Team:Waterloo/Deliver

From 2014.igem.org

Deliver

Overview: Delivering Antibiotic Susceptibility in vivo

In order to modify a MRSA population and in turn, have the population able to propagate the modification, a method of delivery is essential. Conjugation, the horizontal transfer of genetic material between bacterial cells, is the proposed method for this delivery.

We decided to use conjugation as our mode of delivery because it has a large carrying capacity. Our silencing systems are quite large and therefore need the appropriate delivery mechanism. While a Staphylococcus virus would be more efficient at transferring DNA to a recipient cell, there are no Staphylococcus viruses that have been found with a carrying capacity large enough to handle our silencing systems.

Conjugation is a transfer of genetic material between prokaryotes by cell-to-cell contact. This process is well characterized in gram-negative bacteria, such as E. coli, but it is less characterized in gram-positive bacteria like Staphylococcus aureus. To infer information on the gram-positive process, microbiologists usually use the gram-negative process as a template (Grohmann et al, 2003).

The conjugation process in both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria all share underlying similarities. For example, an origin of transfer (oriT) is required for all plasmid conjugation. A multiprotein complex that binds to the origin of transfer is called the relaxosome. The proteins involved in the relaxosome are coded within a tra/trs region that can be found on the plasmid or on the chromosome. The relaxosome is recognized by DNA relaxes which are able to perform a single or double stranded cut (depending on the type of system). The DNA released from the cut is then available to transfer to the recipient cells (Grohmann et al, 2003).

Design

Strain Considerations

To test our system in the lab, a Level 1 organism was used as a safety precaution. Staphylococcus epidermidis (ATCC 12228) is a close relative of Staphylococcus aureus and is able to conjugate with S. aureus populations (Forbes and Schaberg, 1983).

Conjugation Machinery

The plasmid pGO1 is of the few gram positive conjugative plasmids studied. The entire 54 kb plasmid has been sequenced by Caryl and O’Neill (2009) (Accession: NC 012547.1). The parts of the pGO1 conjugative plasmid sufficient for trans-species conjugation include a ~ 14 kb trs gene cluster, and a ~2 kb region containing the oriT and a gene which encodes for a nickase protein (Climo et al., 1996).

Experiment

In order to test the conjugation machinery in S. epidermidis, we sought to construct a conjugative plasmid containing the oriT region and trs region from pGO1. The plasmid should maintain a low copy number to ensure a lower metabolic load imposition which would increase the chance of acceptance by the cell. The low copy, theta replicating oriV from the Staphylococcal plasmid pSK41 (BBa_K1323018) was a great candidate. An erythromycin resistance gene (BBa_K1323011) was chosen as the selection marker and DsRed (BBa_K1323015) (Figure 1) was chosen as a reporter to track the movement of the plasmid.

DsRed fluorescence was analyzed in both E. coli and S. epidermidis. The DsRed cassette (BBa_K1323015) was incorporated into a pUC57 plasmid containing an erythromycin resistance gene (BBa_K1323011) and Staphylococcal oriV (BBa_K1323018). This plasmid was transformed into the strains using heat shock for E. coli and electroporation for S. epidermidis. Pellets from 50 ml overnight cultures were collected into 1.5 ml eppendorf tubes. To the naked eye (A) E. coli has a pink color (left), whereas in S. epidermidis (middle), a slight pink colour could only be noticed if compared to S. epidermidis without the construct (right). When seen under a RFP filter (B) a high degree of red fluorescence was observed in E. coli (left) and a lower degree of red fluorescence was seenin S. epidermidis (middle). The S. epidermidis negative control (right) showed no observable fluorescence.

Since construction of this plasmid would take place in E. coli, the parts would be cloned into the pSB1A3 backbone. The final conjugational plasmid to test in the lab is shown in Figure 2.

The design for the final test plasmid for conjugation. The plasmid contains the trs and nes regions from pGO1 which are essential for conjugation, a DsRed reporter gene (fluoresces red), and erythromycin resistance gene as a selective marker in Staphylococci, a low copy Staphylococci origin of replication, within the pSB1A3 backbone which contains a high copy E. coli origin of replication and ampicillin selection marker.

The pGO1 plasmid was graciously sent to us by Dr. Alex O’Neill’s lab at the University of Leeds. The region containing the oriT and nickase protein (position 8021-10264 on the pGO1 plasmid) was successfully PCR amplified, cloned into pSB1C3, and sent to the registry as a biobrick (BBa_K1323003). Amplification and cloning of the trs region (position 23723 - 37201 on the pGO1 plasmid) is still in progress. Once this conjugational plasmid is constructed, mating assays will be performed between S. epidermidis to ensure all parts are functional.

Design Considerations

The antibiotic resistance genes on the plasmid were used as a means to work with the constructs in the lab. However, they would be problematic if this design was implemented as a treatment for MRSA so we propose that these genes be removed in the final product

Modelling

We model the propagation of our plasmid for a number of reasons. Most importantly, we want to determine the optimal time to apply antibiotics to the infection. To do so, we track the total number of donor, recipient, and transconjugant cells and define the “fall time” as the time it takes the number of recipients to reach 10% its initial value. In addition to determining when to apply methicillin, the model can be used to find how large of a conjugation rate is needed and what initial concentration of donor cells is needed to spread the plasmid at a fast enough rate. Unfortunately, modeling such a system poses quite a bit of difficulty. The primary obstacle is that we consider S. aureus growth on a solid surface (e.g. a lab plate, or on your skin) and not in a well mixed environment. This forces us to abandon more traditional models of conjugation (such as from Levin, Stewart, and Rice) and develop a spatial model instead. We took two main approaches to developing such a model: an agent-based model (ABM), and a partial differential equation (PDE) model. To see more on the PDE please see the Math Book

Conjugation Efficiency

The typical conjugation frequency of a Staphylococcus conjugative plasmid is around 5.8 x 10-7 (Projan and Archer, 1989).The rate of transfer will ultimately need to be improved if enough cells of MRSA are to be infected by our construct.

Agent-Based Model Overview

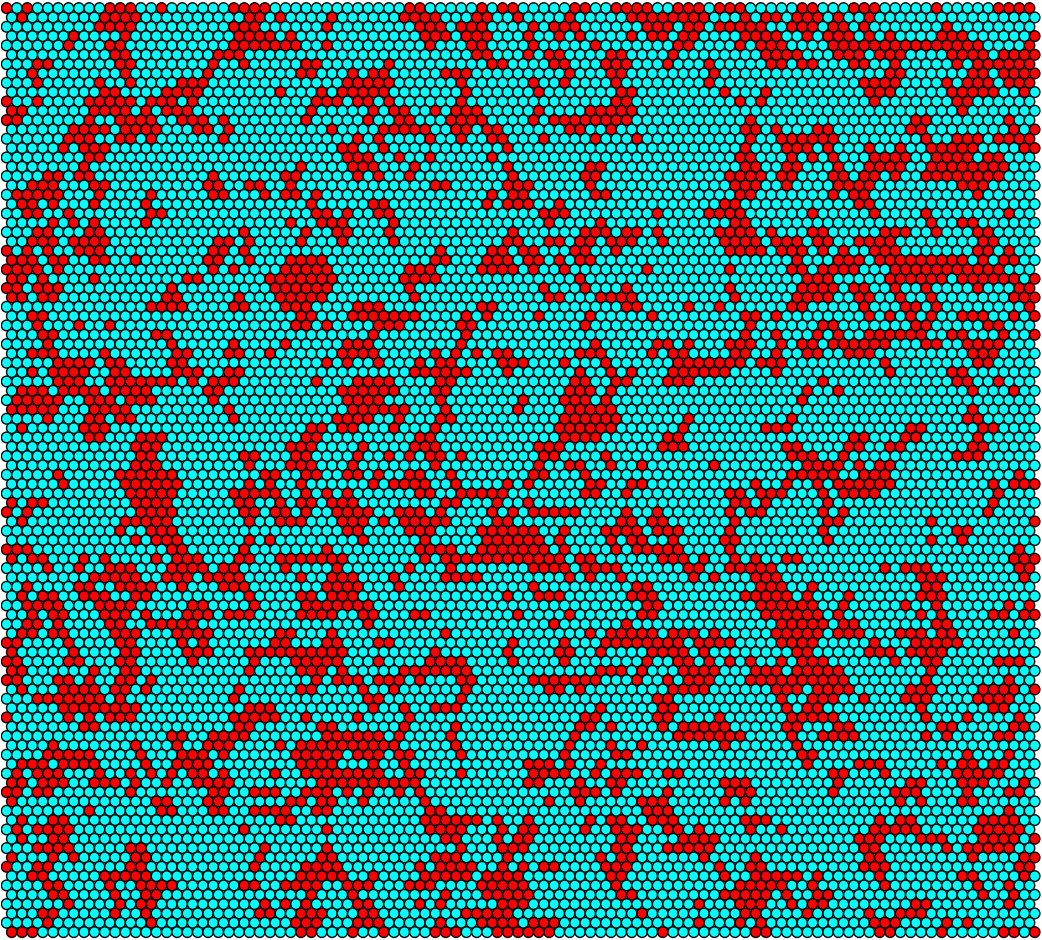

We have developed a novel model for Staphylococcal conjugation on flat surfaces.The ABM is a stochastic simulation of conjugation through a population of donor and recipient cells. The main advantages of this model are that it accounts for randomness of plasmid transfer, as well as likely maintaining accuracy on small-scale areas. By treating each bacterium as an “agent” that has properties associated with its type (either Donor or Recipient), and letting the group of agents interact over a prescribed period of time, one can make qualitative and quantitative conclusions about their behaviour. The model is based on the idea of having hexagonal cells that each may or may not be occupied by a donor (e.g. modified S. epidermidis) or a recipient (e.g. MRSA). An individual bacterium may divide into an empty neighbouring cell. If the cell is a donor, it has a chance to conjugate with an adjacent recipient. We assume that the conjugative plasmid represses methicillin-resistance 100% (i.e. all donor cells will die upon introduction of antibiotic). The following figures are graphical output from the agent-based model. The figures on the left correspond to the idealized model parameters, while those on the right correspond to S. aureus parameters found in literature. The most significant parameter distinction is the conjugation period, which is 10 hours/conjugation in the “ideal” model parameter, but roughly 10^7 hours/conjugation for S. aureus.

Figure 3: Conjugation simulation output at t=0h (Left: idealized rates, Right: S. aureus rates)

Figure 4: Conjugation simulation output at t=6h (Left: idealized rates, Right: S. aureus rates)

Figure 5: Conjugation simulation output at t=12h (Left: idealized rates, Right: S. aureus rates)

Figure 6: Conjugation simulation output at t=24h (Left: idealized rates, Right: S. aureus rates)

Based on the simulations, it can be concluded the wild-type conjugative frequency for S. aureus is too low for this to be a valid delivery system of our silencing systems. To this effect, we plan to subject the trs region to error prone PCR to produce many different variants of it. The mutant colonies will then be filter mated and screened for improved conjugation efficiency.

References

Caryl, J. A, and O’Neill, A. J. (2009). Complete nucleotide sequence of pGO1, the prototype conjugative plasmid from the Staphylococci. Plasmid, 62(1), 35–8

Climo, M. W., Sharma, V. K., and Archer, G. L. (1996). Identification and Characterization of the Origin of Conjugative Transfer (oriT) and a Gene (nes) Encoding a Single-Stranded Endonuclease on the Staphylococcal Plasmid pGO1. Journal of Bacteriology, 178 (16): 4975-83

Forbes, B. A., and Schaberg, D. R. (1983). Transfer of resistance plasmids from Staphylococcus epidermidis to Staphylococcus aureus: evidence for conjugative exchange of resistance. Journal of Bacteriology, 153(2), 627–634.

Grohmann, E., Muth, G., Espinosa, M., Grohmann, E., & Espinosa, M. (2003). Conjugative Plasmid Transfer in Gram-Positive Bacteria. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews, 67(2), 277–301.

Malizewski, K. and Nuxoll, A. (2014) Use of electroporation and conjugative mobilization for genetic manipulation of Staphylococcus epidermidis. Chapter 11. Staphylococcus Epidermidis. Editor, P. D. F., & Walker, J. M. 125-127.

"

"