Team:Heidelberg/Modeling/Enzyme Modeling

From 2014.igem.org

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

header-bg=black | header-bg=black | ||

| | | | ||

| - | subtitle= | + | subtitle= modeling of lysozyme activity using enzymatic activity modeling with product inhibition |

| | | | ||

container-style=background-color:white; | container-style=background-color:white; | ||

Revision as of 23:34, 17 October 2014

– modeling of lysozyme activity using enzymatic activity modeling with product inhibition

ABSTRACT

....

Contents |

Abstract

biological replicates more than 1000 curves Product inhibition, 75°C activity, many different things found out. kinetics modeling

Introduction

Enzyme kinetics is a widely studied field in biology. From the derived kinetic parameters one can make many different predictions about the function of a certain enzyme. A commonly used approach for the determination of the enzyme kinetic parameters, is the measurement of the reaction rate in time-dependent manner and with varying substrate concentrations. As this approach would be too laborious to apply in a high throughput manner, we instead decided to record the process curves for each lysozyme.

Using the Lysozyme Assay assays we have obtained over 1000 degradation curves for different lysozyme variants and attempted to make predictions about the thermal stability of the different enzymes (REF). For nearly all of the 9 different lysozymes not only two biological replicates from independent culture preparations but also at least 4 technical replicates were measured at certain temperatures the data were measured.

Therefore a comprehensive approach has been made to determine the relevant information, starting with easy fitting of the data and ending with testing of different enzyme kinetics models, evaluation by profile likelihood analysis and in the end identifying the most relevant and robust parameters.

Lysozyme acting on M. lysodeicticus

As described in the linker-screening part, we try to infer the loss of activity of $\lambda$-lysozyme due to heatshock, by observing the kinetic behavior on the degradation of M. lysodeikticus. The process, which ultimately leads to a change of turbidity, is very complex and has been widely discussed for more than 40 years now. On the other hand the activity of lysozyme is highly sensitive to outer conditions like salt concentrations in the media [-1] and the lysozyme concentration itself [0]. We have not only observed the non-enzymatic activity maximum of lysozyme described by Düring et al. [1] but also many observed effects can be explained by applying theory of product inhibition to the kinetics [2]. On the other hand lysozymes unfolding behavior from 37°C seems to be dominated by a rapid collapse when it is denaturated [3].

One of the main problems was that we could not define the amount of enzyme added to the reaction (fig. 1)( plot_of_3_axis2014_10_7_2.png ###Here one can easily see the effect of different enzyme concentrations added to the reaction). The effect of heat inactivation can be observed in (fig 2.) (plot_of_A_axis2014_10_7_2.png Different heatshock temperatures resulting in different kinetic behaviors. One can observe the changes in offset. These we could explain by product inhibition)

Michaelis Menten theory

Michaelis Menten theory describes the catalytical behaviour of enzymes in simple reactions. It's basic reactions are assumed as \[" E + S \, \overset{k_f}{\underset{k_r} \rightleftharpoons} \, ES \, \overset{k_\mathrm{cat}} {\longrightarrow} \, E + P "\] , with E the enzyme, S substrate, ES the enzyme-substrate complex and P the reaction product. $k_r, k_f and k_\mathrm{cat}$ are catalytical constants. This means part of the enzyme is always bound in an enzyme substrate complex. This kinetic behavior can be simplified in the basic differential equation: \[\frac{d\left[S\right]}{dt} = \frac{- V _{max} \left[S\right]}{K_m + \left[S\right]} \]. V_{max} is the maximum reaction velocity, obtained from $V_{max} = k_{cat} * E$ and K_m being the michaelis-menten constant Kompetitive product inhibition has the effect, that part of the Enzyme is also bound in the enzyme-product complex EP. This leads to an apparent increase of $K_m$ as: $K^\text{app}_m=K_m(1+[I]/K_i)$ Thus the differential equation changes as: \[\frac{d\left[S\right]}{dt} = \frac{- V _{max} \left[S\right]}{K_m \left( 1 + \frac{S_0 - S}{k_i} \right) + \left[S\right]} \] where $S_0$ means the substrate concentration at start of the reaction and $k_i$ an inhibitory constant.

Methods

In the beginning of the assays we needed to make certain calibrating measurements so that in the end we could model the enzyme kinetics, minimizing the influence of the measurement process.

Conditions

We established a standard protocol to process the protein mix, that is explained in the Linker_Screening part. It was stressed, that the reaction always took place at the same temperatures. Also another crucial part was the time after adding the enzyme to the substrate. This was minimized as good as possible and we tried to keep it constant. We always made the dilutions in buffer from the same stock, in order to keep salt concentrations fixed.

OD to concentration calibration

There was performed a measurement for calibrating the $OD_{600}$ to substrate concentration. We have seen that until a substrate concentration of 0.66 mg/ml in the 300 µl wells the behaviour is linear with an offset due to the protein mix and the well plate. We have concentrationdifferences result in an $OD_{600}$ difference of: $\delta \mathit{OD} = (1.160 +- 0.004 \frac {\mathtext{ml}} {\mathtext{mg}} * \delta \mathtext{concentration}$. With this result one can easily calculate the concentration differences in each assay. Also the $OD_{600}$ of a well, where all the substrate was completely degraded needed to be measured. We found out, that the influence of the added protein mix on the $OD_{600}$ could be neglected.

Pipeting

One crucial part for the modeling is the time between when lysozyme was added to the substrate and the first measurement in the platereader. This was measured and assumed, that it nearly took the same time for each measurement with normally distributed errors. As the platereader took about 1s for measuring one well, this delay was also taken into account. ###Figure needed, where one can see the time delay###

Controls

We measured degradation curves for two different controls. One was E.coli lysate, processed in the same way as the protein mix, without any lysozyme expressed and the other was only the reaction buffer added to the substrate. We observed some slight decay in $OD_{600}$ in the curves, even if only potassium phosphate buffer was added. Nevertheless the curves of the non-lysozyme containing controls were always clearly distinguishable from samples, where lysozyme was in. Figure distinguish from lysozyme samples

Data

From our linker-screening we got more than 100 000 data points from 12 assays performed on 96 well plates. From each well we obtained the degradation curves of M. lysodeiktikus by lysozyme, measured by turbidimetry change at 600 nm. We tested 8 different constructs of circular lysozyme and as reference also linear lysozyme. For all but two constructs, not only technical replicates on one plate were made, but also biological replicates from different growths. On each plate we subjected the lysozymes a heat-shock for one minute at different temperatures. This led to minimally 4 different curves per biological replicate per temperature and per lysozyme. Each degradation curve consisted in a measurement of the initial substrate concentration withoud lysozyme added, then there is a gap about 2 minutes, varying because of the sequence in that the plate-reader was measuring the wells, and then the degradation was measured every 100 seconds for 100 minutes. The first gap is due to the pipetting step, when adding the enzyme to the substrate and mixing the wells.

PLE analysis

Often when fitting large models to the data there one has the problem that parameters are connected functionally. The method of Profile likelihood estimation enables to reveal of such dependencies. [10] By evaluating the profile likelihood unidentifiable parameters can be grouped into structurally unidentifiable and practically unidentifiable parameters. [9] A parameter is structurally unidentifiable when, it is in a functional dependence of one or more other parameters from the model. It is only practically unidentifiable if the experimental data is not sufficient to identify the parameter. This can be easily distinguished from the profile likelihood. Applying PLE analysis one and identifying structurally unidentifiable parameters, one is able to reduce the complexity of a given model. In our analysis we relied on d2d arFramework, operating on matlab and providing PLE analysis in an easy to use and fast manner.

Final model

For our model of the degradation we decided to apply product inhibited Michaelis Menten kinetics. As all our data was measured in $OD_{600}$ so at first the substrate concentration had to be calculated. Therefore we include an offset turbidity value, that is due to the turbidity of an empty well and included the OD to substrate calibration. Also the initial substrate concentration was inserted. $V_{Max}$, $K_M$, $K_I$ were the three enzymatical parameters that were fitted. Furthermore the error was fitted automatically too. For temperatures higher than 37.0 °C $V_{Max}$ was replaced by a ratio, called the activity of a temperature. Representing how much activity is left, compared to the activity of 37°C. It was defined by: $V^{lysozyme}_{Max, T} = act^{lysozyme}_T V^lysozyme_{Max, 37.0}$. This just meant exchanging one parameter by another for enhanced readability. On the other hand we assumed $K_M$ and $K_I$ to stay the same for different temperatures, but to vary between different lysozyme types. We decided always to fit the data of one plate on it's own, because we observed variation in functional behavior between the measurements from the different days. In table 1 it is shown which parameters are fixed for which part of the model.

| span of a parameter | $K_M$ | $K_I$ | $V_{Max}$ | $k_{decay}$ | OD offset | init_Sub | Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lysozymes | |||||||

| All lysozymes on the same plate | x | ||||||

| Same biological replicates of lysozyme on the same plate | x | x | |||||

| Same biological replicates of lysozyme on the same plate and the same temperature | x | ||||||

| Plate | |||||||

| The same plate | x | ||||||

| All plates | x | x | |||||

Different models tested

During the development of our model, we have tested and compared different models. We tried many models describing the data of all the assays at once. These resulted often in calculations going on for hours. Mainly they were all variations of the final model, always based on product inhibited Michaelis Menten theory. In all the models modeling all the assays, $V_Max$ was split up into $k_{cat} * E$ where k_{cat} would be the same over different biological replicates and different plates, but E could vary.

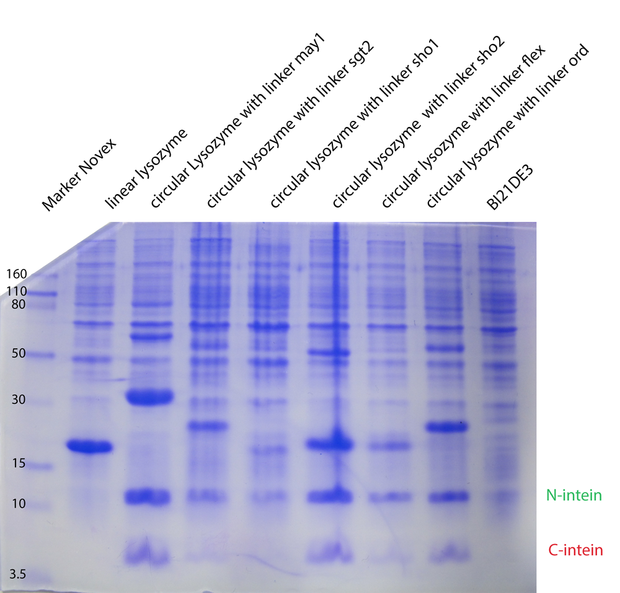

In the second model we have fixed $k_{cat}$ arbitrarily to 1 for all the different enzymes. In the third model we have tried $K_M, K_{cat}, K_I$ were fixed for the different temperatures, varying for the different types of lysozymes. In the next model (4) $K_M, K_{cat}, K_I$ were fitted separately for each temperature and each enzyme type. Substantially different was model 5, where we have inserted ratios for the enzyme concentrations. These ratios were obtained from coomassie gels. Unfortunately no calibration could be made, so we could not introduce concentrations, but just ratios from the different types. For all the models on the whole dataset, the enzyme concentration was fixed between biological replicates.

Model 6 was built to model the kinetics of one single plate. In contrast to the final model, here the kinetic parameters $K_{cat}, K_I$ were fitted for each temperature separately.

Results

We have tested different models to identify the best fitting for our purpose on identifying the decrease in enzyme activity with temperature. All the models could explain the data well. This was checked by looking at a sample of the data plots with the model's predictions. On the other hand the identifiability of the different parameter was checked by PLE analysis, after fitting the parameters to the models.

Different days-> Freeze thaw, different starting points.

-> product inhibition well described,

-> fixed values because of literature

-> resulting in change of E

-> units on k*E

Figures:

1. Fits, Erklärung, dass unser Modell die Daten gut beschreibt

2. Profile likelihoods

3. Nichtidentifizierbarkeit von Parametern

4. Unsere interessanten Parameter

5 Leitmotive: Was wurde gemacht, warum wurde gemacht, wie wurde gemacht (kurz) Was ist rausgekommen.

resultsofscreening.png resultsaverageofscreening.png

Conclusion

The parameters that were interesting for us, were the decays in $V_{Max}$ with temperature of heat-shock. These were all identifiable for each plate.

Gels to fix enzyme concentration, and biological replicates -> kcat

Add from the beginning in different amounts -> $K_I$

Higher substrate concentrations -> $K_M$

The long way to the model

For long time we have thought it would be easy to extract the relevant data out of our lysozyme assays. But this though somehow perished one week before wiki freeze. For showing that science is always trying and failing, we wanted to explain how we came up with the upper model in the next part.

First try, easy fitting

The first thought when looking to the curves was that the reaction was clearly exponentially with some basal substrate decay and a small offset due to the different types of proteinmix added. The relevant parameter for us would be only the exponente which would be equal to some constant k times the enzyme concentration present. We would assume, that the constant doesn't change after heatshock, but the part of enzyme that survived. This assumption is based on a paper by Di Paolo et al., who claim that for pH denaturation of $\lambda$-lysozyme there are only two transition states, folded and unfolded. [3] This way curves for the temperature decay can be measured for each kind of lysozyme and finally compared to each other.

A basic problem of this method was, that it could never be excluded, that the temperature behaviour is not due to some initial concentration effects and that is why we chose to try Michaelis menten fitting, as in a perfect case, one could make an estimation on the amount of enzyme in the sample. As the exponential is just a special case of Michaelis Menten, one can always enlarge the model with this contribution.

Fitting Michaelis-Menten kinetics to the concentration data

As we are screening different lysozymes in high-throughput we tried to use the whole data obtained from substrate degredation over time by applying integrated michaelis menten equation [4] But as there is always an OD shift because of the plate and the cells lysate we need to take this parameter into account while fitting.

The basic differential equation for Michaelis-Menten kinetics [5] is:

\[\frac{d\left[S\right]}{dt} = \frac{- V _{max} \left[S\right]}{K_m + \left[S\right]} \]

Where $\left[S\right]$ means substrate concentration at time 0 or t respectively, $ V _{max}$ is the maximum enzyme reaction velocity, $K_m$ is Michaelis-Menten constant and t is time. This leads to:

\[ \frac{K_m + \left[S\right]}{\left[S\right]} \frac{d\left[S\right]}{dt} = -V_{max}\]

Which we can now solve by separation of variables and integration.

\[ \int_{\left[S\right]_0}^{\left[S\right]_t} \left(\frac{K_m }{\left[S\right]} + 1\right) d\left[S\right] = \int_{0}^{t}-V_{max} dt'\]

This leads to,

\[K_m \ln\left( \frac{\left[S\right]_t}{\left[S\right]_0} \right) + \left[S\right]_t - \left[S\right]_0 = -V_{max} t \]

what we reform to a closed functional behaviour of time.

\[t = - \frac{K_m \ln\left( \frac{\left[S\right]_t}{\left[S\right]_0} \right) + \left[S\right]_t - \left[S\right]_0 } {V_{max}} \]

As the functional behaviour is monotonous we can just fit this function to our data, which should directly provide us with $V_max$ which is the interesting parameter for us.

As OD in the range where we are measuring still is in the linear scope with some offset due to measurement circumstances and the absorption of the cells lysate we can use $\left[S\right] = m OD + a$, where a is the offset optical density, when all the substrate has been degraded, OD is the optical density at 600 nm and m is some parameter that needs to be calibrated.

So we can refine the functional behaviour as:

\[t = - \frac{K_m \ln\left( \frac{ m ({\mathit{OD}}_t - a)}{ m (\mathit{OD}_0 - a)} \right) + m \mathit{OD}_t - m \mathit{OD}_0 } {V_{max}} \]

$OD_0$ is just the first measured OD we get, this parameter is not fitted.

But these fits did completely not converge so we needed to find another solution. Liao et al. proposed and compared different techniques for fitting integrated Michaelis-Menten kinetics, [7] which didn't work out for us, because starting substrate concentration was too low for us and thus the fits converged to negative $K_m$ and $V_Max$. Finally we fitted Michaelis-Menten kinetics using the method proposed by Goudar et al. [6] by directly fit the numerically solved equation, using lambert's $\omega$ function, which is the solution to the equation $ \omega (x) \exp (\omega(x)) = x$. So we fitted

\[ \left[S\right]_t = K_m \omega \left[ \left( \left[A\right]_0 / K_m \right) \exp \left( \left[A\right]_0 / K_m -V_{max} t / K_m \right) \right] \]

This worked well, the fits converged reliably, but sometimes produced huge errors for $K_m$ and $V_Max$ of the order of $10^5$ higher than the best fit for these values. This simply meant, that from most data, these parameters could not be identified. On the other hand simple exponential fit reproduced the data nearly perfectly, which made us concluding, that we're just working in the exponential regime, because $K_m$ is just much too high for the substrate concentrations we're working with, so that the differential equation from the beginning ###link### would transform into:

\[\frac{d\left[S\right]}{dt} = - V _{max} \left[S\right] \]

which is solved by a simple exponential equation

\[ \left[S\right]_{t} = \left[S\right]_0 e^{\left( - V_{max} t \right)} \]

As we're measuring OD function fitted to the data results in:

\[ \mathit{OD}_{t} = \left(\mathit{OD}_0 - a\right) e^{\left( - V_{max} t \right)} + a \]

with a a parameter for the offset in OD due to the plate and the proteinmix.

This method seemed to be the method of choice, as it also produced nice results. We have written a python skript [ ???Link???] that handled all the data, the plotting and the fitting and in the end produced plots with activities normalized to the 37°C activity. These results though had too large errorbars, so we tried to set up a framework to fit multiple datasets in one, with different parameters applied to different datasets. We chose to work with the widely used d2d arFramework developed by Andreas Raue [8] running on MATLAB. As all the datahandling had already happened in python we appended the script with the generation of work for the d2d framework, so that our huge datasets could be fitted at once. The fitting worked out quite well, but some strange results could not be explained yet with that.

Modeling product inhibition

We observed many different phenomena we could not explain properly. For example when the activity at 37°C started low, it seemed, that the protein doesn't loose it's activity after heatshock ###figure needed###. This meant that there was some kind of basal activity, independent of the enzyme concentration. On the other hand activity was not completely linear to enzyme concentration. But the most inexplicable part was, that some samples even after 1h of degradation stayed constant at an $OD_{600}$ level, nearly as high as the starting $OD_{600}$. This could only be due to the substrate not being degraded, so we checked this by adding fresh lysozyme to the substrate. We observed another decay in $OD_{600}$, which clearly meant, that not the substrate ran out, but the enzyme somehow lost activity during measurement. This meant, that our basic assumption from above was completely wrong and the results completely worthless, as we are only detecting a region of the kinetics, where already some enzyme has been lost due to inhibition. But therefore nothing about initial enzyme concentration in the sample could be said. We even found this based in a paper from 1961 written in french [2].

Grand model

We then tried to always fit one grand model to all the data we have obtained from all the different assays, with curves for different temperatures, biological replicates and technical replicates. In total these were about 100 000 data points we feeded in and up to 500 parameters we fitted. This did not work out, because the variation in starting amounts of enzyme was too large even between the technical replicates from different days. This might be due to the freeze thaw cycles, that the enzyme stock was subdued to. On the other hand this model was just way too complex to be handled easily, as it took hours only for the initial fits. Calculating the profile likelihoods took about one day. Therefore we chose to take another approach, always modeling the data of one single plate, as on that for sure the variations were much less. Of course thus different parameters would not be identifiable, for example the enzyme concentration would not be comparable between the different samples. On the other hand, the only parameters, that are interesting for our purpose, the bahavior after heatshock would still be identifiable.

References

[-1] Mörsky, P. Turbidimetric determination of lysozyme with Micrococcus lysodeikticus cells: reexamination of reaction conditions. Analytical biochemistry 128, 77-85 (1983).

[0] Friedberg, I. & Avigad G. High lysozyme concentration and lysis of Micrococcus lysodeikticus, Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 127 (1966) 532-535

[1] Düring, K., Porsch, P., Mahn, A., Brinkmann, O. & Gieffers, W. The non-enzymatic microbicidal activity of lysozymes. FEBS Letters 449, 93-100 (1999).

[2] Colobert, L. & Dirheimer G. Action du lysozyme sur un substrat glycopeptidique isolé du micrococcus lysodeiktikus. B1OCHIMICA ET BIOPHYSICA ACTA, 54, 455-468 (1961)

[3] Di Paolo, A., Balbeur, D., De Pauw, E., Redfield, C. & Matagne, A. Rapid collapse into a molten globule is followed by simple two-state kinetics in the folding of lysozyme from bacteriophage λ. Biochemistry 49, 8646-8657 (2010).

[4] Hommes, F. A. "The integrated Michaelis-Menten equation." Archives of biochemistry and biophysics 96.1 (1962): 28-31.

[5] Purich, Daniel L. Contemporary Enzyme Kinetics and Mechanism: Reliable Lab Solutions. Academic Press, 2009.

[6] Liao, Fei, et al. "The comparison of the estimation of enzyme kinetic parameters by fitting reaction curve to the integrated Michaelis–Menten rate equations of different predictor variables." Journal of biochemical and biophysical methods 62.1 (2005): 13-24.

[7] Goudar, Chetan T., Jagadeesh R. Sonnad, and Ronald G. Duggleby. "Parameter estimation using a direct solution of the integrated Michaelis-Menten equation." Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Protein Structure and Molecular Enzymology 1429.2 (1999): 377-383.

[8] Raue, A. et al. Lessons Learned from Quantitative Dynamical Modeling in Systems Biology. PLoS ONE 8, (2013).

[9] Raue, a et al. Structural and practical identifiability analysis of partially observed dynamical models by exploiting the profile likelihood. Bioinformatics 25, 19239 (2009).

[10] Raue, A. et al. Lessons Learned from Quantitative Dynamical Modeling in Systems Biology. PLoS ONE 8, (2013).

"

"