Team:Marburg:Project:Silver

From 2014.igem.org

Silver Surfer

"Surfing is a surface water sport in which the wave rider, referred to as a surfer, rides on the forward or deep face of a moving wave, which is usually carrying the surfer towards the shore."

In modern science, at the limits of visualization and detection feasibility, the

amplification of signals is a serious challenge. Scaffolding – building a high

density of factors in close proximity – is the key to optimize chemical reactions or

increasing signals for detection. Here we use the bacterial flagellum, a structure provided by nature itself,

as a toolbox for different applications. This huge formation consists

of the basal body, the hook and the filament, which is composed of up to 20.000 copies of the protein Flagellin (Figure 1). Due to the rotating flagellum bacteria are able to

surf through their environment.

Figure 1: Composition of the bacterial Flagellin filament.

Figure 1: Composition of the bacterial Flagellin filament.

Among bacteria, Flagellin is a protein with highly conserved domains such as D0 and D1, whereas the sections D2 and D3 are extremely variable (Figure 2) (Yonekura et al. 2003). By comparison of Salmonella, Sphingomonas and Bacillus Flagellin it is remarkably that Bacillus D2 and D3 is reduced to a small loop (Figure 2) (Altegoer et al. 2014).

Figure 2: Conserved protein domains of Flagellin among different bacteria.

Figure 2: Conserved protein domains of Flagellin among different bacteria.

This fact was the reason we took a closer look at the Flagellin of Bacillus subtilis. Our vision is using the bacterial flagellum as a scaffold for high density accumulation of proteins with valuable functions.

“SURFing (Synthetic Units for Redirecting Functionalities) is the redirection of natural occurring structures to a high density surface which can be modified for different purposes, towards solving important challenges for humanity e.g. reduction of environmental pollution and improvement or development of new medical applications. (Figure 3)” (iGEM Marburg 2014).

Figure 3: SURFing application workflow.

Figure 3: SURFing application workflow.

Utilizing the principle of SURF on the basis of bacterial flagella, we decided to contribute to the reduction of environmental pollution, concerning heavy metal ions, some of which expose a high toxicity and are harmful even in small doses. A well known representative of these kind of metals is silver (Ag). The toxic effect is on the one hand industrially welcome, as silver is used as an additive to kill bacteria on the other hand it is a big problem due to its dissemination by industrial waste water. Thus the SilverSURF project was born.

SilverSURF

The purpose of the SilverSURF project is to catch ions from soil or solutions and bind them with a high affinity. How should this be realized? Our vision is to introduce an additional modified copy of Flagellin into the genome of Bacillus subtilis. This allele should be controlled by a silver ion sensitive promoter. In presence of silver ions the modified Flagellin is expressed and incorporated into the filament. This modified Flagellin is a chimeric protein with a new domain – the metal binding part of the metallothionein Cup1 from yeast which specifically binds silver and copper ions (Moore et al. 2005). This leads to engineered B. subtilis cells, which catch the surrounding ions from their environment(Figure 4).

Figure 4: SilverSURF vision.

Figure 4: SilverSURF vision.

There are many published data about transcriptional changes due to heavy metal ion stress in B. subtilis; we were able to find specific promoters, which are more or less specific for certain metals. We established a reporter system to analyze different promoters and used the promoter of argJ or the arg-operon respectively for sensing silver ions and the promoter of ykuO or its operon for the detection of copper ions, by generating a highly modular amyE locus integration plasmid with a GFP reporter. By analyzing our reporter constructs via STED microscopy, we saw that the chosen silver sensitive promoter does not show any differences by exposure to different silver concentrations compared to our negative control without silver ions (Figure 5). In principle the established promoter reporter system works though.

Figure 5: SilverSURF promoter reporter system with silver concentrations 0, 0.1 µM and 10 µM.

Figure 5: SilverSURF promoter reporter system with silver concentrations 0, 0.1 µM and 10 µM.

Nevertheless we focused onto the Flagellin Cup1 chimera (Moore et al. 2005). We designed a modular system for chromosomal integration, where the hag gene, which codes for Flagellin, features a SpeI site for fast and modular insertion of domains via Gibson Assembly (pIGEM-0016). The Cup1 module was amplified from Saccharomyces cerevisiae genomic DNA integrated into the pIGEM-0016 system and the wild type hag was successfully replaced with the chimeric hag-cup construct. pMAD allows high efficiency allelic replacement of the wild type hag via the pMAD system (Arnaud et al. 2004).

Motility Assays and structural analysis

As an in vivo functional test of the engineered Flagellin, swimming and swarming assays were performed. Unfortunately the assays showed that the engineered Flagellin containing strains were strongly reduced in their motility compared to both the wild type strain WT3610 and the control strain producing our modularized Flagellin Hag-SpeI without the inserted Cup1 domain.

Anyway, to learn what might disrupt the flagellum functionality, the Hag-Cup1 was overexpressed in Escherichia coli. Sufficient amounts of protein could be purified, which were subjected to crystallization to solve the structure of the chimeric protein. Crystals could be obtained but the structure could only be solved partially, due to the disruption of the D1 domain by the Cup1 integration into Hag.

This results led us to rethink our approach and we concluded that the Flagellin might be functional if we replace the Bacillus loop with the D2 Domain of Salmonella typhimurium (Figure 2) and use it as a linker for the Cup1 (Figure 6). This construct is further on called Hag-D2-Cup1.

Figure 6: New engineered synthetic D2-Cup1 Flagellin.

Figure 6: New engineered synthetic D2-Cup1 Flagellin.

At the same time we developed the idea to insert a StrepTag into the Hag-D2 construct which would provide an enormous flexibility by coupling a multitude of functional proteins to streptavidin and further on build extracellular complexes of Flagellin with chimeric streptavidin proteins (for further information see the CancerSURF project).

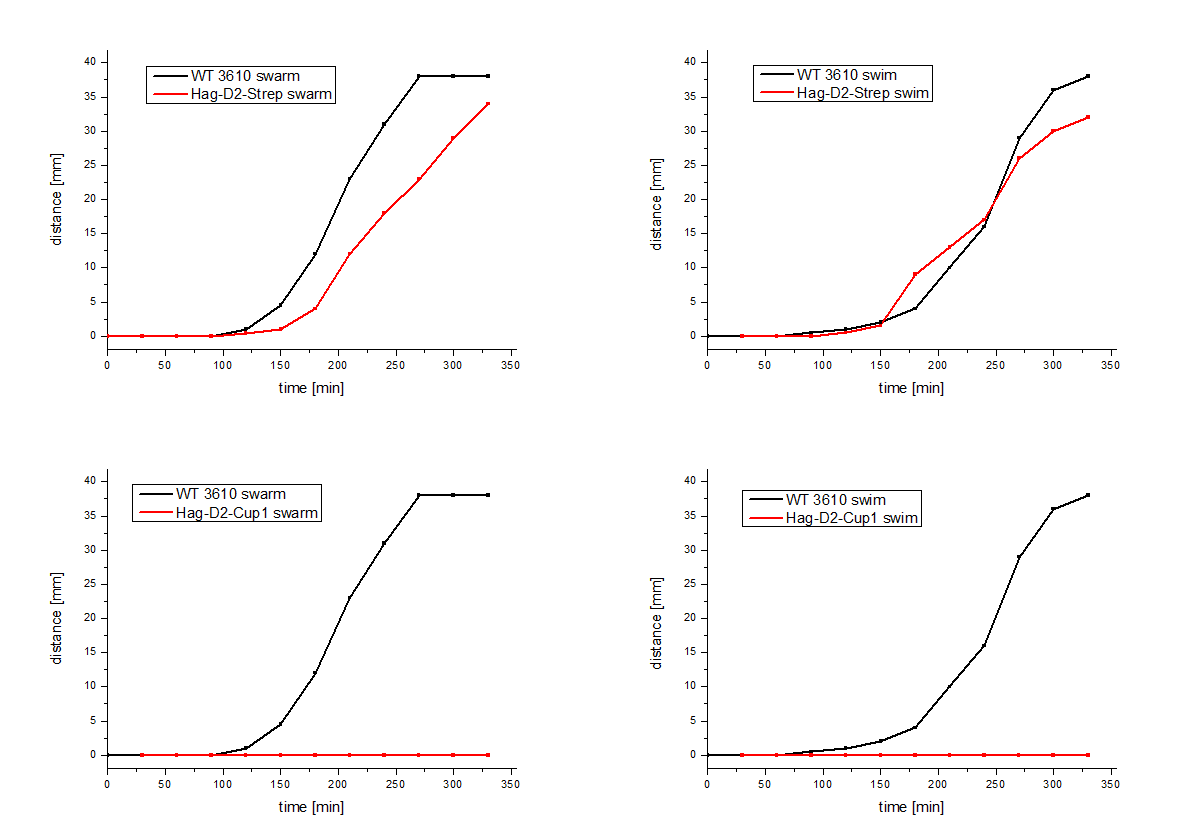

The Hag-D2-Cup1 and Hag-D2-Strep were also integrated into B. subtilis via homologous recombination by using our modular pMAD system. Again motility assays were performed, which showed comparable results for Hag-Cup1 and Hag-D2-Cup1 though the strain containing Hag-D2-Strep behaves similar to the wild type in this assay (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Motility assays of the Hag-D2-Cup1 and the Hag-D2-Strep.

Figure 7: Motility assays of the Hag-D2-Cup1 and the Hag-D2-Strep.

We asked ourselves how can one construct show a wild type like phenotype but the other not. Therefore, we visualized the flagella by using electron microscopy with an uranyl acetate negative staining of our different Bacillus strains (Figure 8). To our surprise we could show that the Hag-D2-Cup1 strain is able to form filaments though they are much shorter and inflexible, compared to the wild type Flagella, which might be the reason why we observed fragmented filaments. Astonishingly the Hag-D2-Strep filaments looked like wild type filaments. Although we observed less filaments they seem to be functional. What might be the difference between Hag-D2-Cup1 and Hag-D2-Strep is part of further investigations. A major factor could be the smaller size of the StrepTag, which consists of only eight amino acids, in contrast to the 4.5-fold bigger part of the Cup1 (36 amino acids).

Figure 8: Uranylacetate negative stained electron microscopy of B. subtilis (A) and engineered strains (B).

Figure 8: Uranylacetate negative stained electron microscopy of B. subtilis (A) and engineered strains (B).

The successful engineering of the Hag-D2-Strep Flagellin is the cornerstone for the success story of our CancerSURF project. In further investigations we plan to couple Cup1-Streptavidin, which was successfully produced recombinantly, to isolated Hag-D2-Strep filaments for our SilverSURF – this would directly optimize our approach for pollution reduction. Beyond that, there is no need to use the GMO outside the laboratory. The isolated recombinant Flagella could be used directly so no major safety concerns would emerge. Also the higher level of modularity allows us to couple every imaginable high value applicable protein to our filaments. There is no reason to use only one protein, we also plan to use different proteins coupled to streptavidin and bring them into close proximity by using the filaments as a scaffold for molecular crowding. There are unlimited high valuable applications for this system to solve all kinds of challenges the humanity is faced with.

Altegoer, Florian; Schuhmacher, Jan; Pausch, Patrick; Bange, Gert (2014): From molecular evolution to biobricks and synthetic modules: a lesson by the bacterial flagellum. In: Biotechnology and Genetic Engineering Reviews 30 (1), S. 49–64. DOI: 10.1080/02648725.2014.921500.

Arnaud, Maryvonne; Chastanet, Arnaud; Débarbouillé, Michel (2004): New vector for efficient allelic replacement in naturally nontransformable, low-GC-content, gram-positive bacteria. In: Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70 (11), S. 6887–6891. DOI: 10.1128/AEM.70.11.6887-6891.2004.

Moore, Charles M.; Gaballa, Ahmed; Hui, Monica; Ye, Rick W.; Helmann, John D. (2005): Genetic and physiological responses of Bacillus subtilis to metal ion stress. In: Molecular Microbiology 57 (1), S. 27–40, zuletzt geprüft am 16.10.2014.

Yonekura, Koji; Maki-Yonekura, Saori; Namba, Keiichi (2003): Complete atomic model of the bacterial flagellar filament by electron cryomicroscopy. In: Nature 424 (6949), S. 643–650. DOI: 10.1038/nature01830.

"

"