Team:Cornell/project/wetlab/mercury

From 2014.igem.org

Wet Lab

Construct Design

To allow for the transport and sequestration of mercury ions into E. coli cells, genes that encode for the cellular production of heavy metal transport proteins and metallothioneins have been added to the pSB1C3 high copy bacterial plasmid. The mercury transport system is composed of merT and merP, genes originally found in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. merP is a periplasmic mercury ion scavenging protein. merT is an integrated membrane protein that works to transport mercury ions into the cell’s cytoplasm.[1] The merT and merP coupled transport system has been used in previous studies to develop luminescence based biosensors for the detection of mercury in the surroundings of bacterial cells.[2]Our BioBrick BBa_K1460004 is composed of the Anderson promoter followed by a ribosomal binding site, merT, merP, and a terminator. The constitutive Anderson promoter allows for the constant expression of metal uptake proteins within our engineered E. coli. The BioBrick BBa_K1460007 is a composite of parts BBa_K1460004 and BBa_K1460001, and it contains the mercury transport proteins (along with promoter, ribosomal binding site, and terminator) upstream of the GST-crs5 metallothionein gene in pSB1C3. By coupling the merT and merP system with metallothionein, we hope to develop an effective biological system for our cells to uptake mercury ions and bind intracellularly to metallothioneins.

BBa_K1460007

Results

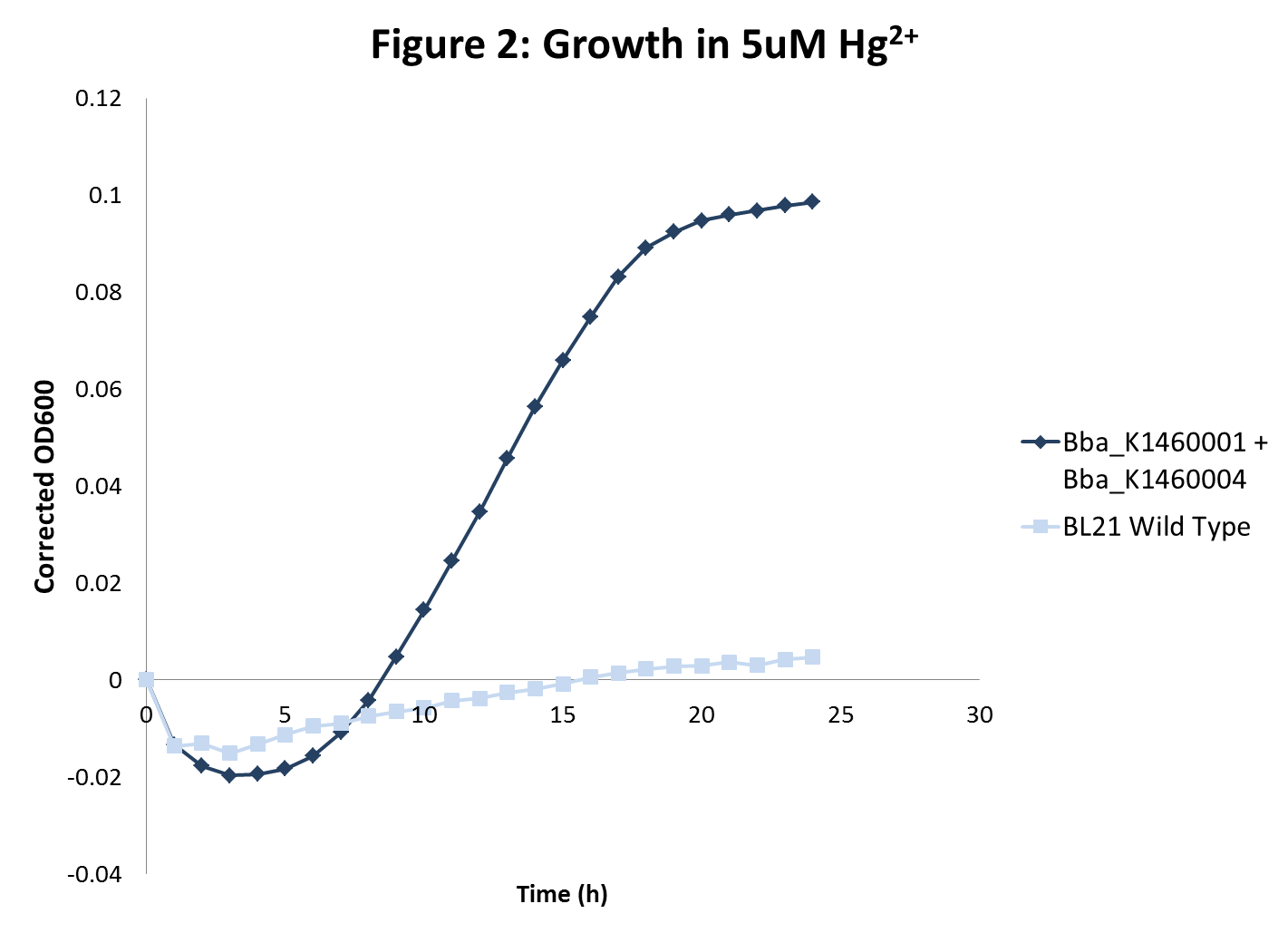

Cells successfully expressing merT and merP should be transporting more mercury ions past the cell wall. This would lead to increased mercury sensitivity. Additionally, cells expressing merT and merP as well as metallothionein should have increased tolerance to mercury due to the presence of metallothionein. To test for mercury sensitivity, E.coli BL21 and engineered BL21 with part BBa_K1460004 in the cmr plasmid pSB1C3 were grown for a 24 hour period in LB with .5 uM Hg (a mercury concentration we found to have moderate toxicity to wild type BL21 cells). To test for increased metal tolerance, we grew E.coli BL21 and engineered BL21 with parts BBa_K1460001 (GST-crs5 in pSB1C3) and BBa_K1460004 (merT/merP in pUC57) in 5 uM Hg (a mercury concentration we found to be very toxic to wild type BL21 cells).

What we observe in both cases is what we expect. We see that BL21 engineered with BBa_K1460004 has impaired growth when compared to wild type BL21 (figure 1). This suggests that, in fact, BBa_K1460004 acts as expected and engineered cells successfully transport more mercury ions past the membrane than wild type cells. When BL21 engineered with both merT/merP and GST-crs5 are grown in a highly toxic concentration of mercury we see significant growth when in wild type BL21 we do not (figure 2). This suggests that these cells are successfully expressing metallothionein and that this metallothionein is providing the cells with an inherent resistance to mercury toxicity.

Part BBa_K1460004 in pUC57 was co-transformed with part BBa_K1460001 (GST-crs5) in pSB1C3 and selected for with both ampicillin and chloramphenicol to effectively create the mercury sequestration part BBa_K1460007. To test for sequestration efficiency, both BL21 and BL21 engineered with BBa_K1460001 and BBa_K1460004 were grown with LB + 0.1% Arabinose for 8 hours and then diluted in half with LB + 2 mM Hg for a final mercury concentration of 1 mM. These cultures were grown for 8 more hours. The cells were then removed and supernatant was tested for mercury concentration using Inductively Coupled Plasma Atomic Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-AES) with the help of Cornell's Nutrient Analysis Lab. Error bars in chart represent standard deviation of three biological replicates.

Part BBa_K1460004 in pUC57 was co-transformed with part BBa_K1460001 (GST-crs5) in pSB1C3 and selected for with both ampicillin and chloramphenicol to effectively create the mercury sequestration part BBa_K1460007. To test for sequestration efficiency, both BL21 and BL21 engineered with BBa_K1460001 and BBa_K1460004 were grown with LB + 0.1% Arabinose for 8 hours and then diluted in half with LB + 2 mM Hg for a final mercury concentration of 1 mM. These cultures were grown for 8 more hours. The cells were then removed and supernatant was tested for mercury concentration using Inductively Coupled Plasma Atomic Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-AES) with the help of Cornell's Nutrient Analysis Lab. Error bars in chart represent standard deviation of three biological replicates.

There was no statistically significant difference between BL21 wild type and BL21 engineered to express merT/merP and GST-crs5 in final culture concentration of mercury or mercury sequestered per OD. This result prevents us from definitively confirming that the engineered bacteria are capable of sequestering mercury. The mercury concentrations used in this test were much higher than was shown in growth experiments to completely prevent growth of BL21, so it is likely that cells were quickly killed once metal was added, possibly confounding results. To verify this construct is successful in removing mercury from water, we must repeat these experiments using lower concentrations of Hg. We were not able to complete these experiments, however, as the limit of detection of the ICP-AES used to test these metal concentrations is above the uM range necessary to conduct these experiments.

References

- Lund, P., & Brown, N. (1987). Role of the merT and merP gene products of transposon Tn501 in the induction and expression of resistance to mercuric ions. Gene, 207-214.

- Omura, T., Kiyono, M., & Pan-Hou, H. (2004). Development of a Specific and Sensitive Bacteria Sensor for Detection of Mercury at Picomolar Levels in Environment. Journal of Health Science, 379-383.

"

"