Team:Heidelberg/pages/Circularization

From 2014.igem.org

Contents |

Introduction

Enzymes represent a major tool for many branches of the chemical industry, including food, brewing, paper, detergent or biofuel. Millions of years of evolution have allowed these proteins to performed extremely specific chemical modifications that are not only essential for living organisms but can also be of great benefit to produce useful molecules for our life, efficiently and at low cost. A major limitation of the use of enzyme for industrial application and in general out of their natural environment is their stability. They can be destroyed by other enzymes and they can unfold and take non-functional conformation when exposed to non-physiological temperature and pH. Such limitations has motivated research in species that can grow at extreme temperatures [1]. Another major area of chemical research is the design of strategies to stabilize enzymes, and more generally proteins and peptides [2][3]. Protein circularization, meaning ligation of the N- and C-terminal ends of a protein, represents a promising way to achieve this stabilization. While conserving the functionality of their linear counterpart, circular proteins can be superior in terms of thermostability [4][5][6], resistance against chemical denaturation [7] and protection from exopeptidases [5][7]. Moreover, a circular backbone can improve in vivo stability of therapeutical proteins and peptides [8]. All these remarkable properties motivated us to develop new tools to circularize any protein of interest. Our Toolbox Guide provides a step-by-step strategy to clone a circularization linker and express it in E. coli. Moreover, in case of complex structures where the protein extremities are far from each other, we have developed the software tool CRAUT that will design the appropriate rigid linkers.

Circular Proteins in Nature

![Figure 1) 3D Structure and sequence of the cyclotide katala B1 <a href='https://2014.igem.org/Team:Heidelberg/Toolbox/Circularization#References'>[15]</a>](http://2014.igem.org/wiki/images/3/3c/Heidelberg_half_Cyclotide_structure.jpg)

The terminal amino acids G and N are linked, resulting in a circular backbone. Six cysteine residues form a knot that greatly enhances stability. (source)

A different type of circular peptides, the plant cyclotides, were discovered more recently [10]. Those circular peptides are true proteins, since their linear precursors are produced by ribosomes [9]. The peptide ligase catalyzing the circularization of cyclotides, butelase 1, was discovered a few months ago [11]. Cyclotides are rather small (<79 aa) and most often them are additionally stabilized by disulfide bonds [9]. The first cyclotide to be discovered, katala B1, has been used by African women to accelerate childbirth and was obtained by boiling the dry plant leaves, demonstrating its considerable thermostability [10]. The unique cyclotide framework (Fig 1) is used in the development of drugs against HIV and cancer [12].

Even in primates circular proteins have been discovered. Rhesus θ-defensin-1, found in rhesus macaque leukocytes, is a highly potent antibiotic peptide [13]. In the human genome there is a similar gene that is disrupted by a stop codon. The peptide called retrocyclin was synthesized chemically and it was shown to protect human lymphocytes from HIV-1 infection in vitro [14].

Importantly, naturally occurring circularization of more complex and larger proteins have not yet been described. Considering the benefit that one can expect from such a modification, we anticipated that developing tools to circularize proteins would be of great help for the scientific and industrial communities.

Synthetically Circularized Proteins

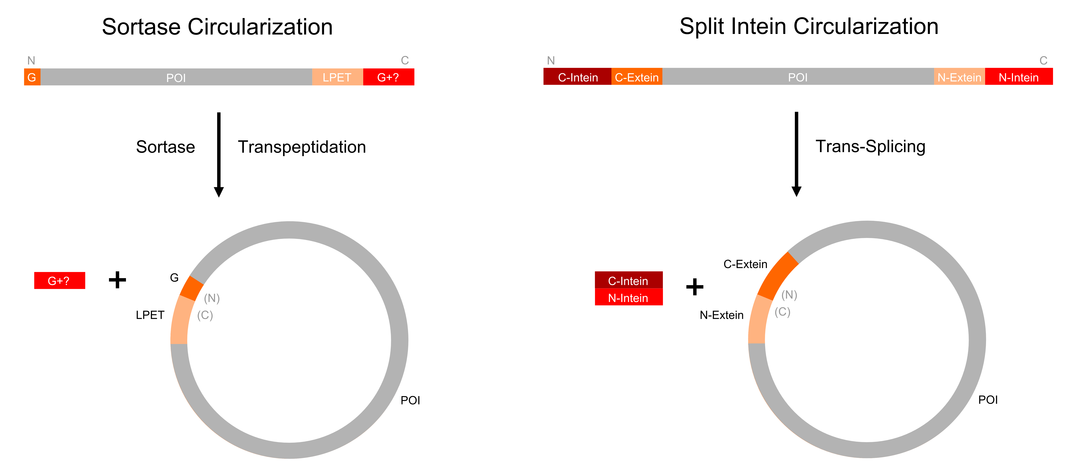

Sortase circularization (left) requires an N-termin G and the sorting signal LPXTG. In a transpeptidation reaction, the sortase reversibly circularizes the backbone. Split intein circularization (left) requires the fusion of split inteins to the termini of the protein of interest. They assemble, cleave out themselves and join the exteins. This process is called protein trans-splicing.

The properties that enzymes may acquire after circularization have motivated many studies that designed strategies to artificially achieve it [16][17]. These strategies followed two different directions: the use of chemistry and the use of biological tools. Here, we focused on the latter ones, and especially two of them: inteins and sortase. The best-researched method to circularize large proteins is based on artificially split inteins. Inteins are integrated as extraneous polypeptide sequences into proteins of interest. They do not contribute to the original protein function but perform an autocatalytic splicing reaction after protein translation. By Analogy to intron splicing on RNA level, this post translational modification was named intein splicing. The protein segments were called intein for internal protein sequence, and extein for external protein sequence, with upstream and downstram exteins termed N-exteins and C-exteins, respectively. Inteins excise themselves out of the host protein while reconnecting the remaining N and C exteins, via a new peptide bond. Interestingly, the host protein maintains its normal structure and function after splicing. [18].

Some inteins like Npu DnaE are naturally split in two fragments, which can reassemble to to the active intein and thus ligate the exteins [19]. This process is called protein trans-splicing. If corresponding split inteins are added to both termini of a protein as illustrated in figure 2), the trans-splicing reaction results in a circular backbone.

Several proteins were circularized using split inteins as a proof of principle, such as dihydrofolate reductase [4] and GFP [7]. In these cases, The proteins were rather small and their termini were in close proximity. Both circular dihydrofolate reductase and GFP showed enhanced resistance against proteases and denaturation. The largest published circularized protein is maltose-binding protein (MBP) (395 aa) from E. coli [20]. However, stability was not tested in this case.

Another interesting approach to circularize proteins is based on sortases [21]. Naturally, sortases catalyze the linkage of surface proteins to the peptides in peptidoglycan precursors. The sortase cleaves proteins after a specific sorting signal and forms an acyl enzyme intermediate, which is susceptible to a nucleophilic attack by amino groups, resulting in a transpeptidation [22]. The attacking nucleophile is not necessarily a pentaglycine of the peptidoglycan, and can also be any N-terminal glycine. As shown in figure 2), sortases can be used to circularize the backbone proteins containing a both sorting signal and a glycine at the N-terminus [21]. As a proof of principle, a GFP variant with an N-terminal polyglycine and LPETG-His6 at the C-terminus was circularized in vitro using sortase A. In this case, faster recovery of fluorescence after denaturation was observed in comparison with a linear control [21].

Our Circularization Project

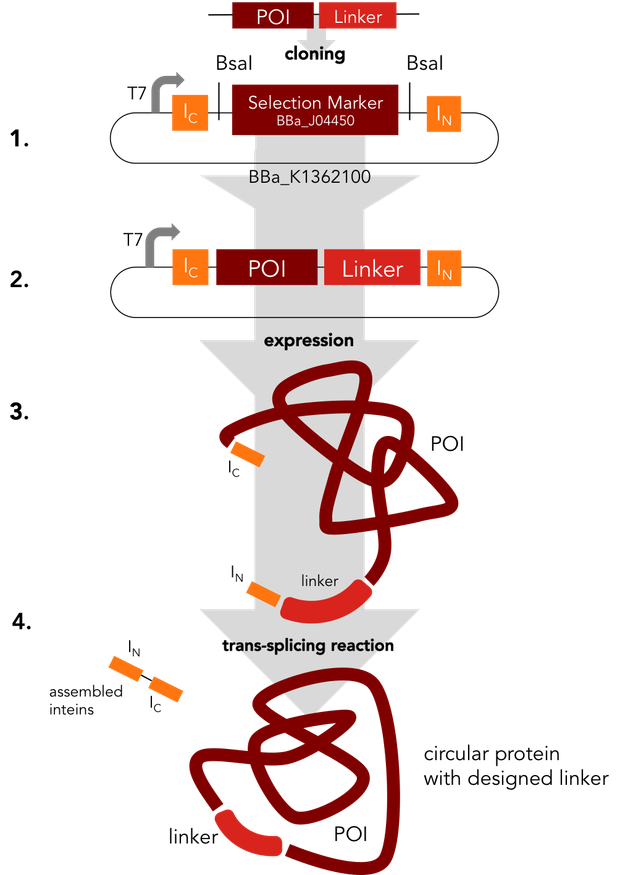

In a single step the protein of interest is cloned into the split intein circularization construct (1.). The resulting plasmid (2.) can be used to express a fusion protein (3.). In an autocatalytic in vivo reaction, the circular protein (4.) is formed.

We decided to standardize the cloning process that is necessary to express circular proteins. Several circularization constructs based on the split intein Npu DnaE and Sortase A were designed. By Golden Gate cloning an mRFP selection marker can easily be exchanged with the protein to be circularized. Using our [http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1362000 split intein circularization construct], a fusion protein of the C-intein, the protein to be circularized and the N-intein is created. Upon expression, the C- and the N-intein assemble and catalyze their own excision and the formation of a peptide bond circularizing the protein. Our Sortase A based construct adds TEV and Sortase A recognition sites to the protein to be circularized. The expressed protein has to be purified and treated with TEV protease and Sortase A to be circularized in vitro. We used GFP to test both split intein and sortase circularization.

The Impact of Circularization on Thermostability

Backbone circularization of proteins increases the thermostability of a protein in a similar way to the introduction of disulfide bridges. Either way, a covalent linkage is introduced that decreases the entropy of the unfolded state of the protein [1]. This principle has already been shown in 1956 in the context of fibrous proteins with covalent linkages [6]. A short explanation of "the entropy of the unfolded state is decreased": an unfolded linear polypeptide can move around, since each angle between the peptide bonds can adopt any possible state. If the polypeptide is circular, the state of those angles is much more restricted. Consequently, an unfolded state is less likely to occur, resulting in a higher thermostability.

Another factor that might improve thermostability is the fixation of the termini. They are usually flexible and thus a possible starting point of the denaturation process [1]. Especially if the termini are close together or a rigid linker is used to join them, this should cause an additional increase of thermostability.

Why introducing circularization to iGEM?

Many iGEM projects deal with industrially or medically oriented applications, which would greatly benefit from having “super” proteins that can handle better the conditions under which they are requested to work. Therefore we thought that circularization was a perfect new tool for iGEM, being all the while very innovative and original in concept. Because we were fascinated by the power of inteins beyond circularization, we decided to expand our project and to create a toolbox that iGEM teams can use in the future to control their proteins of interest in vivo via post-translational modifications. These other applications of our toolbox – independent of circularization – are more relevant to cell biology projects, which are also often found in iGEM.

References

[1] Vieille, C. & Zeikus, G. J. Hyperthermophilic enzymes: sources, uses, and molecular mechanisms for thermostability. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 65, 1–43 (2001).

[2] Gentilucci, L., De Marco, R., and Cerisoli, L., Chemical modifications designed to improve peptide stability: incorporation of non-natural amino acids, pseudo-peptide bonds, and cyclization. Curr Pharm Des 16 (28), 3185 (2010)

[3] Singh, R. K., Tiwari, M. K., Singh, R., and Lee, J. K., From protein engineering to immobilization: promising strategies for the upgrade of industrial enzymes. Int J Mol Sci 14 (1), 1232 (2013)

[4] Scott, C. P., Abel-Santos, E., Wall, M., Wahnon, D. C. & Benkovic, S. J. Production of cyclic peptides and proteins in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 96, 13638–13643 (1999).

[5] Iwai, H. & Plückthun, A. Circular beta-lactamase: stability enhancement by cyclizing the backbone. FEBS Lett. 459, 166–72 (1999).

[6] Flory, J. & Yol, S. Theory of Elastic Mechanisms in Fibrous Proteins. 715, 5222–5235 (1956)

[7] Iwai, H., Lingel, a & Pluckthun, a. Cyclic green fluorescent protein produced in vivo using an artificially split PI-PfuI intein from Pyrococcus furiosus. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 16548–54 (2001).

[8] Trabi, M. & Craik, D. J. Circular proteins--no end in sight. Trends Biochem. Sci. 27, 132–8 (2002).

[9] Craik, D. J. Chemistry. Seamless proteins tie up their loose ends. Science 311, 1563–4 (2006).

[10] A, P. K. B. et al. Elucidation of the Primary and Three-Dimensional Structure of the Uterotonic. 4147–4158 (1995).

[11] Nguyen, G. K. T. et al. Butelase 1 is an Asx-specific ligase enabling peptide macrocyclization and synthesis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 10, 732–8 (2014).

[12] Henriques, S. T. & Craik, D. J. Cyclotides as templates in drug design. Drug Discov. Today 15, 57–64 (2010).

[13] Tang, Y. A Cyclic Antimicrobial Peptide Produced in Primate Leukocytes by the Ligation of Two Truncated -Defensins. Science (80-. ). 286, 498–502 (1999).

[14] Cole, A. M. et al. Retrocyclin: a primate peptide that protects cells from infection by T- and M-tropic strains of HIV-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99, 1813–8 (2002).

[15] KatalaB1. Cyclotide structure. (2007). at <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cyclotide#mediaviewer/File:Cyclotide_structure.jpg>

[16] Aboye, T. L. and Camarero, J. A., Biological synthesis of circular polypeptides. J Biol Chem 287 (32), 27026 (2012).

[17] Sancheti, H. and Camarero, J. A., "Splicing up" drug discovery. Cell-based expression and screening of genetically-encoded libraries of backbone-cyclized polypeptides. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 61 (11), 908 (2009).

[18] Perler, F. B. et al. Protein splicing elements: inteins and exteins — a definition of terms and recommended nomenclature. Nucleic Acids Res. 22, 1125–1127 (1994).

[19] Zettler, J., Schütz, V. & Mootz, H. D. The naturally split Npu DnaE intein exhibits an extraordinarily high rate in the protein trans-splicing reaction. FEBS Lett. 583, 909–14 (2009).

[20] Evans, T. C. Protein trans-Splicing and Cyclization by a Naturally Split Intein from the dnaE Gene of Synechocystis Species PCC6803. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 9091–9094 (2000).

[21] Antos, J. M. et al. A straight path to circular proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 16028–36 (2009).

[22] Marraffini, L. A., Dedent, A. C., Marraffini, L. A., Dedent, A. C. & Schneewind, O. Sortases and the Art of Anchoring Proteins to the Envelopes of Gram-Positive Bacteria Sortases and the Art of Anchoring Proteins to the Envelopes of Gram-Positive Bacteria. 70, (2006).

"

"