Team:BGU Israel/Project/Intelligent Medication

From 2014.igem.org

Background

The Problem: Insulin resistance in the liver increases the risk for type 2 Diabetes.

The Goal: Increasing the sensitivity to insulin only in liver cells, while avoiding side effects.

Mechanism

Developing tissue specific RNA interference to shut down the esxpresion of PTPN1, a major cause for insulin resistance, only in cells expression APOC3.

Results

-Designed an mRuby2/eGFP scRNA construct for proof of concept.

-Developed a software to automatically design new scRNA constructs, and designed scRNA construct for APOC3 and PTPN1.

Background

As part of our body’s metabolism, insulin is secreted from the pancreas and is in charge of absorbing glucose from the blood into our liver cells. Insulin receptors bind insulin, thus activating a downstream cellular process, which leads to the opening of glucose transporters. Resistance of the liver cells to insulin could lead to hyperglycemia, an increase of sugar in the blood, which increases the risk of diabetes type 2, heart diseases and blood disorders. In addition, insulin resistance leads to an increase in insulin in the blood, which could result in expansion of the fatty tissues in our body. According to recent studies, such insulin resistance could be increased due to gain of body weight(Abbasi, Brown Jr, Lamendola, McLaughlin, & Reaven, 2002).

Presently, a common treatment for insulin resistance is injecting a high dose of insulin to patients in order to increase glucose absorption. However, since insulin is a growth factor, this treatment often leads to the development of cancer. Therefore, an alternative treatment is highly needed(Bowker, Majumdar, Veugelers, & Johnson, 2006).

It is known that insulin resistance shows a significant decrease in the downstream reaction of insulin signal transduction, due to attenuated or diminished signaling from the receptors. Based on many studies, it was found that protein tyrosine phosphatase N1 (PTPN1) has a major role in insulin signaling by dephosphorylating the insulin receptor and inactivating it. Moreover, it was discovered that insulin receptor activity can be enhanced by the inhibition of PTPN1, making it a novel target for reducing insulin resistance(Johnson, Ermolieff, & Jirousek, 2002).

With today’s advanced tools and technology, scientists are able to shut down, or silence, the expression of specific genes in a systemic manner using RNA interference (RNAi). However, while the expression of a protein could have a negative effect in one tissue, it might be essential for another tissue to function correctly. Shutting down the expression of a protein systemically could lead to dangerous side effects.

This is the case with PTPN1. While liver and skeletal muscles are most sensitive to insulin, other tissues have different degrees of sensitivity. Since insulin is essentially a growth factor, as mentioned above, increasing the sensitivity to insulin in tissues other than liver and skeletal muscles could potentially lead to cancer and other side effects.

A common strategy employed to overcome this challenge is targeted delivery, which would ensure the arrival of siRNA only to a desired tissue. We chose a different approach, in which a “smart” siRNA molecule is given systemically, but this molecule can sense its location and activate silencing only in a specific pre-determined tissue. Specifically, we aimed to design a construct which would identify its location inside liver cells, and respond by shutting down the expression of PTPN1.

Mechanism

Our design is based on the idea presented in “Conditional Dicer Substrate Formation via Shape and Sequence Transduction with Small Conditional RNAs”(Hochrein, Schwarzkopf, Shahgholi, Yin, & Pierce, 2013).

To implement this idea, we engineered a small conditional RNA (scRNA) that upon binding to ‘mRNA detection target’ or ‘trigger’, undergoes a secondary structure change to form a Dicer substrate. The Dicer product is siRNA that targets the ‘target mRNA’ for destruction.

Starting with a duplex scRNA, A-B, the detection target X mediates displacement of A (red strand) from B (green strand) to yield a hairpin B with a 2-nt 3′-overhang, which is a Dicer substrate.

After we found our mechanism, it was time to look for the detection target. which would activate the shutdown expression of PTPN1 in liver cells. The main requirement of this detection target is that it would be only expressed in hepatocytes. So, we turned to mRNA expression profiles data-base, RNA Seq Atlas, and found that the gene APOC3 is present in the liver in a significantly higher levels than in other tissues:

Expression of APOC3 in various tissues. Taken from RNA Seq Atlas

To summarize – our scRNA will be given systemically, but will shut down the expression of PTPN1 only in cells expressing APOC3. This way, only hepatocytes are expected to regain sensitivity to insulin, thus limiting side effects.

Click on the picture to check out the machanism

PTPN1 mRNA (blue strand) is present in the cell.

You can read more about the design of the scRNA construct in the results section and about the software we developed to facilitate the design of future constructs.

Results

Expression shut down of eGFP in the presence of mRuby2 mRNA

Since the mechanism of scRNA, developed by Hochrein et al, 2013 was tested only in vitro, we first wanted to design an scRNA construct that will allow us to implement their design in vivo, for the first time.

Choosing the trigger and targetTo our knowledge in the beginning of our project, the two best ways to evaluate RNAi is by reverse transcriptase quantitative PCR (RT qPCR) and flow cytometry. Since our final intention was to silence a non-fluorescent protein, we decided to first try a construct where both the trigger and the target proteins are fluorescent. We already acquired a stable cell line (CT26, mouse colon carcinoma) expressing eGFP, we chose eGFP as our silencing target. To test our construct for specificity, we needed to be able to control the expression of the trigger mRNA, so we decided that our trigger mRNA will not be an endogenous mRNA of CT26. We agreed to use mRuby2, another fluorescent protein, and ordered pcDNA3 mRuby2 from Addgene.

Design and synthesis

The functionality of the construct is directly controlled by RNA interactions and secondary structures. Therefore, we used an online secondary structure prediction tool, Nupack.

Design steps

Secondary structure prediction of detection target mRNA (of mRuby2):

- Identification of low probability unpaired bases regions, which will be more readily available for strand displacement.

- Select a 29-nt long subsequence which will directly interact with part A of the construct (a+b+c sequences, see mechanism figure above).

- Sequences y and z which form the final siRNA were decided to be a known sequence of anti eGFP siRNA: 5’-CAGCCACAACGUCUAUAUCAU-3’.

- With sequences a,b,c,z and y we built all the sequences, according to the mechanism figure (letters denoted with * represent reverse complements).

The final sequences are:

It is important to note the part A consists of 2’-OMe modified nucleotides that increases the construct’s stability.

Design results:

A successful construct has 3 requirements:

- Interaction between A and B

- A should have a preferred interaction with the detection target over B

- When not interacting with A, B should have a secondary structure of a short hairpin.

Our design answers all 3 requirements has can be seen by the Nupack simulations we performed:

Interaction between A and B:

Interaction between A, B and mRuby2 mRNA (shortened to avoid cluttering):

The products of this reaction are equimolar amounts of mRuby2:A (in the picture) and B as a hairpin, as desired.

Part B alone has a second structure of a short hairpin:

Experiments

Validation of co-expression of mRuby2 and eGFP in CT26 eGFP cell line

Before beginning the actual silencing experiments, we wanted to be sure both mRuby2 and eGFP can both be expressed in CT26 eGFP cell line. This was visualized using confocal microscopy:

All three pictures show the same cells. Picture A shows only eGFP expressing cells, picture B shows only mRuby2 expressing cells, and picture C show all cells.

Functional silencing experiments

We began our functional experiments by using only flow cytometry. We didn’t see a significant decrease in the expression of eGFP even in our positive control, and concluded that flow cytometry is not a good analysis tool in our case. So we decided to continue using RT qPCR.

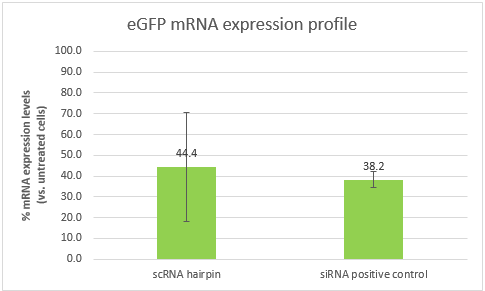

As explained above, part B alone is a Dicer substrate and leads to silencing. So first we wanted to see if our part B can indeed silence eGFP in CT26 eGFP. We transfected CT26 eGFP cells with part B and a positive control siRNA (elaborated in the notebook, week 10).

These results are an indication that part B can silence eGFP, and in a similar efficiency to that of our positive control. However, the high standard deviation, will require us to repeat the experiment. It is also important to note that the efficiency of both samples is affected by the transfection efficiency, which is dependent of the transfection reagent. Optimizing the transfection might lead to better results and higher silencing efficiencies.

Expression shut down of PTPN1 in the presence of APOC3 mRNA

Using our scRNA design software, we produced sequences of parts A and B for the PTPN1/APOC3 construct.

We also designed and ordered TaqMan primers for PTPN1 and APOC3.

References

Abbasi, F., Brown Jr, B. W., Lamendola, C., McLaughlin, T., & Reaven, G. M. (2002). Relationship between obesity, insulin resistance, and coronary heart disease risk. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 40(5), 937–943.

Bowker, S., Majumdar, S., Veugelers, P., & Johnson, J. (2006). Increased Cancer-Related Mortality for Patients with Type 2 Diabetes who use Sulfonylureas or Insulin. Diabetes Care, 29(2), 254–258.

Hochrein, L. M., Schwarzkopf, M., Shahgholi, M., Yin, P., & Pierce, N. a. (2013). Conditional Dicer substrate formation via shape and sequence transduction with small conditional RNAs. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 135(46), 17322–30.

Johnson, T. O., Ermolieff, J., & Jirousek, M. R. (2002). Protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B inhibitors for diabetes. Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery, 1(9), 696–709.

http://medicalgenomics.org/details_view_limited?db=rna_seq_atlas&gene_id=345

"

"