Team:Cornell/project/wetlab

From 2014.igem.org

(Difference between revisions)

| (69 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

$('li.p_wet_over').addClass('active'); | $('li.p_wet_over').addClass('active'); | ||

}); | }); | ||

| - | + | </script> | |

<body> | <body> | ||

<div class="container" id="top"> | <div class="container" id="top"> | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

<div class="col-md-9 col-xs-15"> | <div class="col-md-9 col-xs-15"> | ||

| - | + | <h1>Idea</h1> | |

| - | + | We sought to create genetically engineered strains of <i>E.coli</i> that could sequester the nickel, mercury, and lead from water sources. Each strain included a metal transport protein specific to the respective metal as well as a metallothionein to bind metal ions intracellularly. We first generated basic, functional BioBricks containing: a glutathione-s-transferase gene and yeast metallothionein (<i>crs5</i>) gene fusion for metal binding <a href="http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1460001">(BBa_K1460001)</a>;<sup>[1]</sup> the nickel transport gene <i>nixA</i> for selective nickel uptake <a href="http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1460003">(BBa_K1460003)</a>;<sup>[2]</sup> the mercury transporter genes <i>merT</i> and <i>merP</i> for selective mercury uptake <a href="http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1460004">(BBa_K1460004)</a>;<sup>[3]</sup> and a putative lead transport gene <i>cbp4</i> for selective lead uptake <a href="http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1460005">(BBa_K1460005)</a>.<sup>[4]</sup> | |

| - | + | <br> | |

| + | <br> | ||

| + | To test for sequestration ability of the combined systems, each transport protein in the amp<sup>r</sup> vector pUC57 was co-transformed with the metallothionein fusion in the cm<sup>r</sup> plasmid pSB1C3 and selected for using both markers. These strains are functional equivalents of the BioBricks <a href="http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1460006">BBa_K1460006</a>, <a href="http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1460007">BBa_K1460007</a>, and <a href="http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1460008">BBa_K1460008</a> and were tested for sequestration ability of nickel, mercury, and lead respectively. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In addition, the sequestering strains can placed into fiber reactors to develop functional sequestering filters (see <a href="https://2014.igem.org/Team:Cornell/project/drylab">dry lab)</a>.The idea of utilizing metallothioneins in parallel with metal transporters for sequestration has been studied for mercury and nickel but has never been explored for lead. | ||

| + | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

| - | <div class="col-md-3 col-xs- | + | <div class="col-md-3 col-xs-3"> |

| - | < | + | <a class="thumbnail" data-toggle="lightbox" href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2014/9/91/Protein.PNG"> |

| - | + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2014/9/91/Protein.PNG"> | |

| - | + | </a> | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2014/ | + | |

| - | </ | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

<div class="col-md-12 col-xs-18"> | <div class="col-md-12 col-xs-18"> | ||

| - | + | <h1>Components</h1> | |

| - | + | <center><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2014/8/81/Cornell_componenet_wetlab.png"></center> | |

</div> | </div> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

<div class="col-md-12 col-xs-18"> | <div class="col-md-12 col-xs-18"> | ||

| - | <h1> | + | <h1>Experiments</h1> |

| - | + | The growth rates of the sequestering strain were measured using spectrophotometry. In addition, two methods were used to determine heavy metal sequestration efficiency. <br><br> | |

| - | - | + | <ol> |

| - | - | + | <li> Spectrophotometer was used to analyze and compare the kinetic growth rates of <i>E. coli</i> cultures expressing only the metallothionein protein, only the transporter proteins, both metallothionein and transporter proteins, and just the vector backbone as a control. </li> |

| - | - | + | <ul> |

| - | + | <li>We hypothesized that the control culture would be mildly sensitive to growth in metal-containing media, while the cultures with the transport protein would be more sensitive to growth in metal-containing media due to increased access of the heavy metal to cellular machinery. Finally, bacteria transformed with both the metal transporter and metallothionein protein would be the least sensitive in metal-containing media. Each strain was grown in different heavy metal concentrations.</li> | |

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <li>Sequestration efficiency was measured by growing both the wild type strains as well as sequestering strains in different concentrations of heavy metals. The concentration of heavy metals after growth was measured in two ways: </li> | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li> Nutrient Analysis Lab at Cornell University using ICP-AES</li> | ||

| + | <li> Using green-fluorescent heavy metal indicator Phen Green</li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | </ol> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| - | <div class="row"> | + | <div class = "row"> |

<div class="col-md-12 col-xs-18"> | <div class="col-md-12 col-xs-18"> | ||

| - | <div class=" | + | <h1>Results</h1> |

| - | + | <ol> | |

| - | </ | + | <li>BL21 strains with the <i>merT/merP</i> transporters showed increased sensitivity to mercury concentrations as expected. In addition, in high mercury concentrations, wild type strain growth was inhibited more than sequestration strain growths were inhibited. However, there was no inhibition of growth with wild type BL21 or strains with transporters for lead and nickel even at very high metal concentrations. </li> |

| + | </ol> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-6 col-xs-9"> | ||

| + | <a class="thumbnail" data-toggle="lightbox" href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2014/8/82/Cornell_merTandmerP_growth.png"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2014/8/82/Cornell_merTandmerP_growth.png"> | ||

| + | </a> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-6 col-xs-9"> | ||

| + | <a class="thumbnail" data-toggle="lightbox" href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2014/1/1c/Cornell_merandmet_growth.png"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2014/1/1c/Cornell_merandmet_growth.png"> | ||

| + | </a> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| - | <div class="row"> | + | </div> |

| + | <div class = "row"> | ||

<div class="col-md-12 col-xs-18"> | <div class="col-md-12 col-xs-18"> | ||

| - | + | <ol start = "2"> | |

| - | < | + | <li>When considering cell density, both lead and nickel sequestering strains removed significantly more metal compared to the wild type BL21 strain. The mercury sequestering strain did not remove significantly more metal compared to the wild type strain.</li> |

| + | </ol> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| - | <div class="row"> | + | <div class="row"> |

<div class="col-md-4 col-xs-6"> | <div class="col-md-4 col-xs-6"> | ||

| - | < | + | <a class="thumbnail" data-toggle="lightbox" href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2014/4/42/Cornell_lead2.png"> |

| - | + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2014/4/42/Cornell_lead2.png"> | |

| - | < | + | </a> |

| - | + | <a href="https://2014.igem.org/Team:Cornell/project/wetlab/lead"> | |

| - | + | <button type="button" class="btn btn-default btn-lg center"> | |

| - | + | Lead Data | |

| - | </ | + | </button> |

| - | </ | + | </a> |

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="col-md-4 col-xs-6"> | <div class="col-md-4 col-xs-6"> | ||

| - | < | + | <a class="thumbnail" data-toggle="lightbox" href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2014/f/fb/Cornell_mercury2.png"> |

| - | + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2014/f/fb/Cornell_mercury2.png"> | |

| - | < | + | </a> |

| - | + | <a href="https://2014.igem.org/Team:Cornell/project/wetlab/mercury"> | |

| - | + | <button type="button" class="btn btn-default btn-lg center"> | |

| - | + | Mercury Data | |

| - | </ | + | </button> |

| - | </ | + | </a> |

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="col-md-4 col-xs-6"> | <div class="col-md-4 col-xs-6"> | ||

| - | < | + | <a class="thumbnail" data-toggle="lightbox" href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2014/3/3a/Cornell_Nickel2.png"> |

| - | + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2014/3/3a/Cornell_Nickel2.png"> | |

| - | < | + | </a> |

| - | + | <a href="https://2014.igem.org/Team:Cornell/project/wetlab/nickel"> | |

| - | + | <button type="button" class="btn btn-default btn-lg center"> | |

| - | + | Nickel Data | |

| - | </ | + | </button> |

| - | </ | + | </a> |

</div> | </div> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

<div class="col-md-12 col-xs-18"> | <div class="col-md-12 col-xs-18"> | ||

<h1 style="margin-bottom: 0px">References</h1> | <h1 style="margin-bottom: 0px">References</h1> | ||

<hr> | <hr> | ||

<ol> | <ol> | ||

| - | + | <li>Huang, J. et al. Fission yeast HMT1 lowers seed cadmium through phytochelatin-dependent vacuolar sequestration in Arabidopsis. <i>Plant Physiol</i>. 158, 1779–88 (2012).</li> | |

| - | <li> | + | <li>Krishnaswamy, R. & Wilson, D. B. Construction and characterization of an Escherichia coli strain genetically engineered for Ni(II) bioaccumulation. <i>Appl. Environ. Microbiol</i>. 66, 5383–6 (2000).</li> |

| - | <li> | + | <li>Wilson, D. B. Construction and characterization of Escherichia coli genetically engineered for Construction and Characterization of Escherichia coli Genetically Engineered for Bioremediation of Hg 2+ -<i>Contaminated Environments</i>. 2–6 (1997).</li> |

| - | + | <li>Arazi, T., Sunkar, R., Kaplan, B., & Fromm, H. (1999). A tobacco plasma membrane calmodulin-binding transporter confers Ni2 tolerance and Pb2 hypersensitivity in transgenic plants. <i>The Plant Journal</i>, 171-182.</li> | |

| + | </ol> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

Latest revision as of 03:50, 18 October 2014

Wet Lab

Idea

We sought to create genetically engineered strains of E.coli that could sequester the nickel, mercury, and lead from water sources. Each strain included a metal transport protein specific to the respective metal as well as a metallothionein to bind metal ions intracellularly. We first generated basic, functional BioBricks containing: a glutathione-s-transferase gene and yeast metallothionein (crs5) gene fusion for metal binding (BBa_K1460001);[1] the nickel transport gene nixA for selective nickel uptake (BBa_K1460003);[2] the mercury transporter genes merT and merP for selective mercury uptake (BBa_K1460004);[3] and a putative lead transport gene cbp4 for selective lead uptake (BBa_K1460005).[4]To test for sequestration ability of the combined systems, each transport protein in the ampr vector pUC57 was co-transformed with the metallothionein fusion in the cmr plasmid pSB1C3 and selected for using both markers. These strains are functional equivalents of the BioBricks BBa_K1460006, BBa_K1460007, and BBa_K1460008 and were tested for sequestration ability of nickel, mercury, and lead respectively. In addition, the sequestering strains can placed into fiber reactors to develop functional sequestering filters (see dry lab).The idea of utilizing metallothioneins in parallel with metal transporters for sequestration has been studied for mercury and nickel but has never been explored for lead.

Components

Experiments

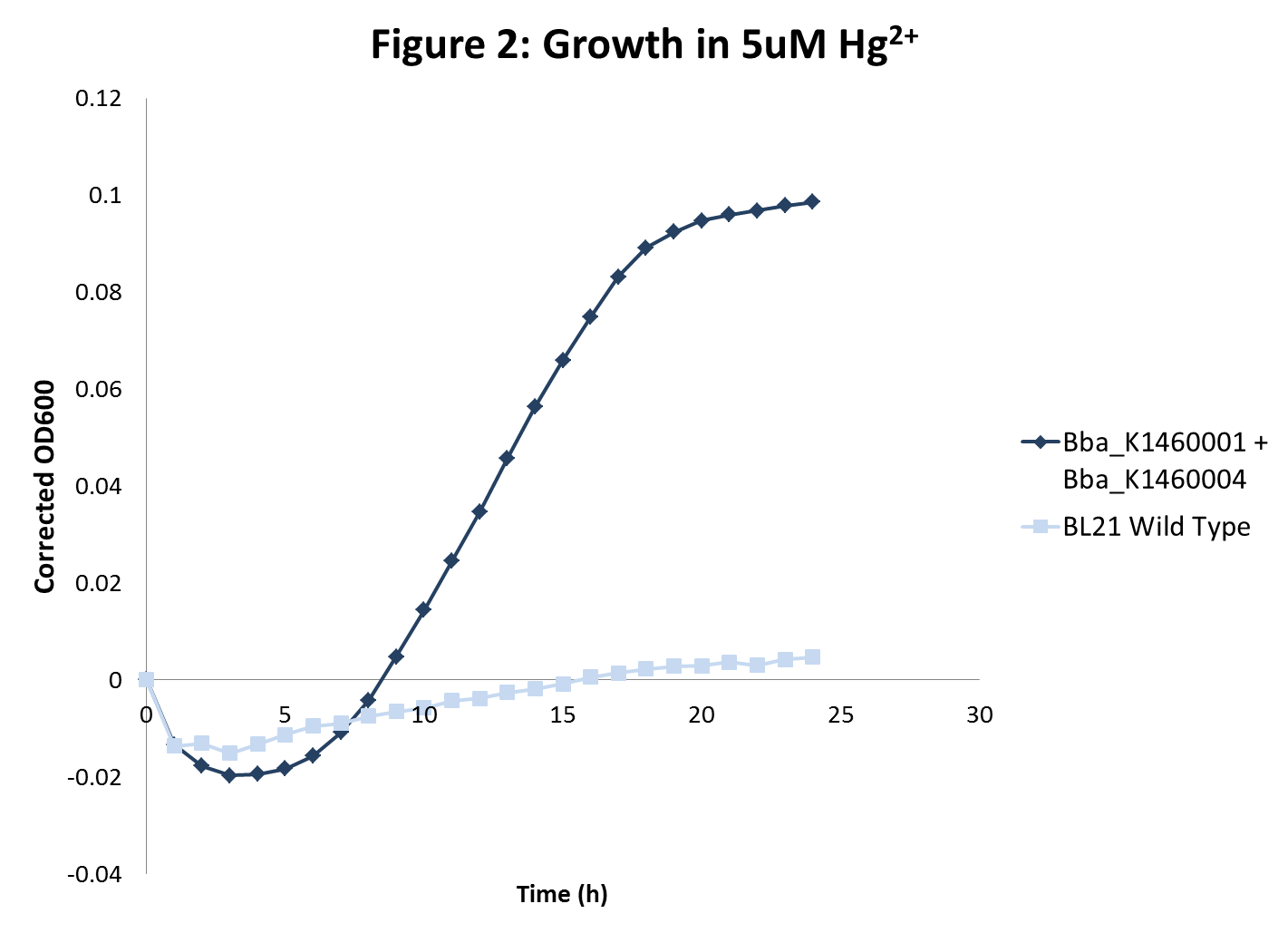

The growth rates of the sequestering strain were measured using spectrophotometry. In addition, two methods were used to determine heavy metal sequestration efficiency.- Spectrophotometer was used to analyze and compare the kinetic growth rates of E. coli cultures expressing only the metallothionein protein, only the transporter proteins, both metallothionein and transporter proteins, and just the vector backbone as a control.

- We hypothesized that the control culture would be mildly sensitive to growth in metal-containing media, while the cultures with the transport protein would be more sensitive to growth in metal-containing media due to increased access of the heavy metal to cellular machinery. Finally, bacteria transformed with both the metal transporter and metallothionein protein would be the least sensitive in metal-containing media. Each strain was grown in different heavy metal concentrations.

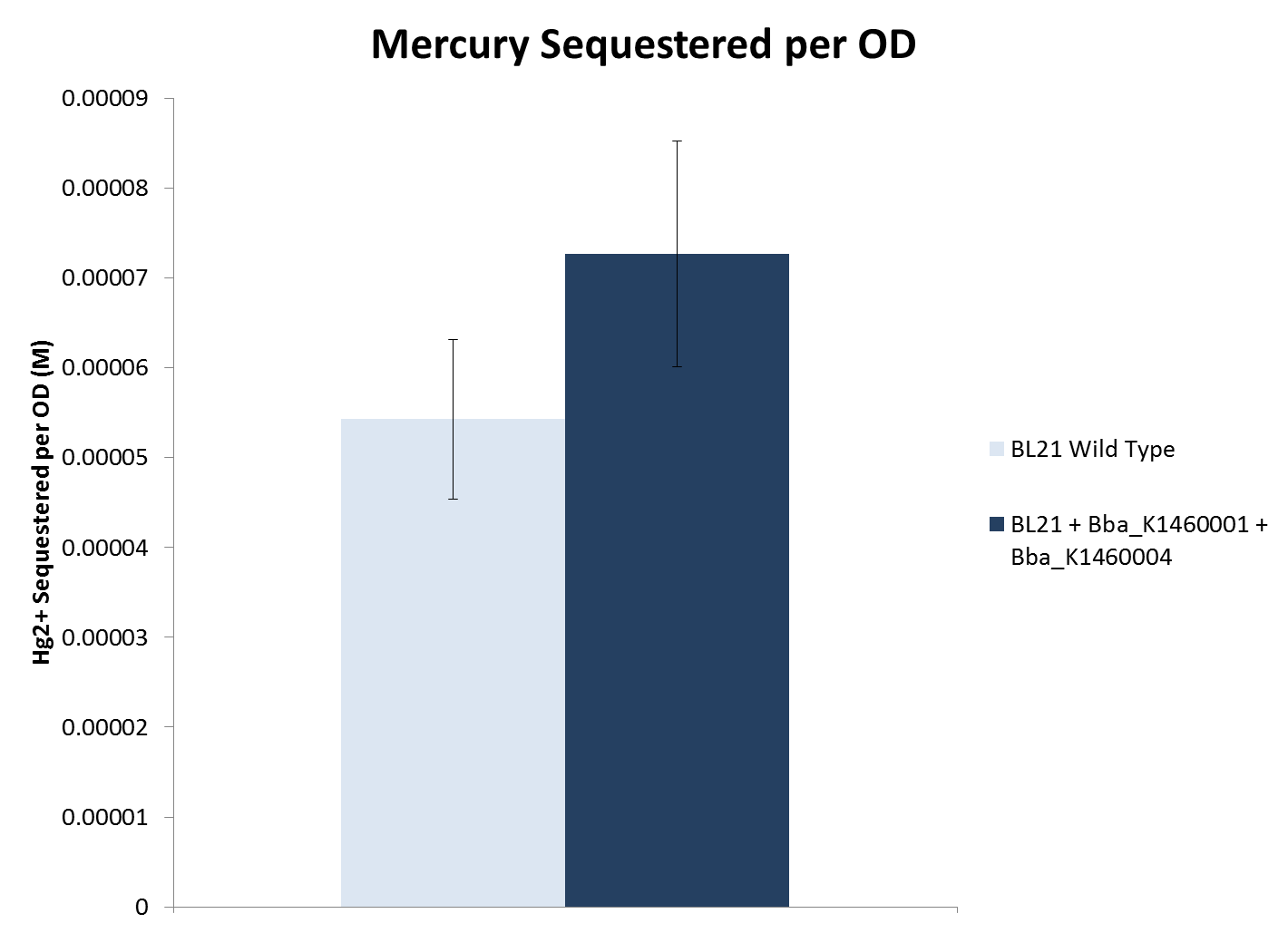

- Sequestration efficiency was measured by growing both the wild type strains as well as sequestering strains in different concentrations of heavy metals. The concentration of heavy metals after growth was measured in two ways:

- Nutrient Analysis Lab at Cornell University using ICP-AES

- Using green-fluorescent heavy metal indicator Phen Green

Results

- BL21 strains with the merT/merP transporters showed increased sensitivity to mercury concentrations as expected. In addition, in high mercury concentrations, wild type strain growth was inhibited more than sequestration strain growths were inhibited. However, there was no inhibition of growth with wild type BL21 or strains with transporters for lead and nickel even at very high metal concentrations.

- When considering cell density, both lead and nickel sequestering strains removed significantly more metal compared to the wild type BL21 strain. The mercury sequestering strain did not remove significantly more metal compared to the wild type strain.

References

- Huang, J. et al. Fission yeast HMT1 lowers seed cadmium through phytochelatin-dependent vacuolar sequestration in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 158, 1779–88 (2012).

- Krishnaswamy, R. & Wilson, D. B. Construction and characterization of an Escherichia coli strain genetically engineered for Ni(II) bioaccumulation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66, 5383–6 (2000).

- Wilson, D. B. Construction and characterization of Escherichia coli genetically engineered for Construction and Characterization of Escherichia coli Genetically Engineered for Bioremediation of Hg 2+ -Contaminated Environments. 2–6 (1997).

- Arazi, T., Sunkar, R., Kaplan, B., & Fromm, H. (1999). A tobacco plasma membrane calmodulin-binding transporter confers Ni2 tolerance and Pb2 hypersensitivity in transgenic plants. The Plant Journal, 171-182.

"

"