Team:Bielefeld-CeBiTec/Project/CO2-fixation/Carboxysome

From 2014.igem.org

Module II - Carbon Dioxide (CO2) Fixation

Carboxysome

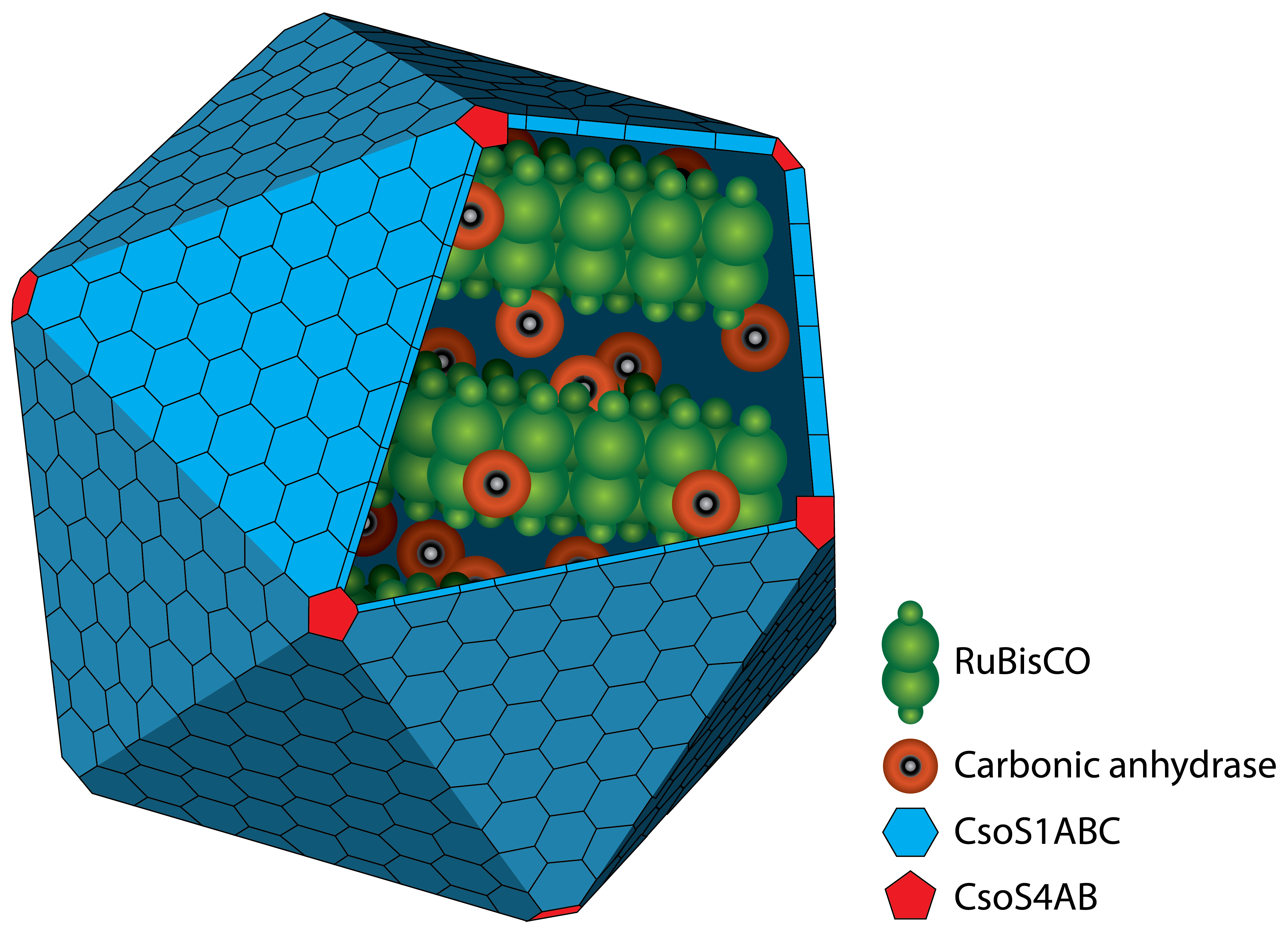

Figure 1: Schematic view of the carboxysome. The RuBisCO and the carbonic anhydrase are surrounded by different carboxysomal shell proteins, which form a defined structure. The carbon fixation takes places inside the carboxysome.

A carboxysome is a bacterial microcompartiment (BMC) surrounded by a protein shell. Naturally they occur in CO2 fixing bacteria like cyanobacteria. Therefore they are the enzyme-containing organelles for these metabolic pathways (Bonacci et al., 2011; Shively et al., 1973). The first carboxysomes were discovered in 1956 (Drews, Niklowitz 1956), and the first characteization was described by Shively et al., 1973.

Carboxysomes are formed by different shell proteins, surrounding an enzyme-containing lumen, which is rigorously separated from the cytoplasm. Thus, the possibility is given to enable reaction pathways strictly with the conditions in the cytoplasm. A schematic image of the carboxysome is given in figure 1.

The protein shell consists of two different types of proteins. Pentamers are used for the vertices of the icosaeder and hexamers for the facets. The main constituent of the shell is the CsoS1A protein, which contributes around 13 % of the total protein mass. Carboxysomes are between 80 and 120 nm in diameter (Kehrfeld et al., 2005) (figure 1). In the interior, there are two different types of enzymes. On the one hand there is

RuBisCO which catalyzes the carboxylation or oxygenation of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate. This reaction is one essential step in the Calvin cycle, the pathway for carbon fixation in autotrophic bacteria. On the other hand there is the carbonic anhydrase which converts hydrogen carbonate (HCO3-) to carbon dioxide. The resulting carbon dioxide is the substrate for RuBisCO.

Generally, there are two different types of CBs found, called α-type (cso-carboxysome) and β-type (ccm-carboxysome) carboxysomes. This classification is based on differences in their component proteins and organization of their corresponding genes (Batger et al., 2002 (b)).

α-type carboxysomes are found in α-cyanobacteria like some Synechococcus species or the chemoautotroph organism Halothiobacillus neapolitanus. This type of carboxysome contains the type I RuBisCO. Furthermore the respective genes for the carboxysome are arranged in a single operon. In β-type carboxysomes type II RuBisCO, containing no small subunits, occurs. In contrast to α-type carboxysomes, the genes are arranged in multiple gene clusters. (Batger et al., 2002 (b); Bonacci et al., 2011; Yeates et al., 2008) A possible difference in functionality between both types of carboxysomes is not yet fully understood (Yeates et al., 2008).

The advantage of the microcompartiment is the concentration of carbon dioxide in its lumen. Carboxysomes play a central role in carbon concentrating mechanisms (CCM) (Bonacci et al., 2011; Yeates et al., 2008) The reactions inside the carboxysome are illustrated in figure 2. This mechanism is used for the accumulation of CO2 in autotrophic prokaryotes. The carboxysome as a place of carbon dioxide fixation was first described by Reinhold et al., 1990. The first reaction of the CCM is the transport of atmospheric carbon dioxide or hydrogencarbonate (HCO3-) into the cells. Accumulation of inorganic carbon is achieved by transmembrane pumps and transporters localized in the cell membrane. At physiological pH values of around 7, the equilibrium is clearly on the side of hydrogencarbonate. Hydrogencarbonate is able to diffuse across the shell of the carboxysome. The carbonic anhydrase (CA), located inside the carboxysome, catalyzes the conversion of hydrogencarbonate to gaseous carbon dioxide surving as substrate for RuBisCO. The CA is associated with the shell and presents only a small number of the carboxysome proteins. CA, also called CSOS3, acts to saturate the lumen with carbon dioxide and enables high effective concentrations of CO2, due to this RuBisCO is able to work near its maximal reaction rate with high specificity. The product of RuBisCO, 3-phosphoglycerate, is used in the metabolism of the cells. (Batger et al., 2002 (a); Bonacci et al., 2011; Yeates et al., 2008) Diffusive loss of carbon dioxide is probably provided by the outer shell as it acts as a barrier.

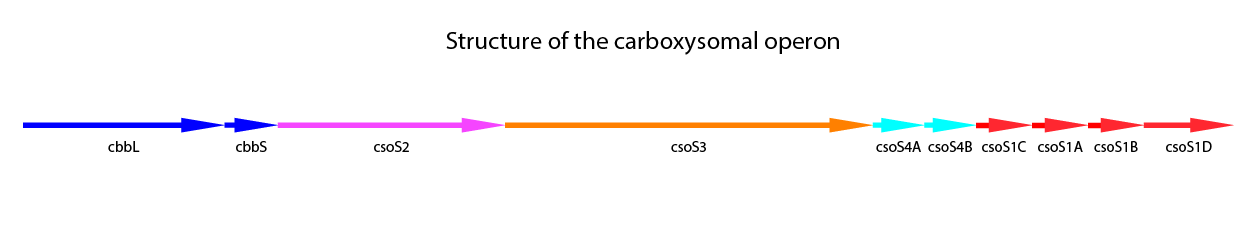

Halothiobacillus neapolitanus is a model organism for carboxysomes. This organism is a Gram-negative proteobacterium which belongs to the purple sulfur bacteria. It is obligate aerob and chemolitoautotroph. H. neapolitanus expresses the α-type carboxysome (cso-carboxysome). This type of carboxysome is the most abundant carboxysome in oligotrophic oceans. It has to be distinguished from the ccm-carboxysome (β-type). Recent studies have been made on this organism concerning the carboxysome (Bonacci et al., 2011; Cannon, Shively 1983; Holthuijzen et al., 1986; So et al., 2004). The carboxysomal operon includes nine genes. One more gene, csoS1D located outside of the core operon was found. (Bonacci et al., 2011) A structural overview of of the core operon and csoS1D is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Schematic mapping of the caboxysomal gene of Halothiobacillus neapolitanus. csoS1D is also shown here, although it is not found in the carboxysomal operon.

The additional genes in the carboxysomal operon are related to the shell proteins. CsoS1A-C are the main shell proteins, building up the structure of the carboxysome. CsoS1A is responsible for the hexameric quaternary structure and is the major component of the CB shell. The gene csoS1D is not localized in the carboxysomal operon. It is assumed, that CsoS1D may modify function of CBs and influences the shell permeability. Furthermore it has been shown, that CsoS1D reduces the number of CBs with shell defects. (Bonacci et al., 2011) Another shell protein is CsoS2, which has a size of 80-90 kDa. The exact function of CsoS2 is still unknown (Batger et al., 2002 (a); Yeates et al., 2008). CsoS2 is characteristic for α-type carboxysomes. It seems to have no enzymatic activity and is localized primarily in the periphery of the carboxysome (Yeates et al., 2008). CsoS4A and CsoS4B are responsible for the vertices of the icosahedral shell, which can be deduced from the crystal structures. In the carboxysome both proteins are present equimolar, but in very low amounts. Knockout of both genes gives rise to more leaky carboxysomes, indicating a loss in the permeability barrier function of the shell. (Cai et al., 2009) In Table 1 a summary of the carboxysomal proteins including CsoS1D is shown.

Carboxysomes enable efficient fixation of CO2 in bacteria. For this reason, we want to use the α-type carboxysome from the model organism Halothiobacillus neapolitanus in our project and express it recombinantly in E. coli. We intend to use the carboxysomal operon including csoS1D shown in figure 3.

| Protein | Function |

|---|---|

| CsoS1A | Main shell protein, building up the structure of the carboxysome. It is responsible for the hexameric quaternary structure of the carboxysome. |

| CsoS1B | Main shell protein, building up the structure of the carboxysome. |

| CsoS1C | Main shell protein, building up the structure of the carboxysome. |

| CsoS1D | Shell protein. Exact function unknown. Assumed to modify the function of CBs and influence the shell permeability. |

| CsoS2 | Unknown |

| CsoS3 | Carbonic anhydrase (CA). The CA catalyzes the conversion of hydrogencarbonate to gaseous carbon dioxide. |

| CsoS4A | CsoS4A is responsible for the vertices of the icosahedral shell structure. Involvment in the shell permeability is suspected. |

| CsoS4B | CsoS4B is responsible for the vertices of the icosahedral shell structure. Involvment in the shell permeability is suspected. |

References

-

Batger, Price 2002 (a). CO2 concentrating mechanisms in cyanobacteria: molecular components, their diversity and evolution Journal of Experimental Botany, vol. 54, pp. 609-622

-

Batger et al., 2002 (b). Evolution and diversity of CO2 concentrating mechanisms in cyanobacteria Functional Plant Biology, vol. 29, pp. 161-173

-

Bonacci, Walter, Poh K. Teng, Bruno Afonso, Henrike Niederholtmeyer, Patricia Grob, Pamela A. Silver, und David F. Savage. „Modularity of a Carbon-Fixing Protein Organelle“. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109, Nr. 2 (1. Oktober 2012): 478–83. doi:10.1073/pnas.1108557109.

-

Cai et al., 2009. The Pentameric Vertex Proteins Are Necessary for the Icosahedral Carboxysome Shell to Function as a CO2 Leakage Barrier PLoS ONE, vol.4, pp. 1-9

-

Cannon, Shively 1983. Characterisation of a Homogenous Preparation of Carboxysomes from Thiobacillus neapolitanus. Archive of Microbiology, vol. 134, pp. 52-59

-

Drews, Niklowitz 1956. Cytology of cyanophycea.II. Centroplasm and granular inclusions of Phormidium uncinatum, Archive of Microbiology, vol. 24, pp. 147-162

-

Holthuijzen et al., 1986. Protein composition of the carboxysomes of Thiobacillus neapolitanus. Archive of Microbiology, vol. 144, pp. 398-404

-

Kerfeld et al., 2005. Protein structures Forming the Shell of Primitative Bacterial Organelles. Science, vol. 309, pp. 936-938

-

Reinhold et al., 1990. A model for inorganic carbon fluxes and photosynthesis in cyanobacterial carboxysomes. Canadian Journal of Botany, vol. 69, pp. 984-988

-

Shively et al., 1973. Electron Microscopy of the Carboxysomes (Polyhedral Bodies) of Thiobacillus neapolitanus. Canadian Journal of Botany, vol. 69, pp. 984-988

-

So et al., 2004. A Novel Evolutionary Lineage of Carbonic Anhydrase (ε Class) Is a Component of the Carboxysome Shell. Journal of Bacteriology, vol. 166, pp. 1405-1411

-

Yeates et al., 2011. Protein-based organelles in bacteria: carboxysomes and related microcompartments. Nature Reviews Microbiology, vol. 6, pp. 681-691

"

"