Team:Heidelberg/Project/LOV

From 2014.igem.org

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{:Team:Heidelberg/templates/wikipage_new| | {{:Team:Heidelberg/templates/wikipage_new| | ||

| - | title= | + | title=LOV domain |

| | | | ||

white=true | white=true | ||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

header-bg=black | header-bg=black | ||

| | | | ||

| - | subtitle= | + | subtitle= Trying to photocontrol intein splicing |

| | | | ||

container-style=background-color:white; | container-style=background-color:white; | ||

| Line 22: | Line 22: | ||

content= | content= | ||

<div class="col-lg-12"> | <div class="col-lg-12"> | ||

| - | {{:Team:Heidelberg/pages | + | {{:Team:Heidelberg/pages/LOV}} |

</div> | </div> | ||

| | | | ||

Revision as of 00:36, 16 October 2014

– Trying to photocontrol intein splicing

ABSTRACT

...

Contents |

Introduction

Protein splicing allows for the introduction of major changes to a proteins sequence and structure even after translation. Although this mechanism alone offers a huge amount of possible applications highlighted in our toolbox, it would be advantageous to have control over the time and location of the splicing reaction especially for in vivo applications. However, the fact that inteins are attached to the protein they splice off from makes induction in whatever way rather difficult.

Controlling Inteins

Different ways exist for controlling the intein splicing reaction. In the literature this is mostly referred to as conditional trans splicing (CTS) or conditional protein splicing (CPS). The oldest method of inducing protein splicing is to chemically control the activity of inteins by changing the pH or redox state of their environment. This has been achieved for a multitude of inteins such as Ssp DnaB [1] or Mtu recA [2]. Yet the major drawback is obvious: These methods are only effectively applicable in vitro and usually depend on complexly purified reagents.

Within the past decades, more advanced systems were designed involving the binding of different ligands or the fusion of inteins to various protein domains. For example Mootz et al. succeeded in inhibiting the splicing reaction of an synthetically engineered version of Ssp DnaE through the addition of rapamycin [3]. Similarly, the S. cerevisiae VMA intein has been conditionally activated by rapamycin induced complementation of FKBP and FRB protein domains. There have previously been attempts to light induce inteins with an analogous system in which the VMA intein halves are fused to the chromoproteins Phytochrome B (PhyB) and Phytochrome Associated Factor 3 (PIF3) [4]. Upon light induction at 660 λ nm PhyB and PIF3 assemble bringing the intein halves together to initiate splicing. Although most certainly a useful tool, these principle can only work for inteins with low affinity to each other and therefore with rather low reaction rates. When using faster inteins, the corresponding halves bind to each other with significantly higher affinity and thereby start the splicing reaction independently from the binding state of their coupled protein domains.

We therefore came up with a new method to inhibit an intein's function light-dependently using LOV2 domain photocaging.

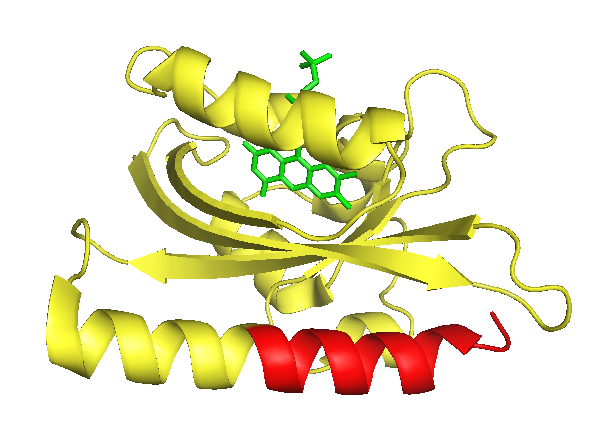

The As LOV2 domain

As LOV2 is the second Light-Oxygen-Voltage domain from the Avena sativa phototropin 1 (Figure 1). In its host organism, the common oat, phototropin 1 is a blue-light receptor involved in the response of growth to environmental light conditions and may be responsible for the opening of stomata and the movement of chloroplasts [5]. LOV2 mainly consists of a flavin mononucleotide (FNM) -binding core containing a FNM as chromophore, as well as a helical structure on the C-terminus, the J-alpha helix. Upon excitation with light, a cysteine within the core covalently binds the activated FMN, which induces a conformational change resulting in the protrusion of the formerly concealed J-alpha helix [6].

This light dependent change in conformation can be used to control cellular processes via light induction, a method for which two strategies exist: It has been shown, that proteins or protein domains which are fused C-terminally to the LOV2 are not able to bind to possible interaction partner due to sterical hindrance. Only after the conformational change initiated by illumination the J alpha helix is exposed, and so is the attached protein domain and its catalytic core. [7]. Instead of being fused to the very end, small amino acid sequences can be introduced and therefore hidden within the J alpha helix. Usually, this offers a better light-state to dark-state (signal to noise) ratio. This approach, also termed photocaging, has already been used to control degradation or nuclear accumulation of proteins [8][9].

As in LOV photocaging inhibition is not achieved by merely blocking an active centre but by completely hiding the whole binding partner we assessed the latter strategy as the most promising. Because of the C-terminal location of the J-alpha helix, the place that photocaging takes place in, an intein that is hidden within the LOV domain and splices off a fused protein without creating a significant scar needs to be a C-intein. It has been suggested that the length of the caged peptide itself determines the success of the photo caging [10]. Thus, we extensively screened the literature and discovered a set of only six amino acids long C–inteins.

S11 split inteins

Interestingly, there seem to exist only very few inteins with small C-terminal halves. The shortest and therefore most suitable were the S11 split inteins, engineered and thoroughly, but solely described by Lin et al. [11] . S11 inteins are engineered from mini-inteins, meaning that, unlike most other inteins, they do not have an internal homing endonuclease domain. Naturally, they are not trans-, but cis-splicing inteins and their crystal structure reveals twelve β-strands. To gain very small C-terminal split inteins, they were artificially separated between the 11th and 12th β-strand resulting in a 120-160 aa N- and 6 aa C-intein. We decided to use the Ssp DnaX, Ssp GyrB and Ter DnaE3 inteins since there properties were promising i.e. they showed the highest splicing activity.

Cloning and Methods

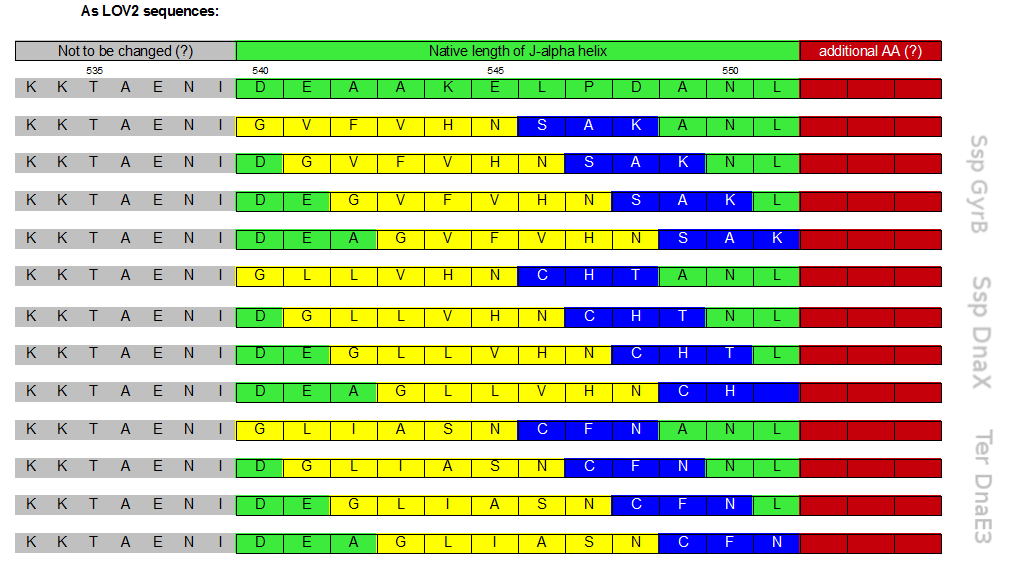

Rational Design of inLOV constructs

Initially a screening for the caging of three different S11- inteins, namely SspDnaX, SspGyrB and TerDnaE-3, at various positions within the J-alpha helix of the LOV domain was planned (Figure 2). The best split fluorescent protein was thought to provide an easy read-out for the best combination of caging position and C-terminal split intein. Unfortunately, we encountered many problems: the assembly construct with two insertion sides in which the LOV domain ought to be embedded for an easy exchange of caging positions via golden gate cloning was not ready at this time point. Secondly, a screening for the best split fluorescent protein turned out to be more time intensiv than expected.

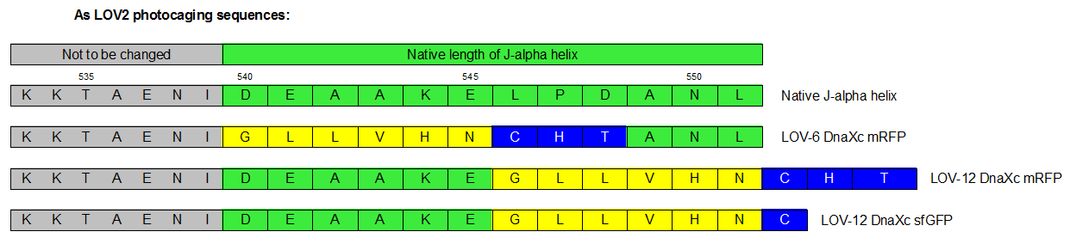

Therefore we designed a fast track cloning strategy with solely two caging positions of one intein in the alpha-helix and two split fluorescent proteins(Figure 3). In case of the S11- inteins, we chose SspDnaX, since they it was described as the most efficient C-terminal S11 intein [11]. Previous studies showed that the amino acid sequence of the J-alpha helix in front of the isoleucine at position 539 (I539) should not be changed, in order to preserve its reactivity to light [10]. However the sequence following I539 can be adapted to small peptide sequence. We caged SspDnaX at the two most extreme positions, believing that those would result in the greatest differences in caging efficiency. The LOV - 12 mutant represents the caging of SspDnaX right after I539, resulting in the deletion of all remaining amino acids (-12) of the J-alpha helix. In the mutant LOV - 6, the short C - intein occupies the SspDnaX at the very end of the helix, resulting in the deletion of only 6 original amino acids (Figure 4).

In our sfGFP reconstitution assay, we already established an approach to easily read-out the intein splicing reaction. However in this assay we used the NpuDnaE inteins, which were known to splice even with unnatural exteins as far as the cysteine of the C-terminal extein is present. Therefore we obtained only this one amino acid scar in the spliced product, which can be crucial for the restoration of fluorescence in front of the chromophore region (65-67). It is not known if same assumptions can be made for SspDnax. To test this, we chose one LOV mutant using the sfGFP as split fluorescent protein with only one extein flanking the intein (figure 4, mutant 3). To provide a backup if SspDnaX does not splice with only one extein, we also designed two LOV mutants with split mRFP. In the case of mRFP, we decided for split position 168/169, since this position was already successfully demonstrated in bimolecular fluorescence complementation [12]. The split position is located between β – barrel 8 and 9, which provides enough space for larger insertions.

Cloning strategy

The three LOV mutants, namely LOV-12 SspDnaX-sfGFP, LOV-12SspDnaX-mRFP and LOV-6SspDnaX-mRFP, were created via a fast track cloning strategy using CPEC. Employing the same method, constructs were generated that do not contain the LOV domain. Both, controls that should be able to conduct the splicing reaction and controls that contain mutated intein residues at the splicing side preventing the splicing reaction were produced. Subsequently the C - terminal SspDnaX containing the LOV domain and the N-terminal construct were cloned in bisctronic expression backbone using standard biobrick cloning.

Measurement of reconstituted fluorescent protein

We transformed all constructs in BL21(DE3) to allow expression under the T7 promoter. 5ml cultures were inoculated with 500 µl of an overnight culture and induced with 1mM as soon as the cultures reached the OD600 of 0.8. The cultures were incubated at 37 °C for further 1-2 hours. Subsequently, the cultures were left on room temperature as it is described in the paper that originally describes the S11 inteins [11]. Simultaneously all cultures were portioned and distributed on a 24 well plate and either illuminated with blue light of 470 nm for 30 min to 12 hours or kept in the dark for the same period of time. All samples were irradiated to either allow the conformational change of the LOV domain or prove the invulnerability against phototoxicity. The fluorescence was measured with the FACS using an excitation wavelength of 488 nm and emission spectra of 497 to 522 nm for sfGFP and excitation wavelength 561 nm with an emission spectra of 602 to 662 nm for mRFP. The samples were diluted 1:1000 and every FACS run analyzed 100000 events. To validate our results we conducted several assays with a series of biological replicates following the same experimental layout. For the Western Blot, cells were harvested by centrifugation for 5 min at 8000 rpm at 4 °C. The supernatant was discarded and the pellet frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at 4 °C. After collecting all samples of each time point, the pellet was re-suspended in 50 µl Laemmli-Buffer and heated at 95°C for 10 minutes. The samples were once again centrifuged and 2 µl of the supernatant was diluted with 10 µl Lämmli-Buffer. 6µl of each dilution was loaded on the SDS-PAGE, either stained via Coomassie solution or visualized in the Western Blot.

Results

During the planning phase two preparatory experiments were run to test the conditions for light induction: Please visit conditions testing to read more about the procedures and results.

The previous idea to set up a quick Flow Cytometry assay for screening LOV photocaging mutants had to be slightly adapted due to lack of time. However, to truly confirm protein splicing SDS-PAGE and Western Blot is the more reliable and definite method. We therefore present these results first.

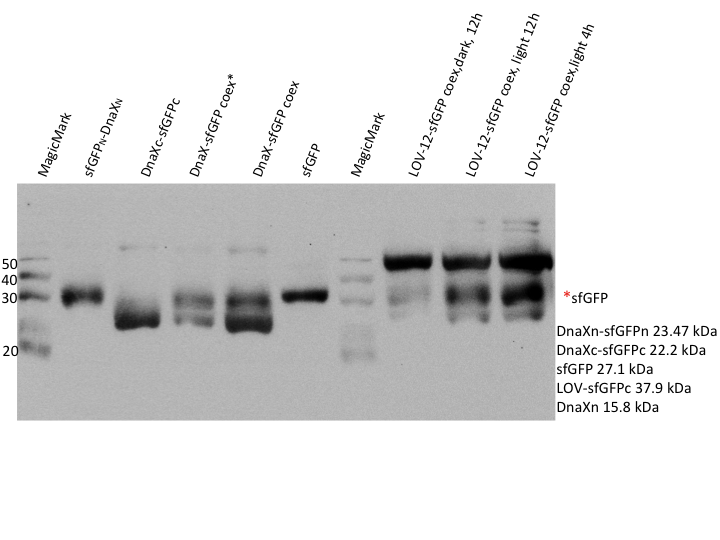

PVDF membranes were analysed with hexahistidine-antibody. The western blot confirms the expression of all his-tagged constructs, i.e. the mRFP and sfGFP N- and C-terminal halves with their corresponding intein, mRFP and sfGFP coexpression, sfGFP_T65C positive control and the LOV-6 and -12 constructs. The mRFP positive controls are not visible on the anti-His6 blot as they do not include a his-tag.

For superfolder GFP no intein splicing is shown (Figure 4). In the individually expressed as well as in the coexpressed samples the bands for sfGFPn-DnaXn and DnaXc-sfGFPc are clearly visible at ~23.5 kDa and 22 kDa, respectively. However, in the coexpressed splicing and coexpressed non-splicing samples no band at the expected size of ~27 kDa exists for sfGFP. The evaluation was complicated by the fact that native-sized superfolder GFP runs only little below the size of the N-terminal construct. An additional western blot was therefore performed with GFP antibody.

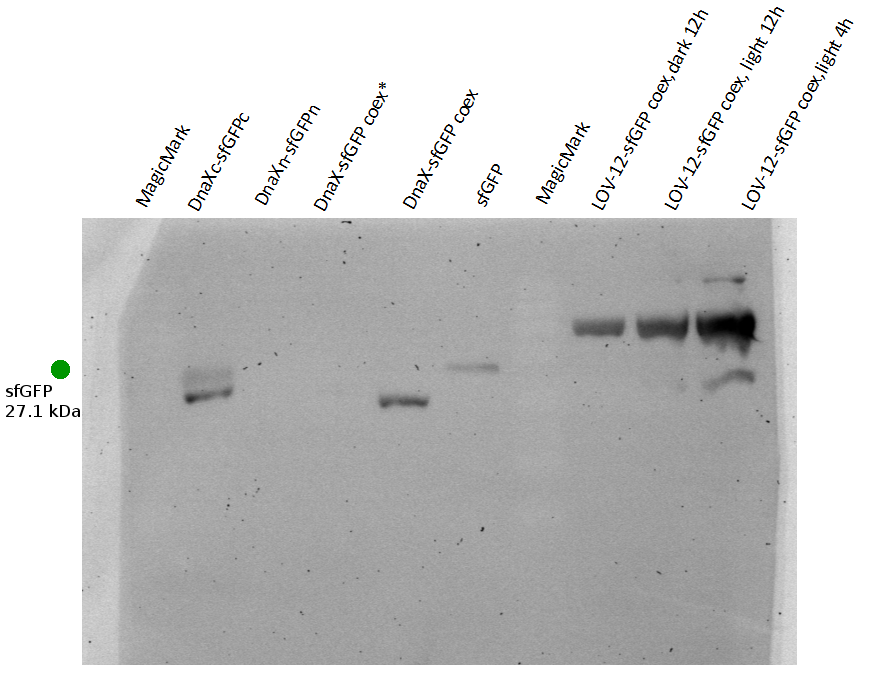

As suspected, the GFP-antibody's epitope seems to lie in the much larger C-terminal half of split sfGFP (Figure 5). It should thus show the bands in the C-terminal single expression and in both splicing and non-splicing coexpression constructs as well as in the LOV-constructs. Surprisingly, we did not recognise any band in the non-splicing C-half which should theoretically be stained by anti-GFP. However, the band in the splicing construct can certainly be identified as C-terminal half next to the sfGFP positive control. We therefore conclude that no intein splicing has taken place for the Ssp DnaX split inteins and split sfGFP.

This conclusion is supported by the data we obtained from flow cytometry.

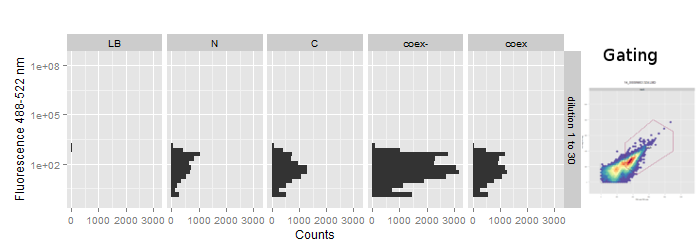

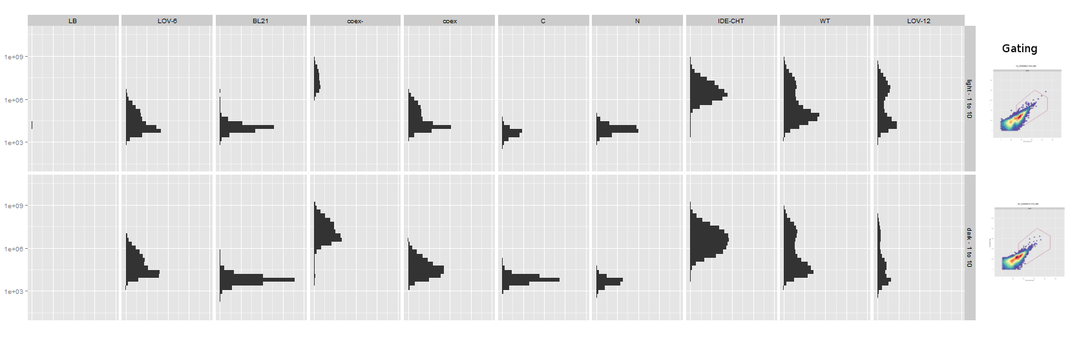

The FACS data was gated on the FSC - SSC scatterplot to separate debris from cells (Figure 6). During acquisition the maximum event count was set to 50000 or 100000 and usually reached within 10 to 30 seconds even at higher dilutions.

The fluorescence at ~488-512nm is plotted on vertical histograms for comparison. Data strongly implies that there is no change in fluorescence in the splicing constructs. This suggests, especially with regard to our previous experience with [2014.igem.org/Team:Heidelberg/Project/Reconstitution Fluorescent Proteins Assembly], that no protein splicing has taken place.

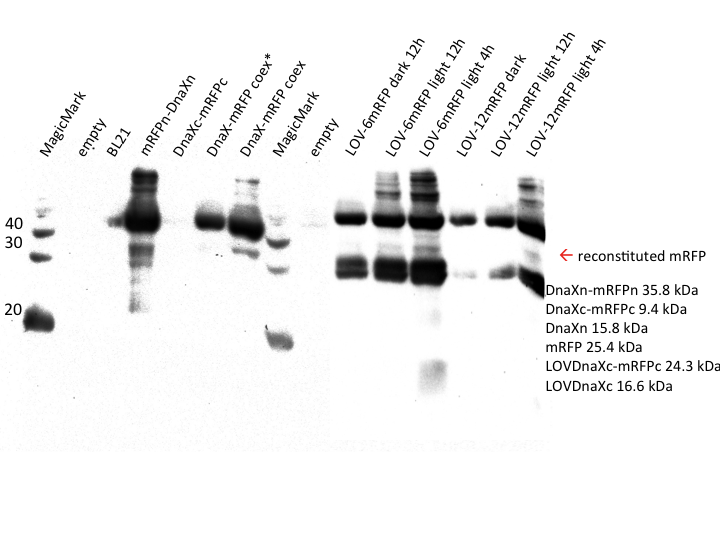

For mRFP, results look much better. Apart from confirming the expression of most constructs, a weak yet clear band is visible in the splicing coexpressed sample at the estimated position of mRFP (25.4 kDa). All proteins in this particular blot seem to have run at higher positions as suggested by the protein ladder. We have previously observed this in our lab and is has proven to be best to carefully compare the protein-bands in one's samples with each other in addition to the ladder. Although the band of reconstituted mRFP is weak it is to be seen alongside the non-splicing control to the left. The blot strongly implies that protein splicing has taken place and mRFP has successfully been reassembled from split halves.

The LOV constructs to the right are somewhat harder to interpret. On the top at around 36 kDa we see the DnaXn-mRFPn fusion protein as we saw it in the coexpression samples. To the bottom, as expected, the LOV-DnaXc-mRFPc construct is found. Inbetween, a weak band is visible at the same size as the reassembled mRFP band in the coexpression sample. We therefore deduce that protein splicing has taken place with the LOV domain constructs. However, the samples that were illuminated for 12 hours show significantly less overall expression than the corresponding sample induced for 4 hours. We hypothesise this is caused by protein degradation or a long-time phototoxic effect that we did not detect in our phototoxicity test. As the non-illuminated control for the 4 hour time point is missing, no clear result for the effect of light induction could be derived yet.

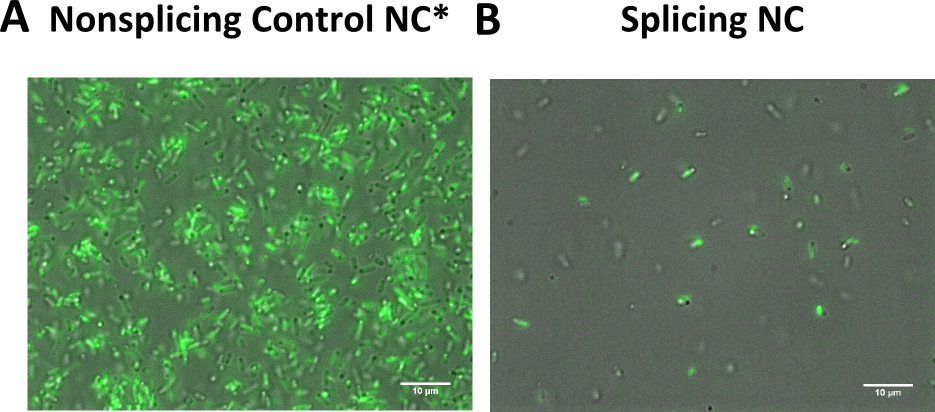

Very interestingly, the FACS analysis of our mRFP cultures revealed a curious behaviour. The mutated (non-splicing) mRFP coexpression samples very obviously show more fluorescence than the splicing samples.

This is supported by fluroescent microscopy pictures, where the supposedly non splicing variants is stronger in fluorescence than the splicing variant (Figure 9).

Discussion

In the context of these experiments, we designed a new approach to regulate intein splicing via light induction. The connection between caging peptides and intein splicing was so far not established in literature. However, this application becomes only possible by the discovery of very small, artificially created C-inteins. We successfully managed to verify the splicing reaction of SspDnaX in the context of split mRFP. However, we were surprised by the low efficiency of the splicing reaction depicted on the Western Blot. Looking deeper in the original papers, we saw that also the authors did not archive higher amount of splicing product using SspDnaX [11]. The usage of split mRFP 168/169 failed as easy read-out of intein splicing, since the the non-splicing samples turned out to be brighter than the splicing construct. It could be due to sterically inhibition caused by the splicing reaction at position 168/169 compared to the flexible assembly by the mere proximity of the split halves. However the reconstitution of mRFP was clearly visible on the Western Blot (Figure 6). Instead, splicing of sfGFP seems to have failed. This can be attributed to the missing extein residues, which we omitted in order to avoid a large amino acid scar in front of the chromophore region. The reconstitution of mRFP is also visible in the samples that include both LOV- mutants and were irradiated by light, but not in the samples that were kept in darkness. However the right control, a LOV-mutant that is kept in the dark for 4 hours is missing. Therefore this experiment needs to be repeated – and we definitely will do so after Wiki freeze! Altogether the regulation of proteins by light is state of the art and a very important tool in molecular biology.

References

[1] Lu, W. et al. Split intein facilitated tag affinity purification for recombinant proteins with controllable tag removal by inducible auto-cleavage. J. Chromatogr. A 1218, 2553–60 (2011).

[2] Wood, D. W., Wu, W., Belfort, G., Derbyshire, V. & Belfort, M. A genetic system yields self-cleaving inteins for bioseparations. 889–892 (2002).

[3] Brenzel, S. & Mootz, H. D. Design of an intein that can be inhibited with a small molecule ligand. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 4176–7 (2005).

[4] iGEM team Queen's University, Kingston, ON, Canada 2014 https://2014.igem.org/Team:Queens_Canada/Project

[5] Deblasio, S. L., Luesse, D. L. & Hangarter, R. P. A Plant-Specific Protein Essential for Blue-Light-Induced Chloroplast Movements 1. 139, 101–114 (2005).

[6] Herrou, Julien, and Sean Crosson. Function, structure and mechanism of bacterial photosensory LOV proteins. Nature reviews microbiology 9.10 (2011). 713-723.

[7] Wu, Yi I., et al. A genetically encoded photoactivatable Rac controls the motility of living cells. Nature 461.7260 (2009), 104-108.

[8] Renicke, Christian, et al. A LOV2 domain-based optogenetic tool to control protein degradation and cellular function. Chemistry & biology 20.4 (2013), 619-626.

[9] Niopek, Dominik, et al. Engineering light-inducible nuclear localization signals for precise spatiotemporal control of protein dynamics in living cells. Nature communications 5 (2014).

[10] Yi, Jason J., et al. Manipulation of Endogenous Kinase Activity in Living Cells using Photoswitchable Inhibitory Peptides. ACS Synthetic Biology (2014).

[11] Lin, Y. et al. Protein trans-splicing of multiple atypical split inteins engineered from natural inteins. PLoS One 8, e59516 (2013).

[12] Jach, G., Pesch, M., Richter, K., Frings, S., & Uhrig, J., F. An improved mRFP1 adds red to bimolecular fluorescence complementation. Nature Methods, 3, 597-600 (2006).

"

"