|

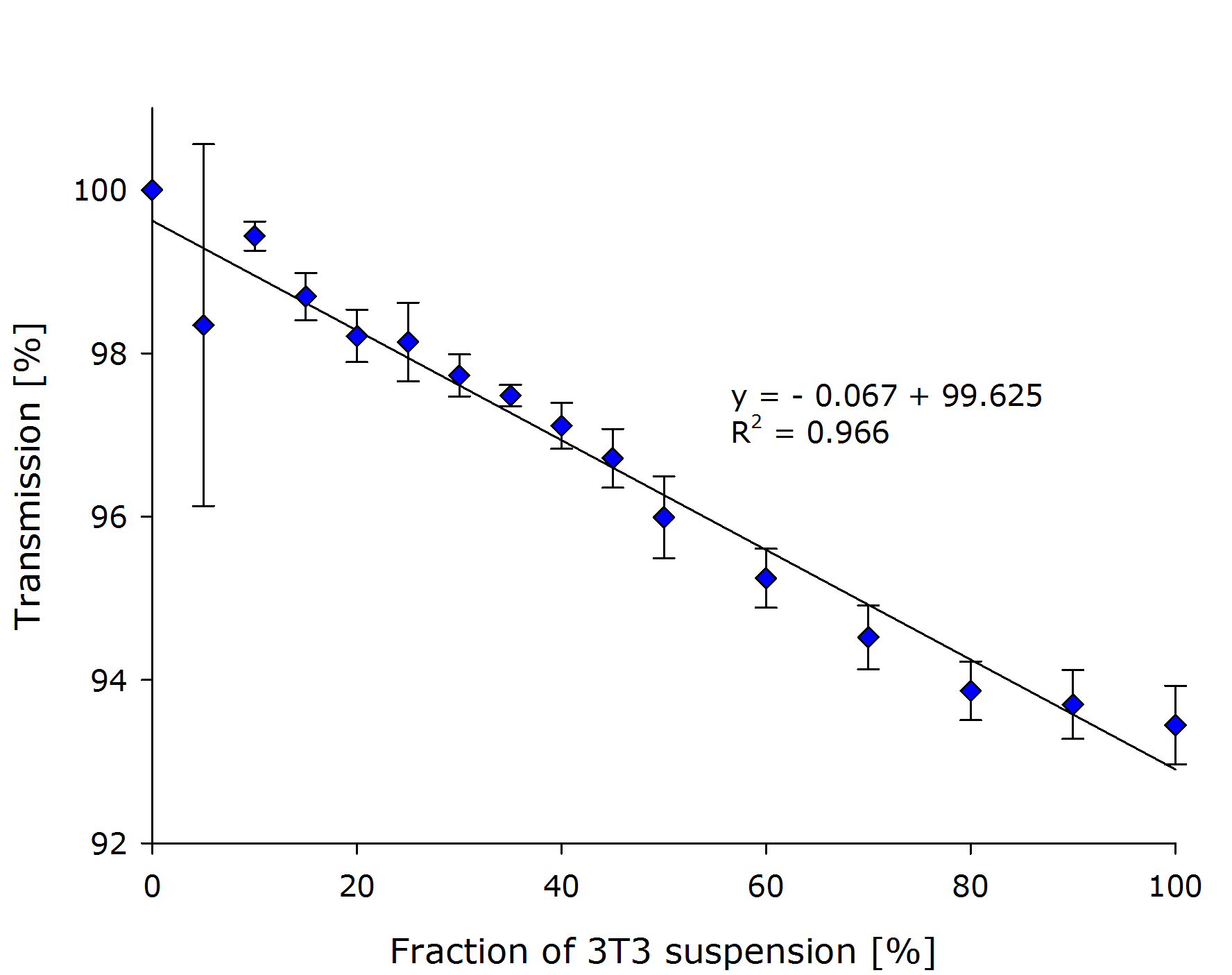

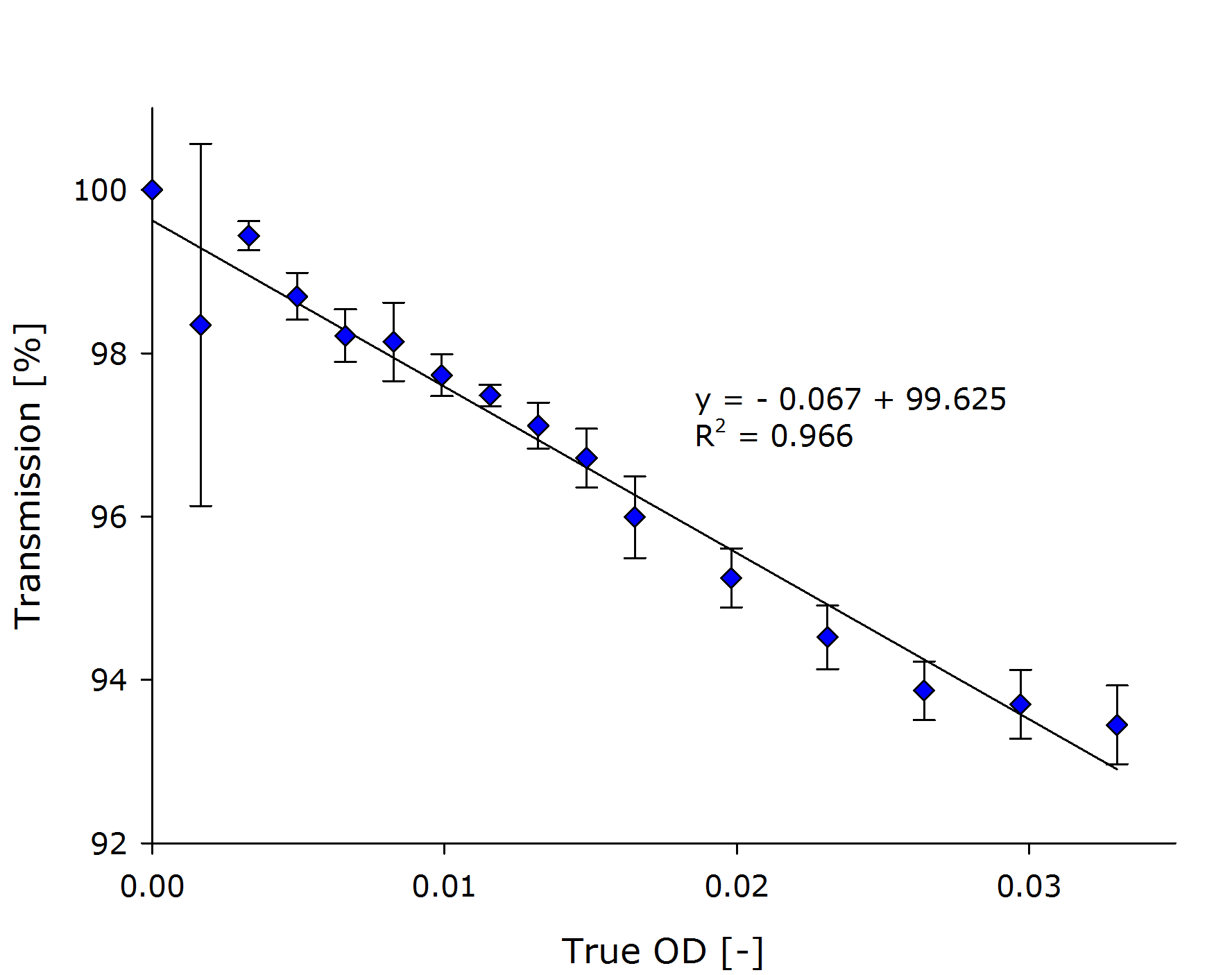

At the iGEM meetup in Munich in May, members of both of our teams realized that our projects share a common objective: Analyzing 2-dimensional, visual signals. For the following months, we stayed in contact and developed a concept to encode information in 384-well plates in the form of data matrix codes.

At the beginning of September, Michael spontaneously took a train to Freiburg and we met face-to-face for several hours to exchange details on our cooperation and general iGEM experiences.

Data Matrix Masks

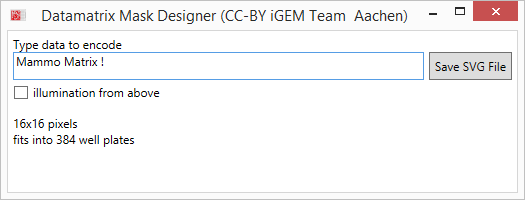

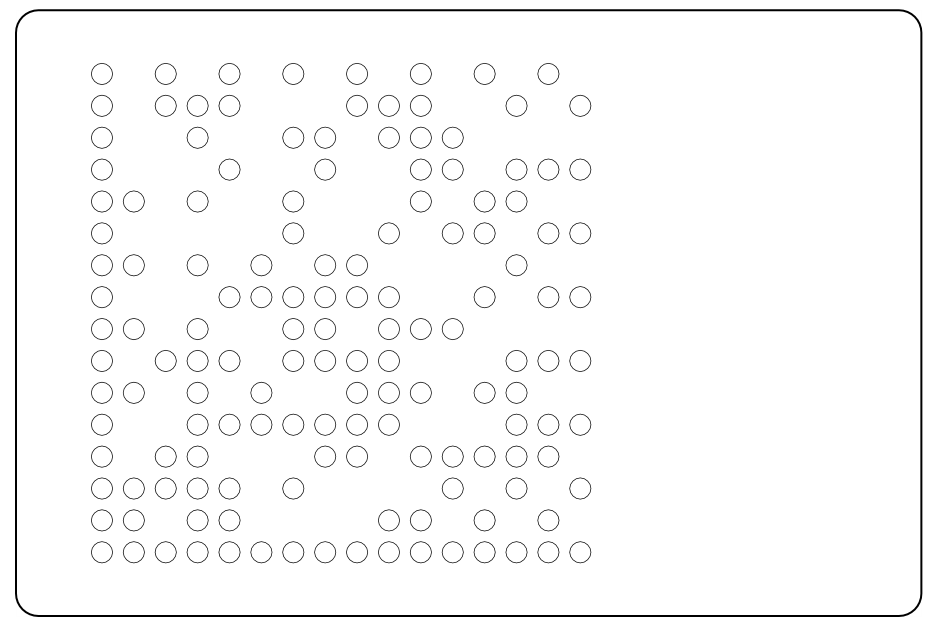

We decided to use masks to locally induce the cells in 384-well plates in a data matrix pattern. To enable us to quickly design masks for different data to be encoded, we wrote a software to easily generate SVG-files for a laser cutter.

After a string has been entered in the designer, an SVG-file can be saved and used for laser cutting the mask:

Get the DatamatrixMaskDesigner to make you own AcCELLoMatrixes! (requires Windows 7/8)

You can also download the full source code and compile or modify it with Visual Studio (Express) 2013.

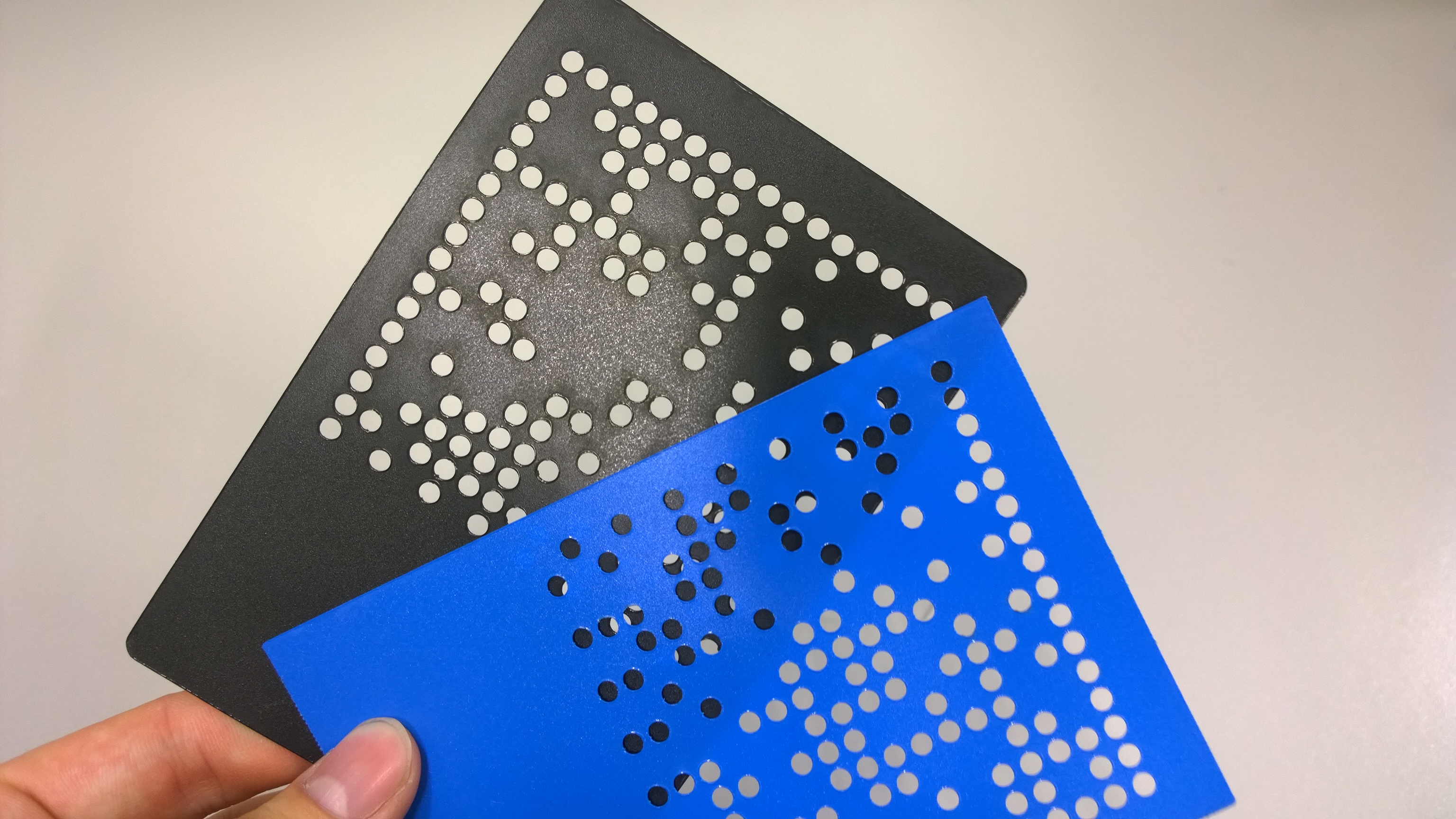

For the first experiments, we cut two different data matrix patterns from polypropylen foil. The masks can be used to cover the plates from the top or from the bottom.

AcCELLoMatrix Reader App

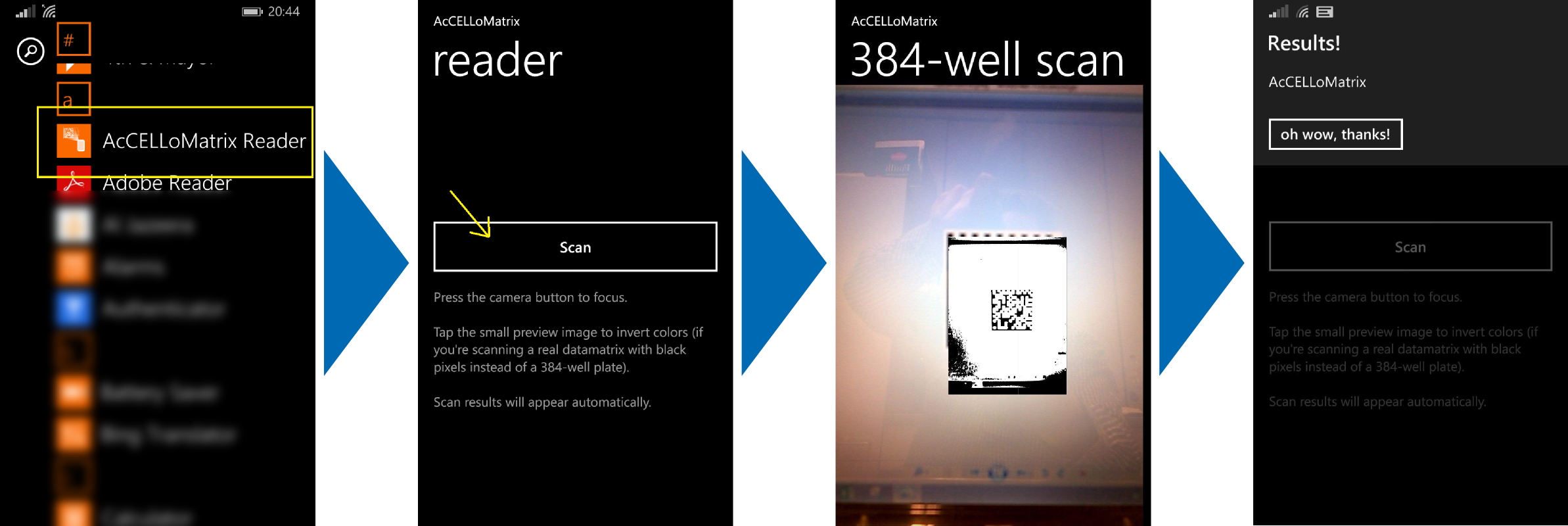

After mask have been designed and the information was encoded into the well plate by selectively illuminating the cells, how do you get it out again? We made an app for that: the AcCELLoMatrix Reader for Windows Phone 8.

We designed the app to be easy to use: A user can simply open the app

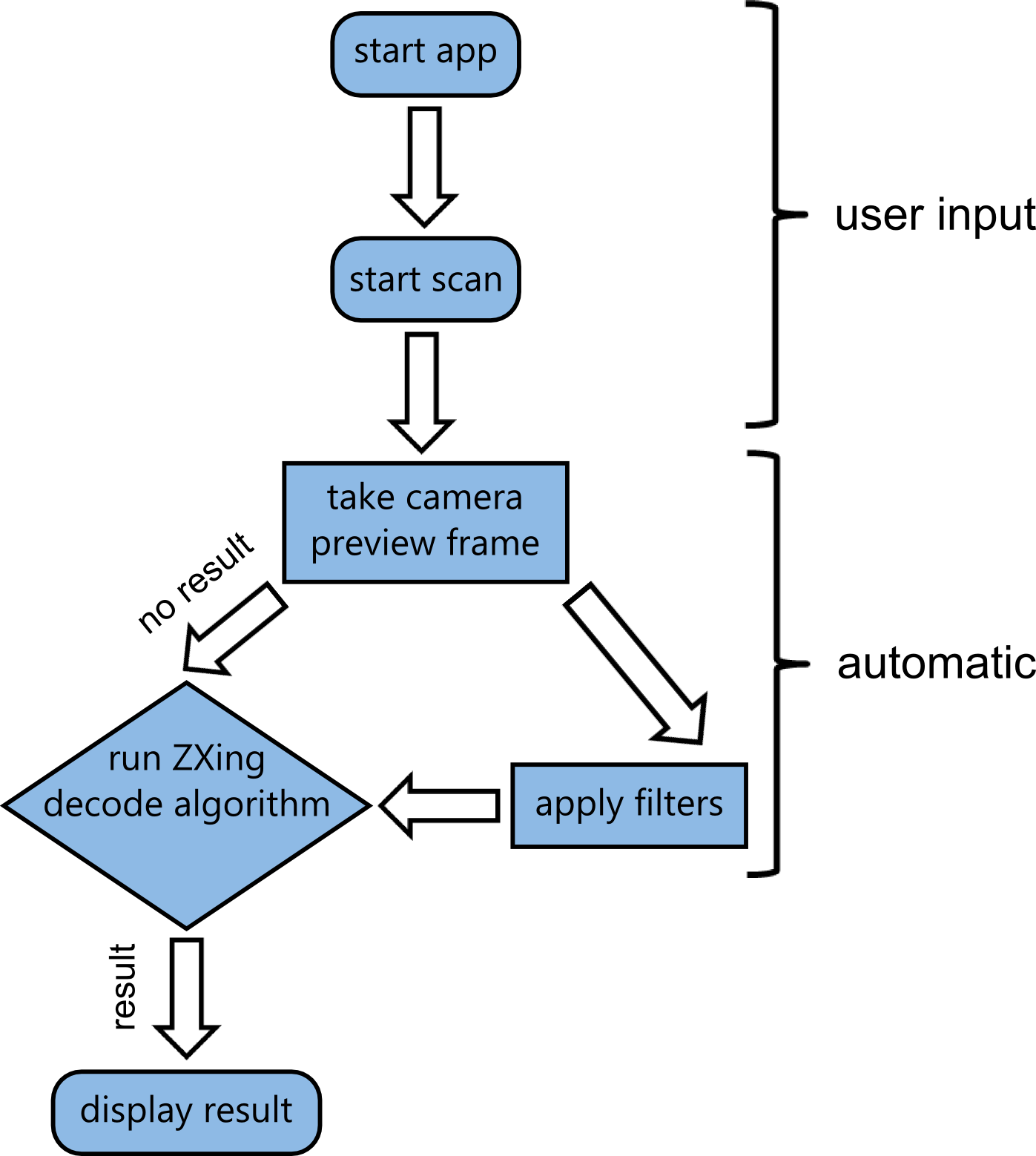

While the apps frontend is designed to be very minimalistic, there's actually going on a lot in the backend. Visual data coming from the camera feed has to be processed and fed into the ZXing decoding algorithm.

Outlook

Due to the circumstance that this collaboration was started relatively late, we have not been able to test the decoding of real AcCELLoMatrixes. But we are confident, that with some threshold adjustments to the AcCELLoMatrixes Reader app and maybe the hole-size of the polypropylen masks, the coding and decoding of short text information in the genetic state of mammalian cells in a 384-well plate is perfectly possible.

References

- [http://www.nuget.org/packages/ZXing.Net/ ZXing.NET] by Michael Jahn is a port of ZXing ("zebra crossing"), both licensed under [http://www.apache.org/licenses/LICENSE-2.0 Apache 2.0]

|

"

"