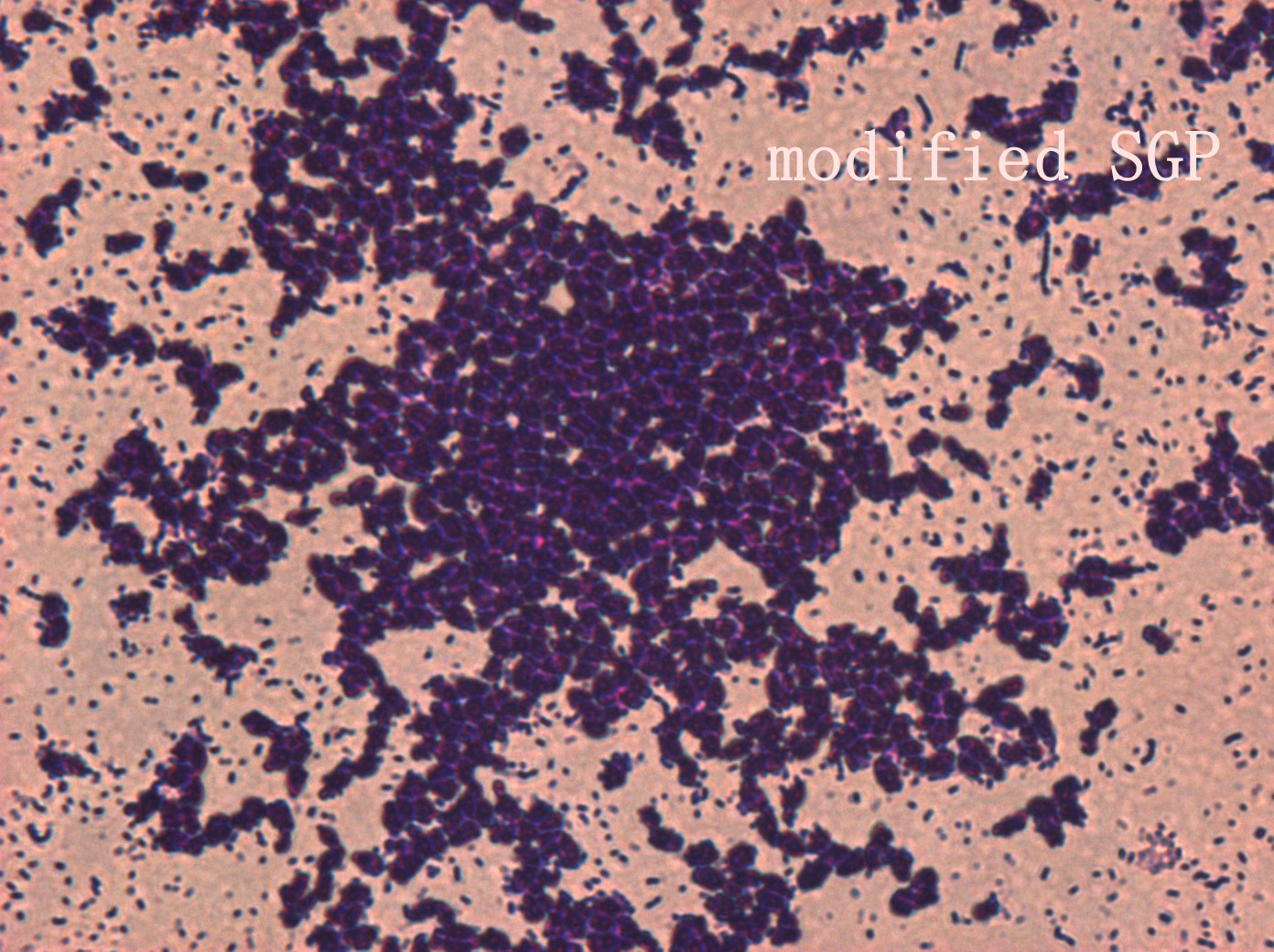

In addition, we culture the S. mutans on the silde glass coated saliva for 2 days to observe staining biofilm under microscope. We expect to see modified S. mutans will have sponge-like and looser architecture.

The pictures are 400X wild type, modified HK11, modified SGP S. mutans under microscope. The modified SGP is apparently different from wild type in appearance, though the biofilm is invisible under light microscopy, we still couldn’t deny the probability that this antisense strain could lead to destruction of biofilm formation.

In the future, we are going to use confocal microscope or scanning electron microscope that can directly observe biofilm to support our experiment.

"

"