Evaluation of the Optical Density Measurement

From Transmittance to True Optical Density

At very low levels, uncorrected photometric determinations of cell densities show a decreasing proportionaility to actual cell density.

This can also be observed using our device.

In general, photometric determination of bacterial concentrations depends primarily on light scattering, rather than light absorption. Therefore, often not absorption is measured, but transmittance. For this, the relationship between optical density (OD) and transmitted light $\frac{I_0}{I}$ exists as:

$$ OD = \frac{I_0}{I} = \kappa \cdot c$$

where $I_0$ is the intensity of incoming light and $I$ the amount of the light passing through.

However, this equation is linear only in a certain range.

While one can tackle this non-linearity by using dilutions of the culture, correcting the error systematically is another way to overcome this limitation.

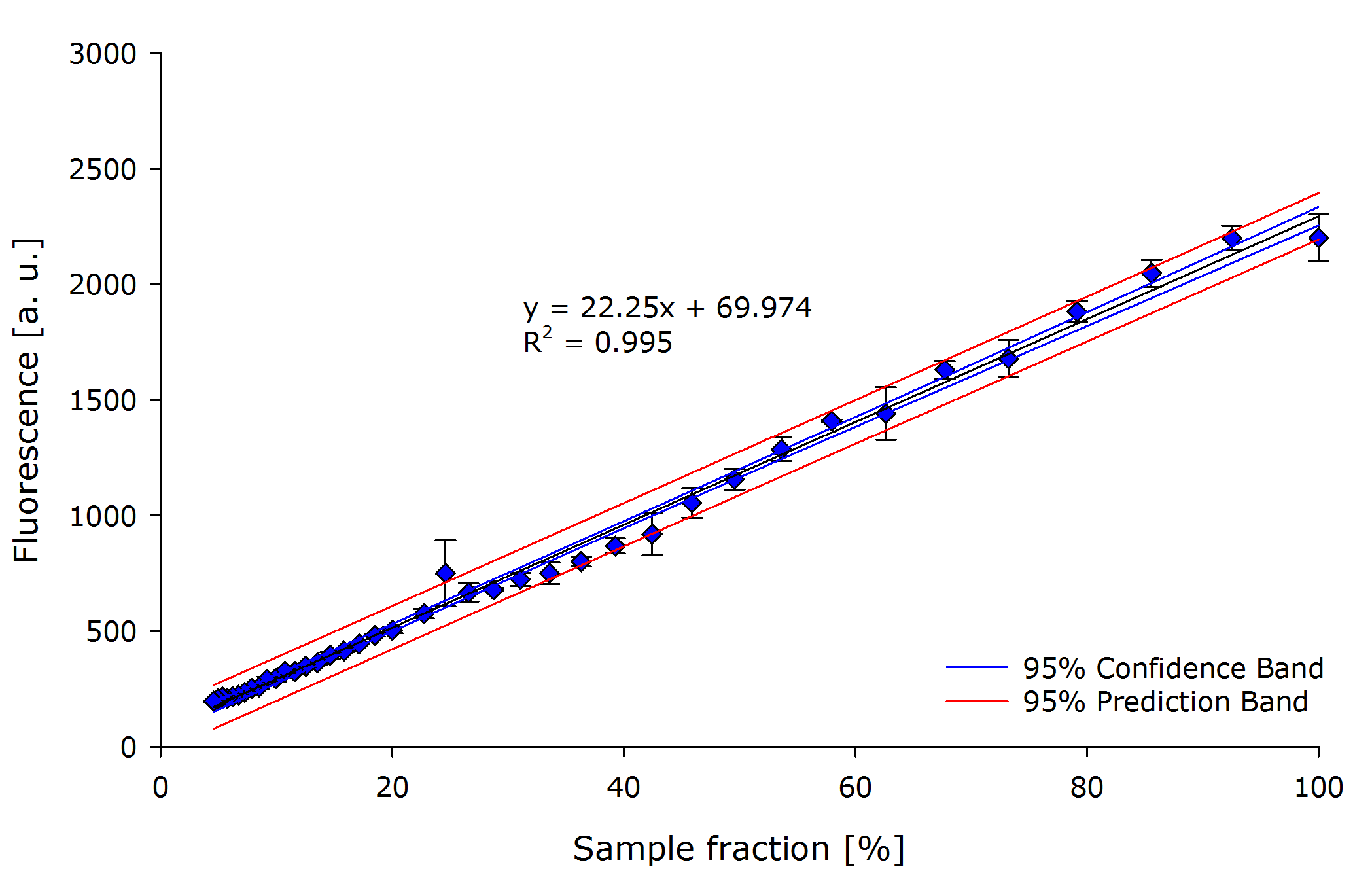

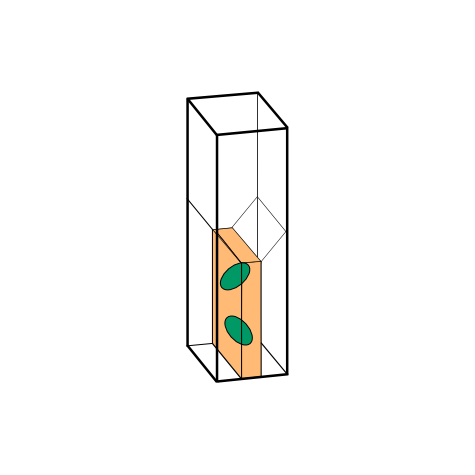

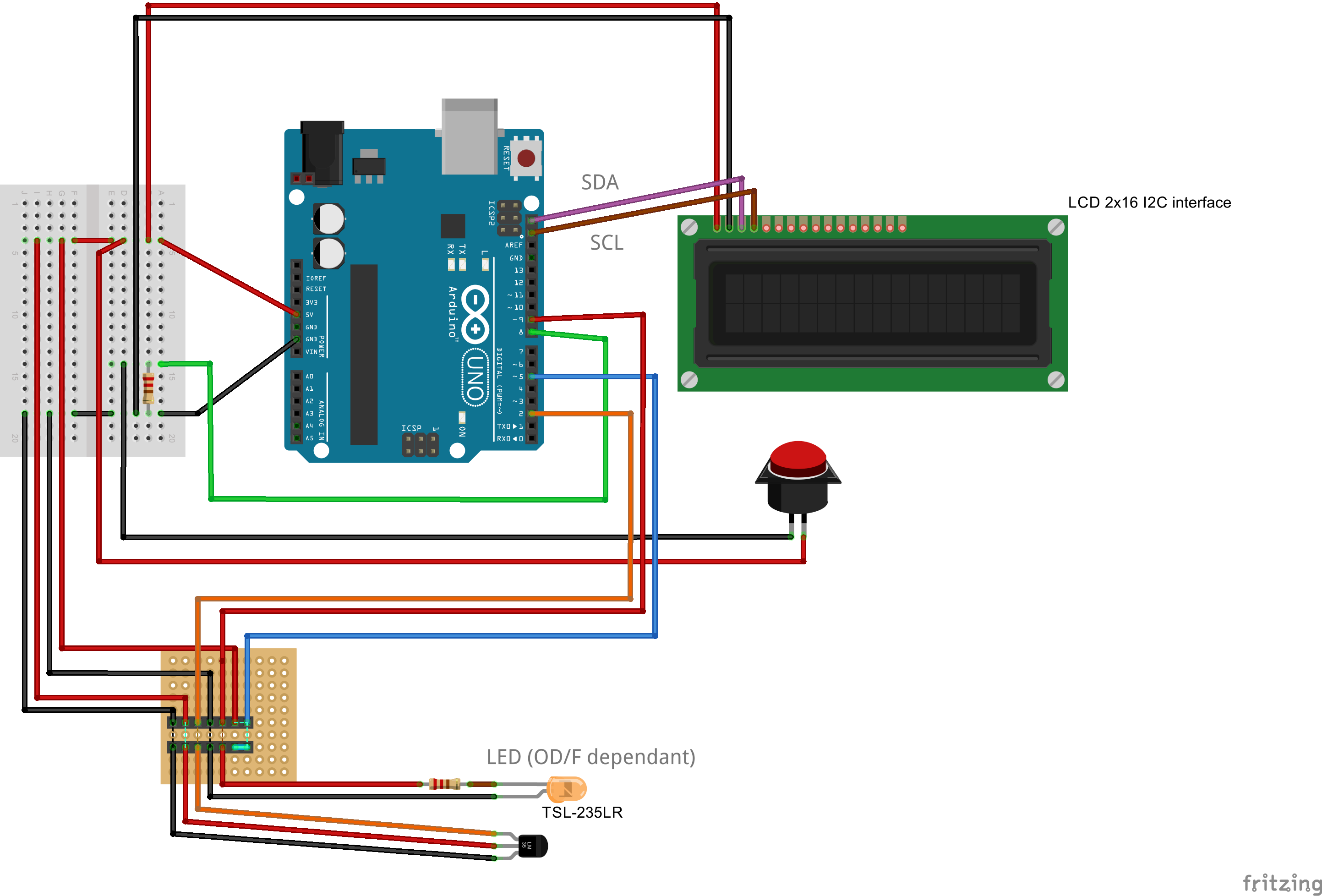

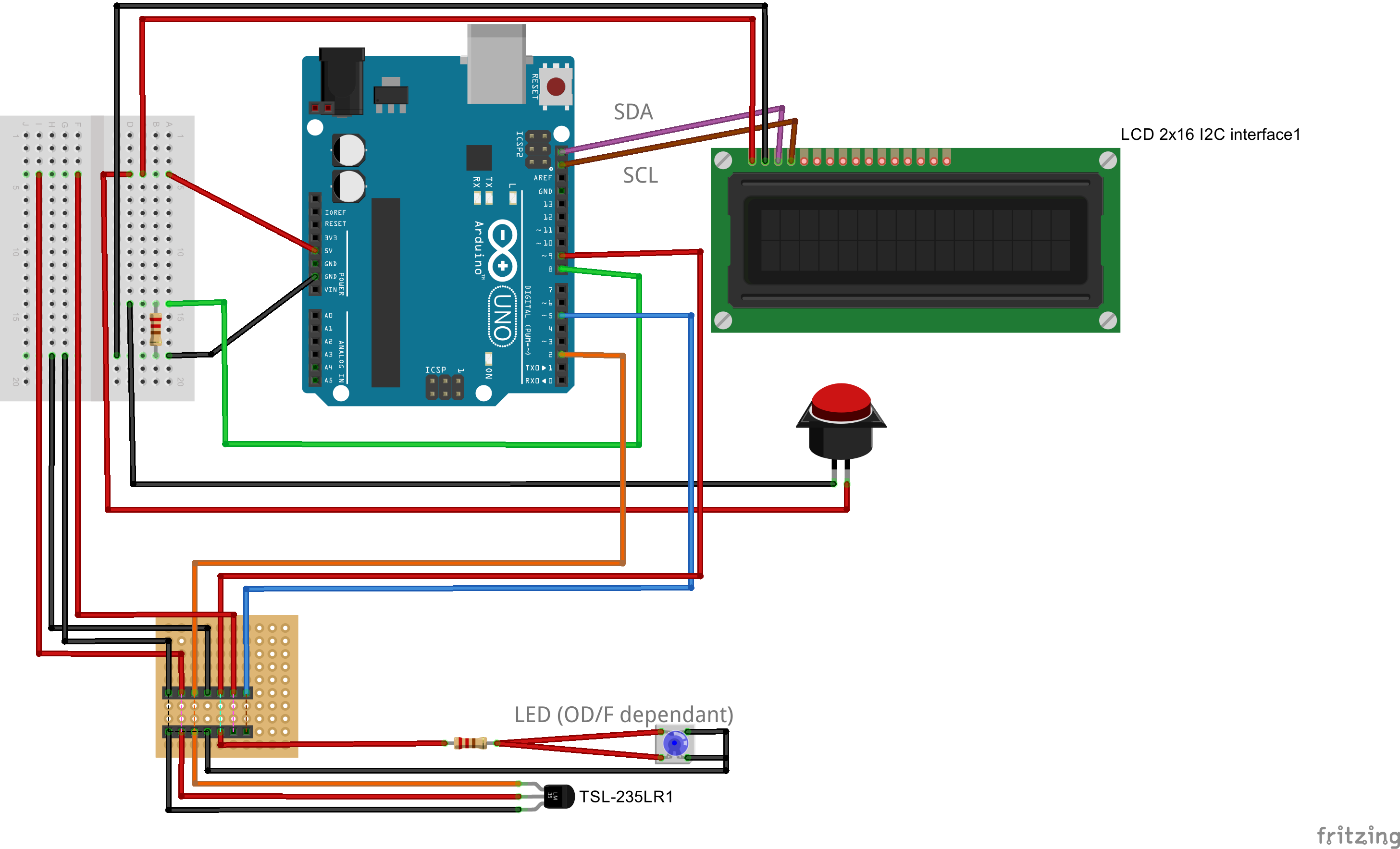

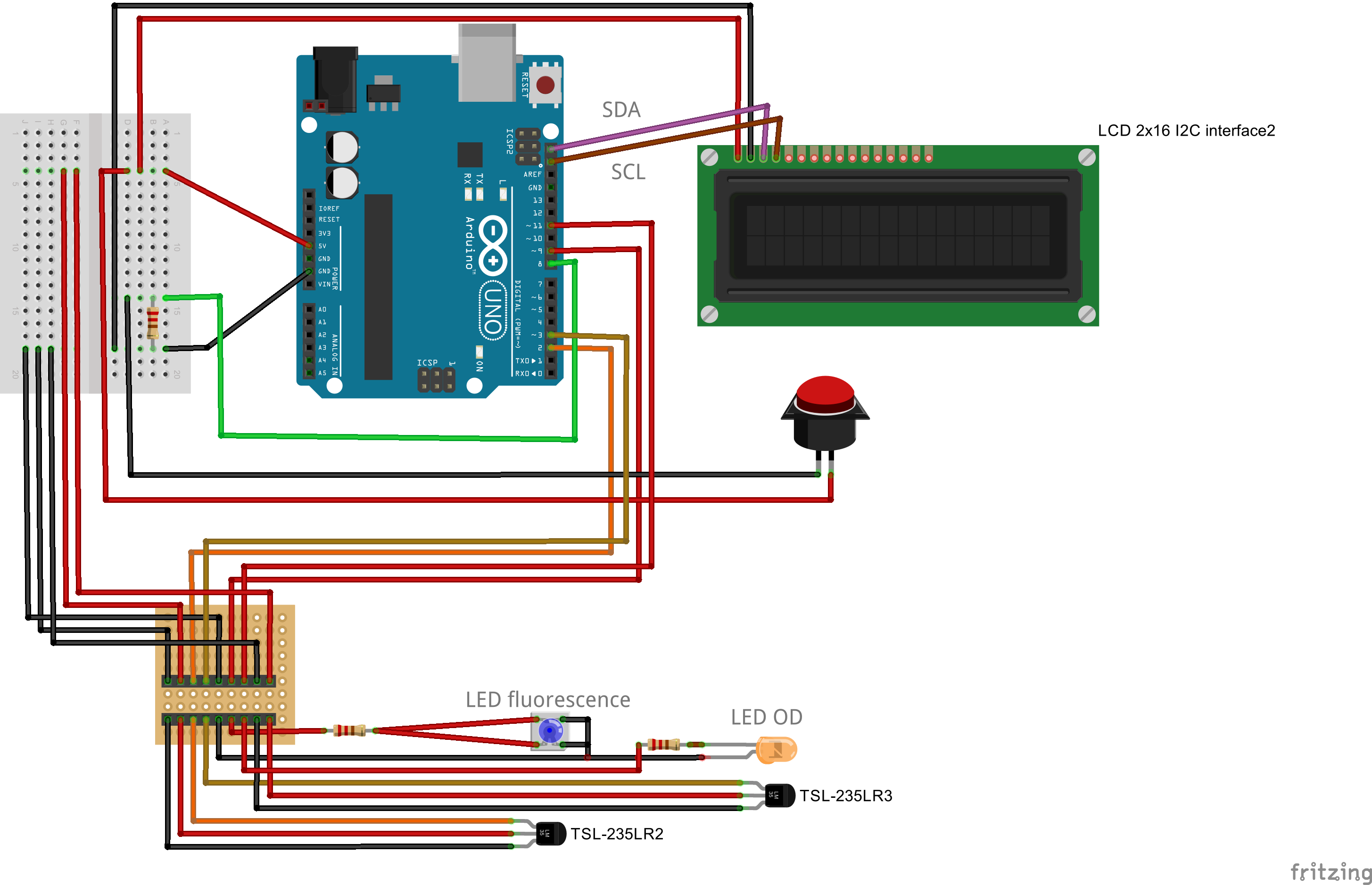

For our OD device we needed to correlate the transmittance measured by our sensor to an optical density anyway.

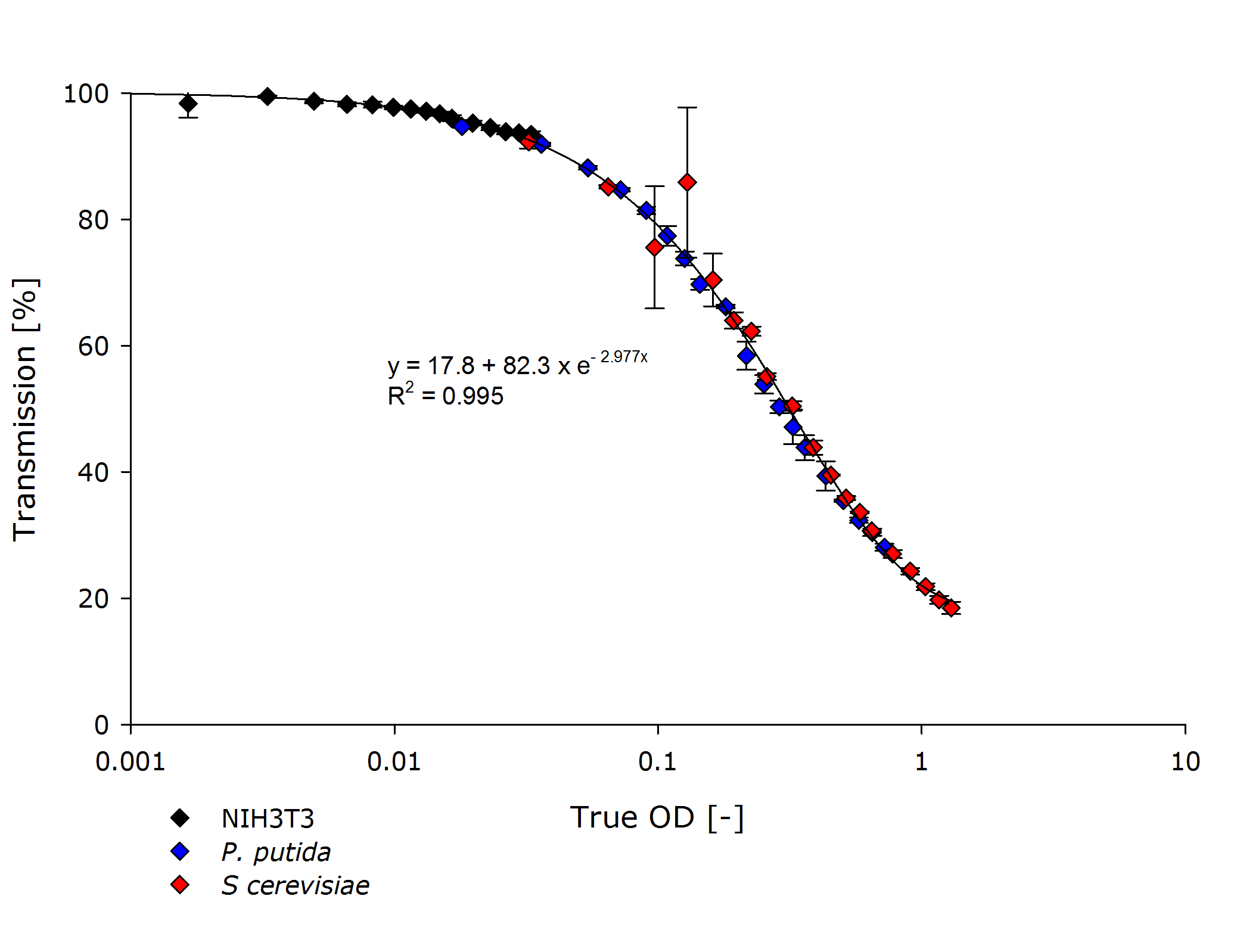

Our team members from the deterministic sciences emphasized on the correction method, which was conducted according to Lawrence and Maier (2006):

- The relative density ($RD$) of each sample in a dilution series is calculated using $\frac{min(dilution)}{dilution}$.

- The uncorrected optical density is derived from the transmission T [%]: $OD = 2 - \log T$

- Finally, the unit optical density is calculated as $\frac{OD}{TD}$.

- The average of the stable unit optical densities is used to calculate the true optical density $ OD_{unit} \cdot RD $.

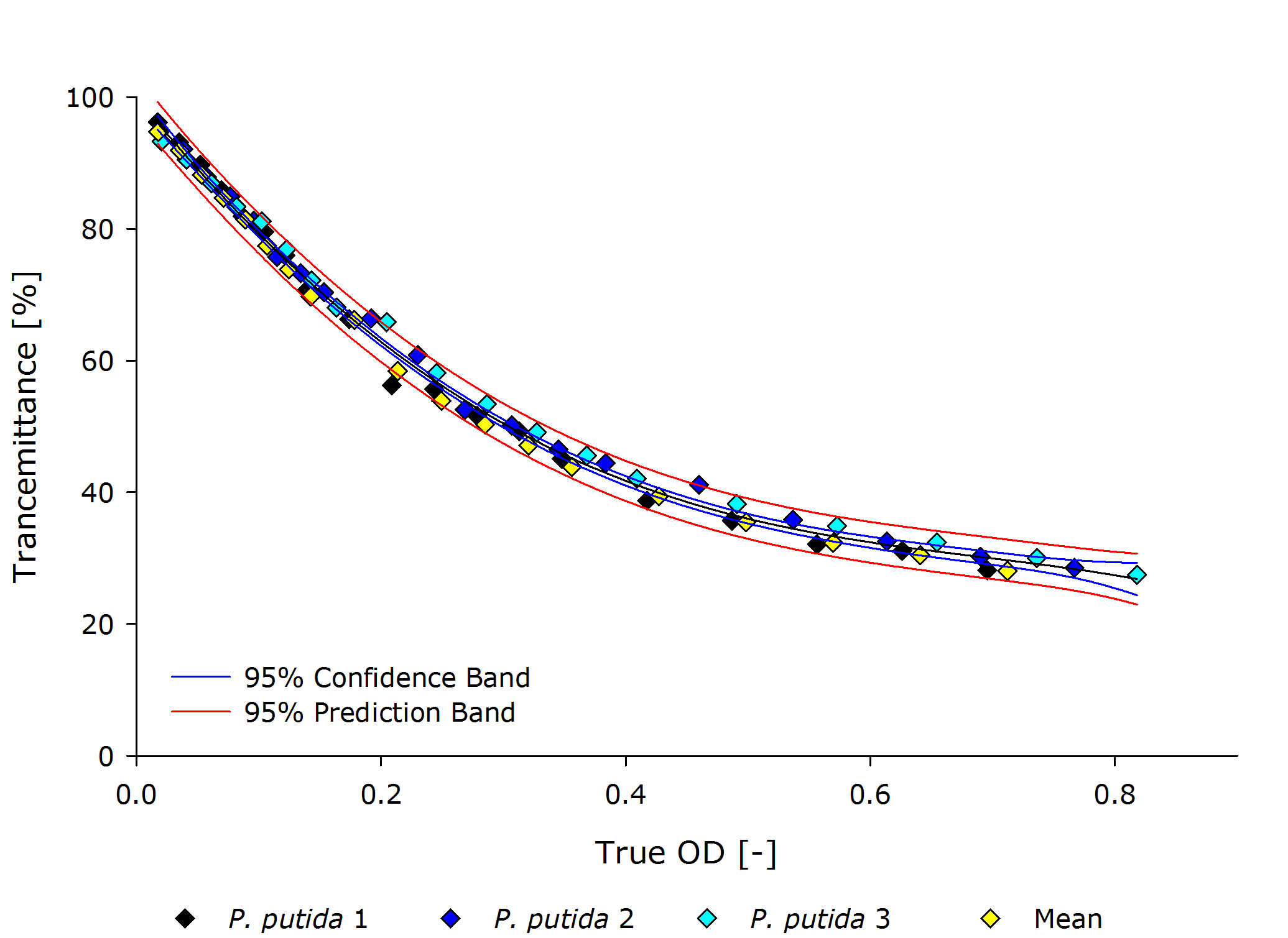

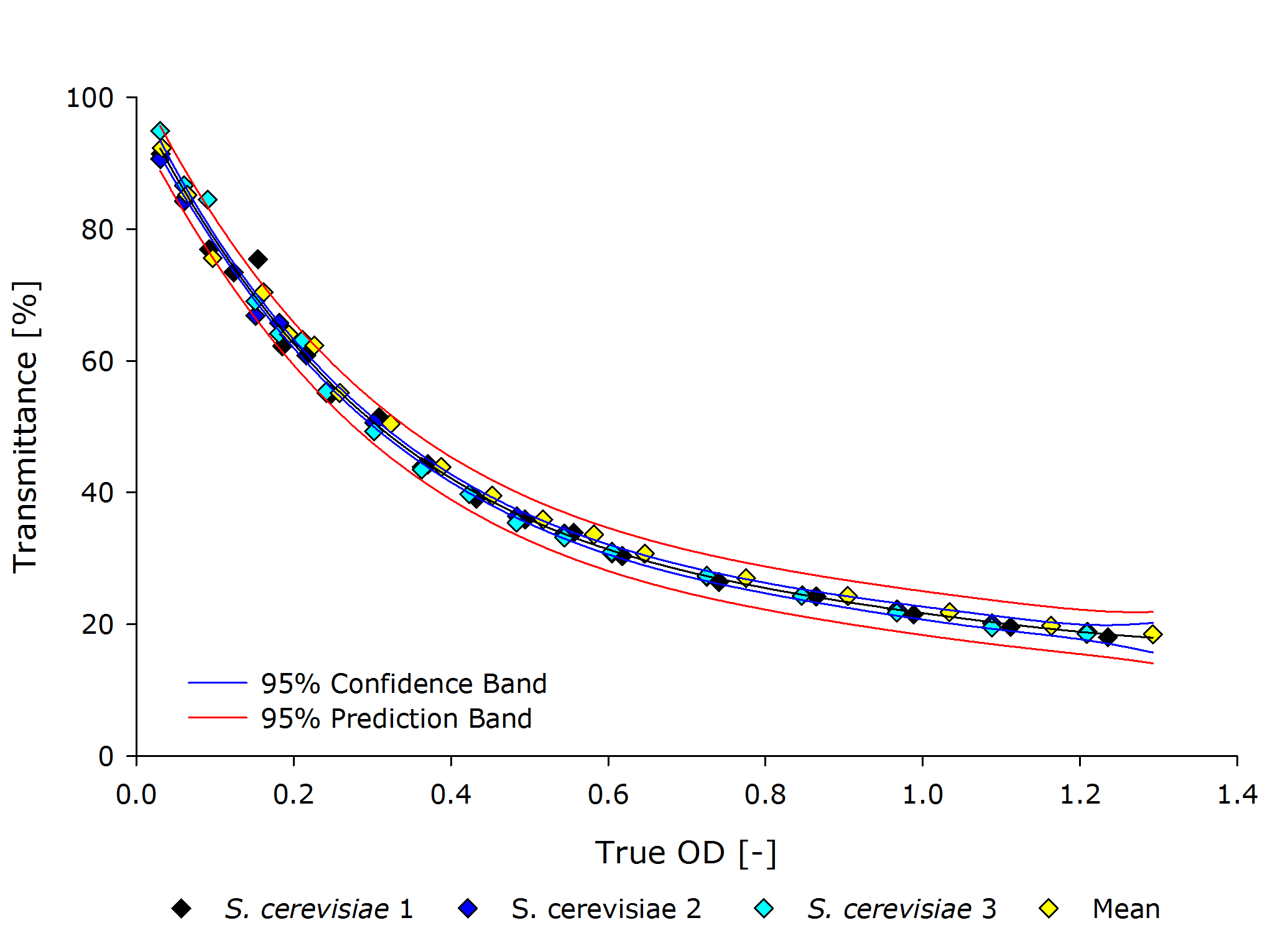

This way, the correlation between transmission and true optical density can be computed.

The derived function allows the conversion from transmission to optical density on our device and therefore calibrates our device.

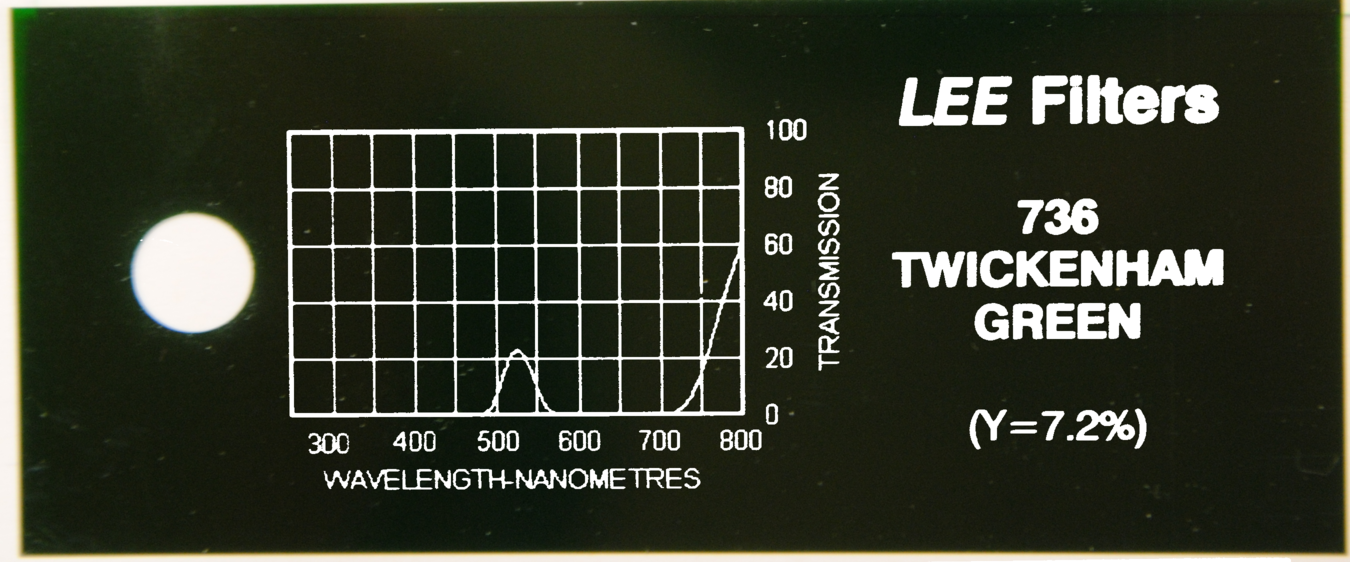

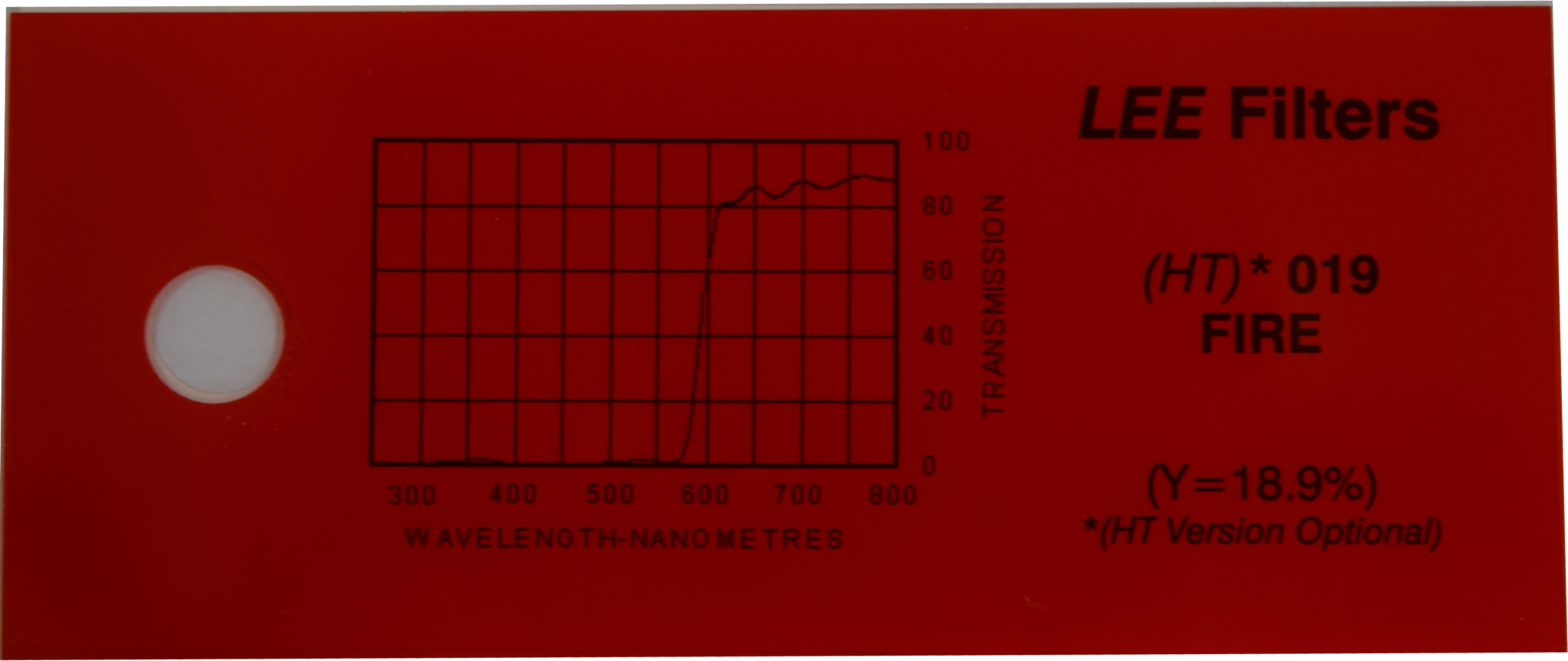

In our experiments, we find in accordance to Lawrence and Maier that the correction majorly depends on the technical equipment used, especially the LED, sensor and cuvettes.

While this at first sight looks disappointing, it is also expected:

Transmittance is the fraction of light not absorbed by some medium relative to the cell-free and clear medium.

However, the transmittance is not only dependent on the amount of cells in the way of the light's beam, but also how much light shines through the cuvette in which fashion, and in which fraction is received by the sensor in which angles.

Using the above formula we performed this experiment for Pseudomonas putida and Saccharomyces cerevisiae and asked team Freiburg to perform the same experiment using mamallian cells.

Experiments

We performed several experiments during the development of the device.

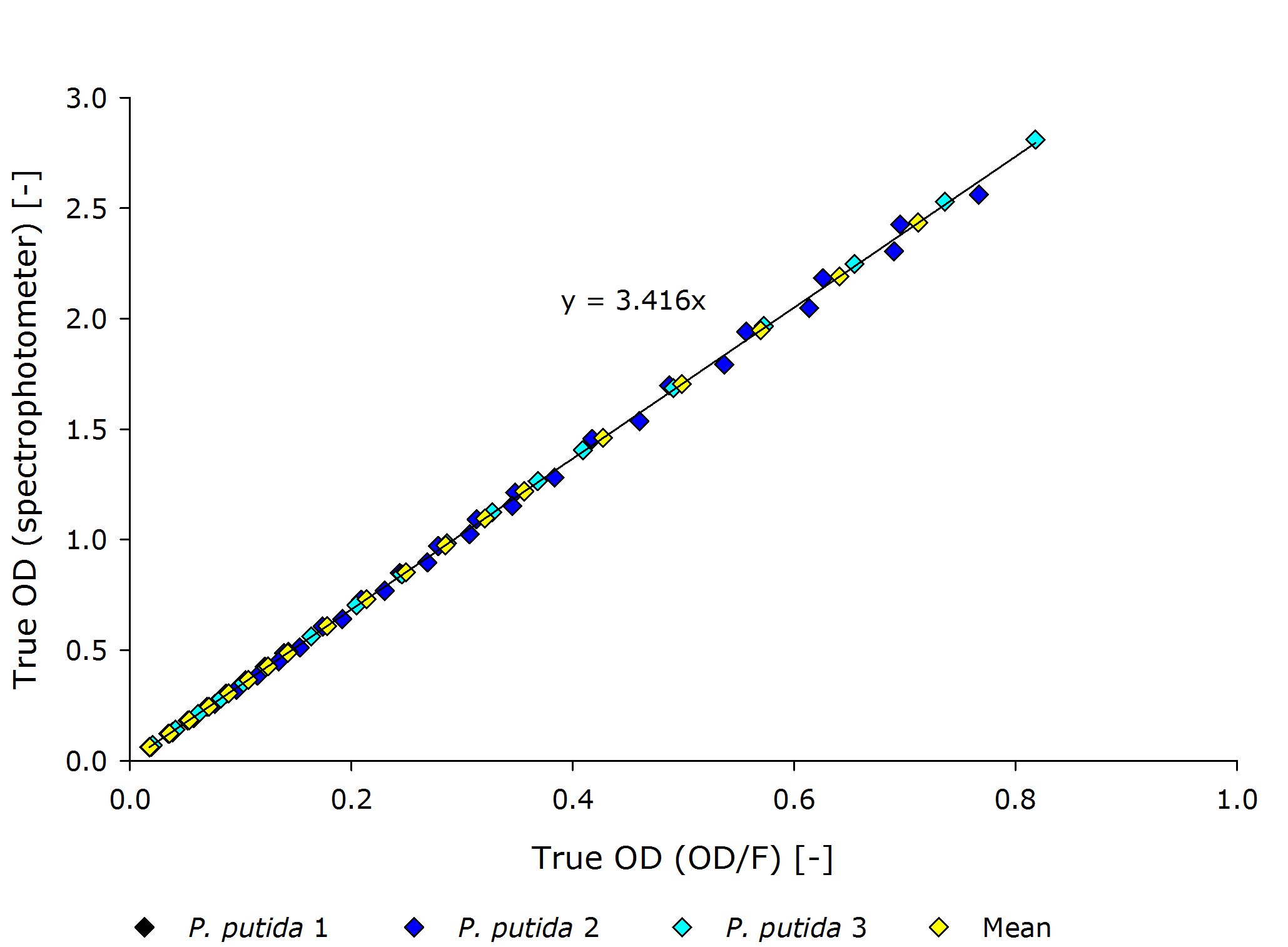

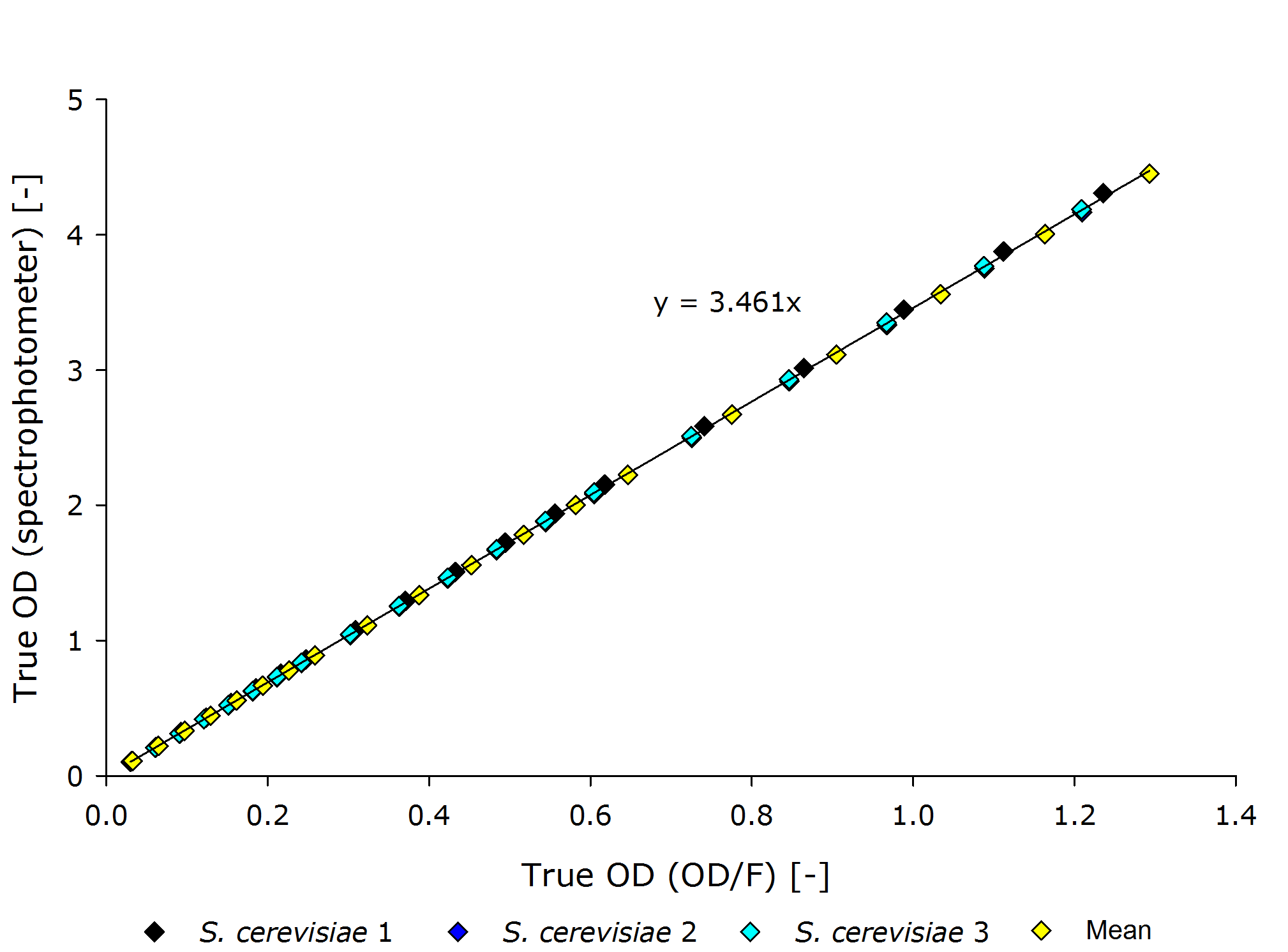

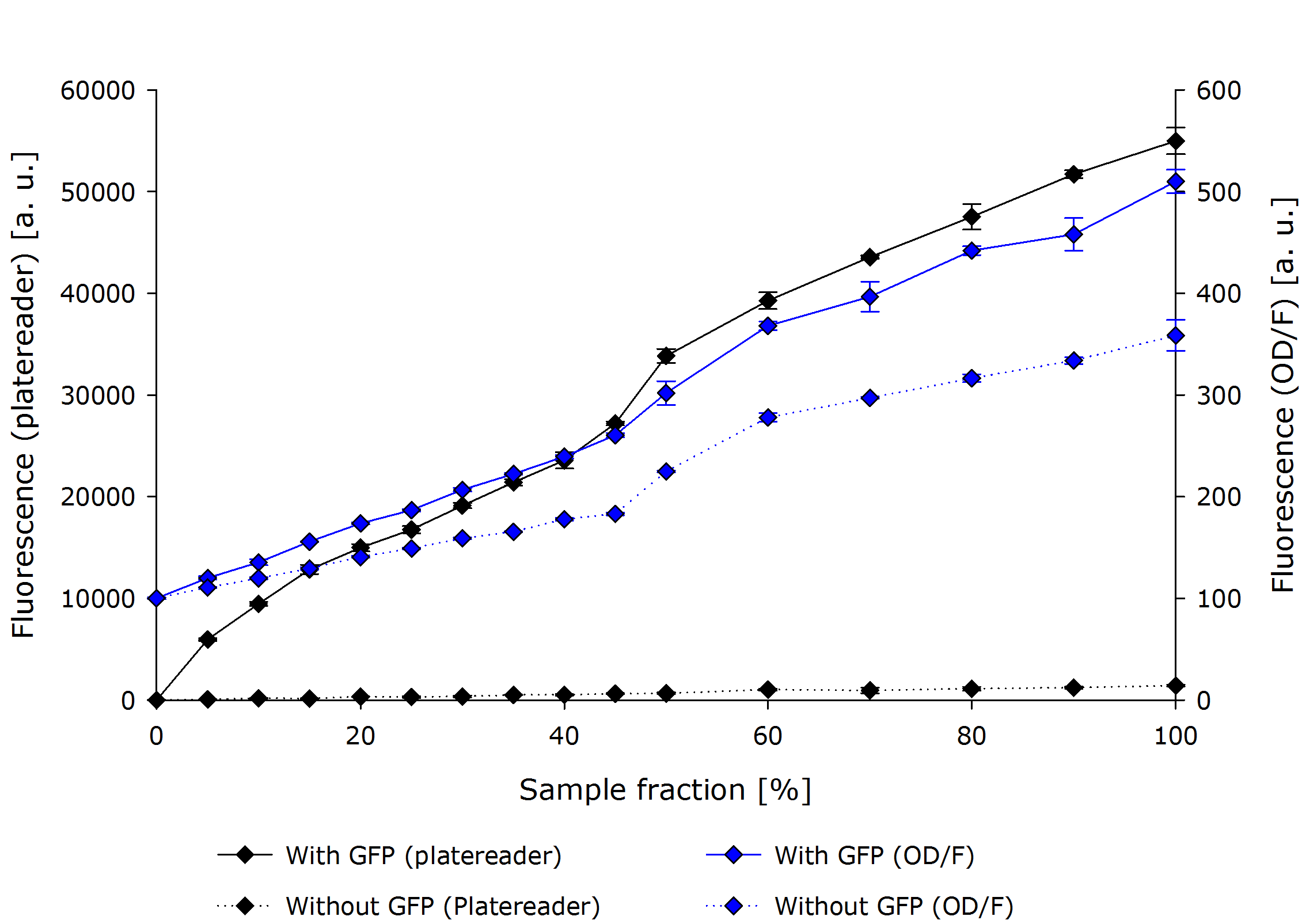

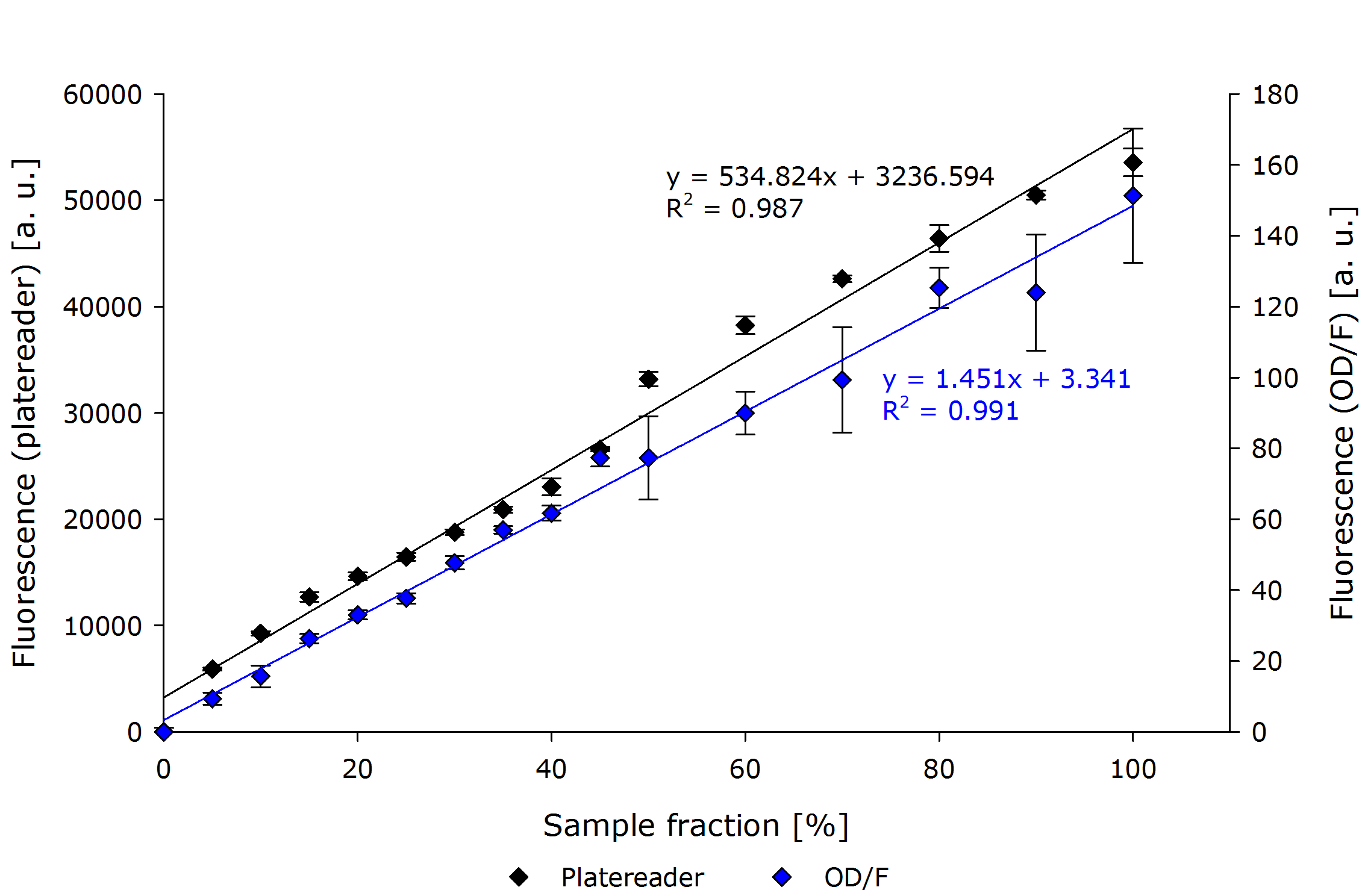

Finally, we can relate the measured transmittance to the true Optical Density (true OD), and further, we can relate the true OD to the true OD of the photospectrometer in our lab.

By doing so, we can calibrate our device to meaningful values.

We have done this according to the previous section for Pseudomonas putida and Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

The final function for calculating the OD from the transmission calculated by our device can be calculated as

$$ OD(T) = f(T) \circ g(device) $$

where $f$ transforms transforms transmittance $T$ to true optical density for our device, and $g$ transforms true optical density of our device into the true optical density of the photospectrometer. This way our device is calibrated according to the photospectrometer.

Pseudomonas putida

Saccharomyces cerevisiae

From these plots, it can be seen that our device delivers robust and reproducible results for both procaryotes and eucaryotes.

Also the function from transmittance to true OD follows a clear pattern, making its calculation possible on a low-end device like a microcontroller.

It is interesting to observer that function $g$, mapping the true OD of our device to the true OD of the photospectrometer, are close together for both P. putida and S. cerivisae, as seen by the regression coefficient.

In fact, 3.416 and 3.461 are such close together, that the minor deviation could be just measuring inaccuracy.

Therefore, we fix the regression coefficient for converting true OD of our device to true OD of the photospectrometer to an average of 3.432 .

Additionally, the function $f$ for mapping transmittance to true OD for our device is similar for all cell types, as seen in the following figure. Therefore the exponential regression curve for all cell types specifies this function.

Finally, we have empirically determined our $OD(T)$ function by finding $f$ and $g$, such that we can convert true OD to the optical density of the photospectrometer.

By this evaluation, we have shown that our self-build OD/F Device can compete with commercial systems.

It is easy to calibrate by just calculating the true optical density.

|

"

"