Team:Imperial/Mechanical Testing

From 2014.igem.org

Mechanical Testing

Overview

To check the feasibility of using our bacterial cellulose as a customisable ultrafiltration membrane, the mechanical properties were tested. For this to work, we checked the tensile strength of our filter, calculated the shear stress and estimated the processing method that produces membrane with the longest life-time. Our ultimate tensile stress calculated matched with literature values of bacterial cellulose within standard deviation, and the data analysis provided the insight to use non-blended cellulose rather than blended..

Key Achievements

- Introduced a new aspect to the manufacturing track in terms of quantitatively characterising the mechanical properties of our product, bacterial cellulose

- Quantified the tensile stress-strain properties of our bacterial cellulose.

- Discovered that our bacterial cellulose can sustain an order of magnitude higher water pressures than those typically used for ultrafiltration membranes.

- Established that non-blended compared to blended bacterial cellulose was significantly more ductile, and would have longer life time as a water filter, which informed the choice of cellulose for the final product.

- Tested and analysed 20 samples of bacterial cellulose test pieces.

- Created a size and quality optimised gif for visualisation of the experiment and written a protocol for future iGEM teams to do the same.

Introduction

“How long would the bacterial cellulose water filter last? What will be the pressure we can apply on to it?” - Dr. Chipps (Principal Research Scientist at Thames Water)

The most accessible method of finding an answer to Dr. Chipps’ questions is to asses the quality of our material by pulling a test piece until it breaks, a tensile test. The quality of our bacterial cellulose will determine the water pressure that can be applied to it in when used as a customisable ultrafiltration membrane. Since the water pressure is a major limiting factor of the flow rates produced in such a setting, a key step to establishing the feasibility of our project is to perform a tensile test.

Tensile testing of bacterial cellulose is a common way of characterising and comparing its mechanical properties (Khesk 2006, Cheng 2009, Shezad 2010) and provides an indication of the orientation of the fibres in the bacterial cellulose pellicle. Another advantage is that for a polycrystalline material like bacterial cellulose grown in static media, the shear stress, directly related to hydrostatic water pressure, can be interpolated based on Von Mises Criterion.

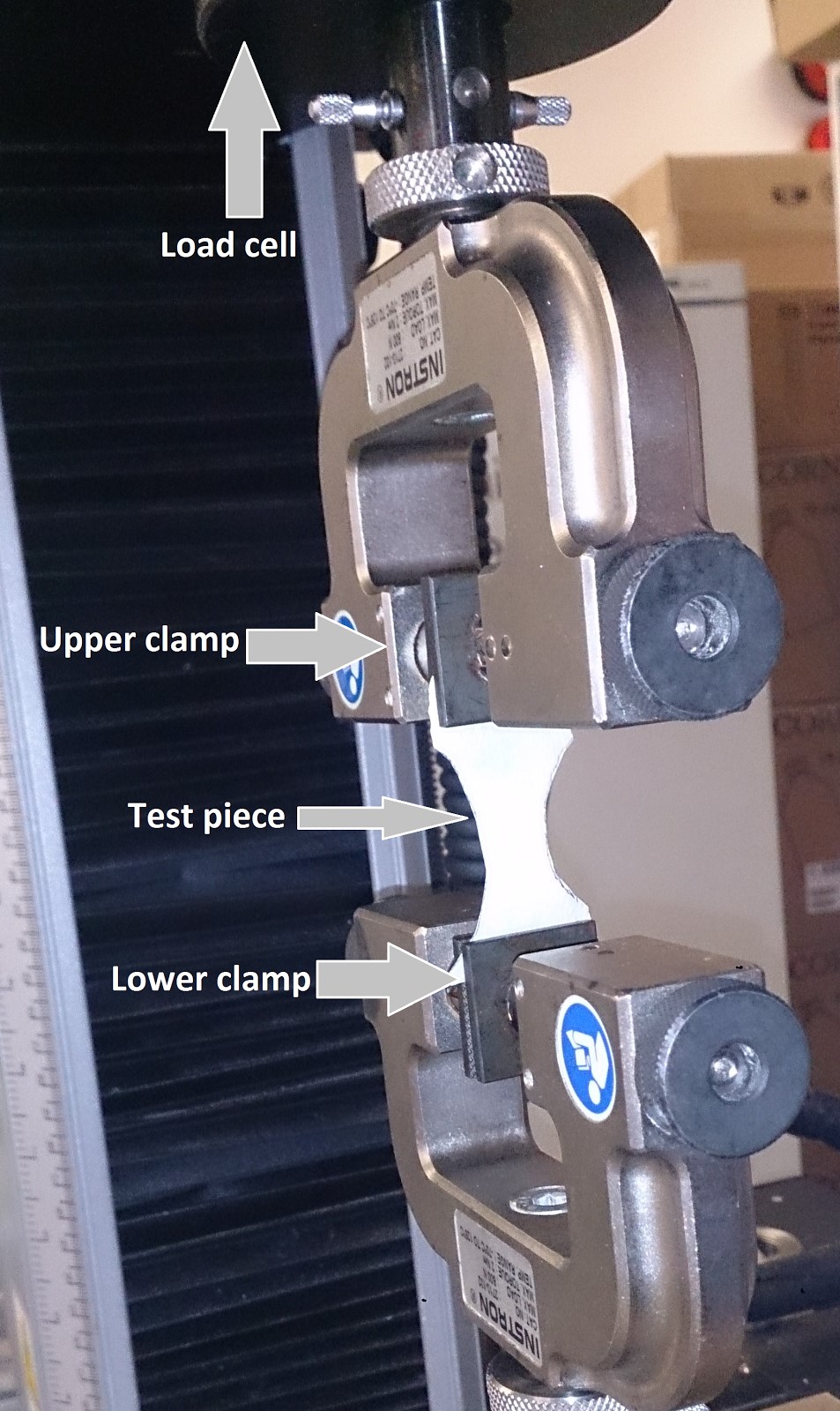

Therefore, we contacted Dr. Angelo Karunaratne of the Royal British Legion Centre of Blast Injury Studies at Imperial College, requesting access to test samples in an Instron 5866 materials testing machine (Instron Inc., Norwood, USA). For this test our aim was to calculate the young’s modulus, ultimate tensile stress, yield stress and strain at failure.

Methods

Samples were prepared by oven drying at 60 C for 6 hours between VWR 413 filter paper, without pressure. Subsequently, samples were kept at room temperature (20 C) before testing. Cellulose was cut into 0.1 mm x 11 mm x 32 mm dumbbell shapes as shown in figure 2 a, following the shape recommended by ISO 527-3 guidelines for determination of tensile properties of plastics. Dumbbell shapes have the advantage of avoiding stress concentration at the clamps, and the dimensions chosen had sufficiently similar small width to large width ratio to literature dimensions (0.16mm × 100mm × 150mm) to allow for comparison across studies (Sherif 2006). A digital vernier calliper was used to measure the thickness of each of the samples. 9 samples were used for the main cellulose fabric intended for water filtration, 2 were used for blended cellulose samples due to limited availability.

The test involves clamping test pieces into the instron machine, moving the upper clamp upwards at a specific elongation time, set to 20 mm/min to match that of existing literature (Sherif, 2006) and tracking the tensile force of the BC sample until the sample fails. Stress() was calculated as the tensile force divided by the cross sectional area measured as width x thickness. Young’s modulus (E) was calculated as stress/strain in the linear section of the average graph. Strain () was calculated as L/L0where L is the elongation from the initial length L0. Samples were tested until visually confirming failure as shown in figure 3.

Two main sample types were tested. The BC pellicles intended for water filtration were immersed in a solution of Wizz Active Oxygen Fabric Stain Remover dissolved in distilled water. After 4 days, the pellicles were removed from the container, cut into squares of 5cm by 5cm, and allowed to dry between VWR 413 filter paper in an oven at 60 ⁰C for 3 hours. Then, the BC layered in filter paper was moved to room temperature, folded in Blue Roll, clamped between heatproof mats with mechanical clamps and left for 24 hours. This type of cellulose will be referred to as non-blended BC.

Alternative BC samples were treated in a 0.1 M NaOH solution in 80C for 3 hours, upon which it was dried off with blue roll and immersed in distilled water. After being in the distilled water solution for 12 hours, the BC was dried of with blue roll and blended in a Jamie Oliver food processor for 12 min at speed 2.

Results

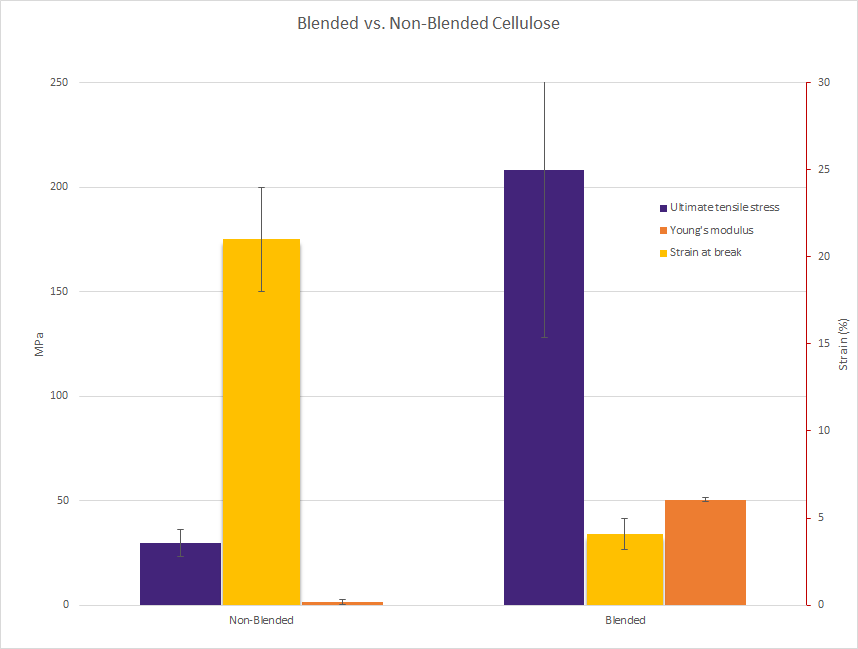

| Sample processing | Ultimate tensile stress (MPa) | Yield stress (Mpa) | Young's modulus (Mpa) | Strain at break (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-blended bacterial cellulose | 29.9 ± 6.4 | 25.2 ± 7.2 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 21 ± 3 |

| Blended bacterial cellulose | 208 ± 80 | 155 ± 11 | 50.5 ± 1 | 4.1 ± 0.9 |

The results of the mechanical tests of blended BC and non-blended BC are shown in table 1. The corresponding measurement data are shown in figure 3 and 4. As shown in table 1, the E, and of non-blended BC was 1.52 MPa, 30 MPa and 35%, respectively. 9 samples were tested to account for variability in cellulose samples produced as graphed in figure 5. The tensile stress is equal within standard deviation to that of 34 MPa found by (Chen 2009), indicating literature levels of tensile strength of the material produced.

As shown in table 1, the yield stress of blended cellulose is 178 MPa higher than that of non-blended cellulose whilst the strain at break was 4% for blended compared to 21% for non-blended cellulose. This indicates that blended cellulose is more brittle than non-blended, making non-blended cellulose a more promising candidate for water filtration. This is because brittle materials are more prone to fatigue-crack propagation (Ritchie 1998) when exposed to cyclic loading characteristic to the use of ultrafiltration membranes, giving brittle materials a shorter expected life time.

Discussion

What is the maximum water pressure that can be applied?

For the cellulose tested with an ultimate tensile stress of 30 MPa and a yield stress of 27 MPa, it is possible to estimate the maximum pressure that our bacterial cellulose filter can sustain by calculating the maximum shear stress (τ). Based on the work of (Jajuee 2006) on membrane filtration, it can be assume that shear stress is the most considerable force acting on the customised cellulose membrane. Combining this with the assumption that non-blended bacterial cellulose is ductile due to being polycrystalline (Tischer 2010), as can be seen in the gif of figure 3 and by the large plastic region shown in figure 7, the Von Mises Criterion can be used to calculate the shear stress. This relates shear stress to yield stress by: σ=√3 τ.Hence, the maximum shear stress is 15.5 MPa. Now, a safety factor of 2 would ensure safe usage of the cellulose membrane, thus a shear stress of half the theoretical maximum shear stress i.e. 7.5 MPa is the advisable working shear stress. This correlates to a hydrostatic pressure of 75 bar, which more than suffices for the pressure ranges of 0.3-3 bar used in ultrafiltration membranes (Reclamation Fact Sheet)

Limitations

In addition to tensile testing, it would be ideal to perform a fatigue stress test as a material like a water filter loaded over many cycles is more likely to fail due to fatigue than tensile loading, which expectedly occur at lower rates than the ultimate tensile stress predicted. To accommodate for this limitation, the cellulose we have produced is being tested by Professor Alexander Bismarck’s group at University of Vienna, which will also provide measurements of its permeability i.e. flow rates at different water pressures. These results are on their way as we speak.

Relevance to Manufacturing track

To the best of our knowledge, characterising the mechanical properties of the various products produced in the iGEM Manufacturing Track has been rather overlooked by previous teams, despite these being key determinants of the feasibility of a product such as biomaterials, glue or polymers for real life implementation. Based on previous year’s lack of tensile test or other more advanced material property tests, we hypothesise that this may be due to limited time and lack of templates for data processing. To accommodate for this lack, we have included a template for analysis of tensile stress-strain data in the appendix, which should reduce the time spent on such endeavours and encourage others to explore the quality of their product.

Appendix

Raw and processed data included for future iGEM teams to use as template for data processing: IC14-Mechanical_Properties_Tensile.xls

References

- Anon, ISO 527-3 official guidelines. Available at: http://211.67.52.20:8088/xitong/BZ\9524171.pdf [Accessed October 12, 2014].

- Anon, Von Mises Stress. Available at: http://www.continuummechanics.org/cm/vonmisesstress.html [Accessed October 12, 2014].

- Cheng, K.-C., Catchmark, J.M. & Demirci, A., 2009. Effect of different additives on bacterial cellulose production by Acetobacter xylinum and analysis of material property. Cellulose, 16(6), pp.1033–1045. Available at: http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?eid=2-s2.0-72849151190&partnerID=tZOtx3y1 [Accessed September 12, 2014].

- Con-Serv Water, Operation and Maintenance Manual. Available at: [http://www.con-servwater.com/uploads/CON-SERV_6_GPM_UF_SYSTEM_OPERATING_MANUAL_7-28-11_Rev.pdf] [Accessed October 12, 2014].

- Jajuee, B. et al., 2006. Measurements and CFD simulations of gas holdup and liquid velocity in novel airlift membrane contactor. AIChE Journal, 52(12), pp.4079–4089. Available at: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/aic.11010 [Accessed October 16, 2014].

- Keshk, S., 2006. Physical properties of bacterial cellulose sheets produced in presence of lignosulfonate. Enzyme and Microbial Technology, 40(1), pp.9–12. Available at: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0141022906004078 [Accessed October 13, 2014].

- Shezad, O. et al., 2010. Physicochemical and mechanical characterization of bacterial cellulose produced with an excellent productivity in static conditions using a simple fed-batch cultivation strategy. Carbohydrate Polymers, 82(1), pp.173–180. Available at: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0144861710003334 [Accessed October 12, 2014].

- Tischer, P.C.S.F. et al., 2010. Nanostructural reorganization of bacterial cellulose by ultrasonic treatment. Biomacromolecules, 11(5), pp.1217–24. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/bm901383a [Accessed October 17, 2014].

"

"