Team:Heidelberg/pages/PCR 2.0

From 2014.igem.org

Abstract

DNA methylation is the most abundant DNA modification and essential for embryonic development, gene regulation and genomic stability. Although several methods for the detection of methylation patterns exist, there is no easy way to amplify methylated DNA for in vitro or in vivo studies.

To empower epigenetic research, we envisioned a PCR2.0 which maintains DNA methylation patterns during amplification. The central element of this PCR2.0 is a heat-resistant DNA methyltransferase -DNMT1(731-1602)- which we created by circularization using our intein toolbox and the CRAUT linker software.

So far, our DNMT1 represents the largest circularized protein which highlights the usefulness of our intein toolbox in combination with the CRAUT linker software. Increased heat resistance of our circular DNMT1 which was observed in initial assays smooth the path for the establishment of a PCR2.0 and illustrates the suitability of intein-mediated circularization for the advancement of heat resistant proteins.

Highlights

- Heat-stabilization of mDNMT1(731-1602) as pivotal element of a methylation maintaining PCR2.0.

- Biggest circularized protein so far.

- Successful application of rational linker design with CRAUT linker software.

- Efficient expression and purification of active linear/circular mDNMT1(731.1602) in E.coli.

- Establishment of a methylation activity assay that allows quantification of activity and specificity.

Contents |

Introduction

Motivation

The invention of the polymerase chain reaction in 1983 by Kary Mulliy revolutionized the modern world by enabling amplification of DNA in an exponential manner. Further improvements including the use of thermo-stable DNA-polymerases made the method even more efficient, allowing its widespread use in nearly every field of modern diagnostics and research. However, a major part of information is lost when using conventional PCR due to missing transfer of DNA modifications. The most abundant modification is DNA methylation, which is present in all kingdoms of life where it acts as prominent regulator of gene expression. Methylation and other modifications that influence the DNA function without changing its actual sequence are studied in the fast-growing field of epigenetics (greek: epi/επί-over, above, around).

To empower epigenetics, we propose the PCR 2.0 as an easy and efficient way to amplify DNA templates in an exponential manner while maintaining their specific methylation pattern. The pivotal element of this PCR reaction is the use of a heat-stable DNA methyltransferase (DNMT). Although comparable enzymes exist in thermophile organisms [1] until now no suitable protein has been found or synthesized that withstands the harsh conditions of a PCR.

Even though the detection and mapping of methylation patterns has become feasible in a high-throughput manner by using bisulfite sequencing and array techniques [2], further functional analysis is still hindered by the small amount of primary material. Our approach therefore aims to provide unlimited amounts of any methylated DNA sample of interest, without knowledge of methylation patterns or the need of expensive methods such as de-novo synthesis – just by running a PCR.

To achieve this goal of a PCR2.0 that can be used to amplify DNA including its intrinsic methylation pattern, our main aim was the generation of a heat-stable Dnmt1 that can be produced in a larger scale and shows efficient and specific methylation of DNA. Our approach applies protein circularization by using self-splicing protein sequences, socalled inteins from our toolbox as well as our CRAUT Linker Software. Since the restriction of conformational changes through intramolecular bonds has been known to increase the stability of proteins [3] [4] and joining of C- and N- terminus were reported to increases in thermostability of smaller peptides [5] we started the circularization of the biggest protein so far…

Epigenetics - there is more than just A, T, C and G…

In mammals and other vertebrates methylation occurs at cytosine nucleotides that are followed by guanines (CpG) and is a prominent key regulator of transcription, embryonic development, X chromosome inactivation and many other cellular functions. [6] [7]. Approximately 1% of the genetic code in human somatic cells constists of methylated cytosines, amounting to 70-80% of all present CpG dinucleotides [8]. Due to the great prevalence and the heredity of this modification, the 5-methylcytosine (5mC) is also known as the “fifth base” of eukaryotic genomes [9]. DNA methylation is preferentially occurring at intergenic regions and repetitive sequences, where it is known to silence gene expression [10] [11]. In contrast, GC-rich promoter regions are usually characterized by a low methylation status, allowing transcription of the associated genes [12]. Deregulation of cytosine methylation has been reported to play a crucial role in the development of numerous diseases, including cancer, imprinting diseases and repeat-instability based diseases such Huntington's disease [13].

A closer look at DNA Methyltransferases

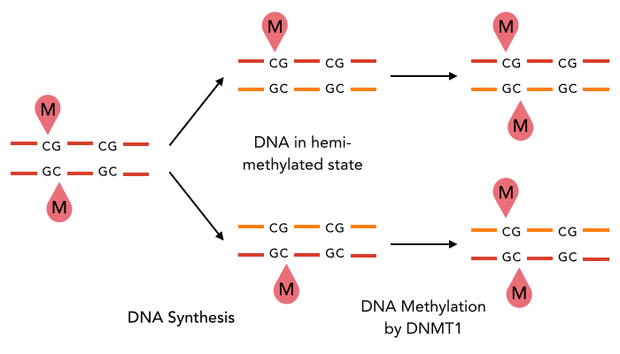

The family of enzymes called DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) is responsible for the establishment and maintenance of cell-type specific DNA methylation patterns. Whereas the two enzymes DNMT3a and DNMT3b contribute to de novo methylation of DNA during development, DNMT1 is preserving existing methylation patterns throughout cell divisions. To do so, DNMT1 exploits the principle of semiconservative replication, using the parental strand as a template to create an exact copy of methylation patterns on the daughter strand. Subsequent to the recognition of a so called hemi-methylated CpG site, the enzymatic machinery transfers a methyl group from the methyl donor S-Adenosyl-methionine (SAM) to the C5 position of the complementary cytosine residue [15] [19].

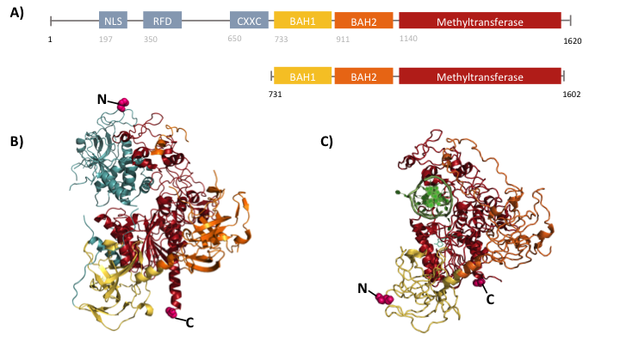

Structural overview of full length mDNMT1 and truncated mDNMT1(731–1602) (A) Color-coded schematic overview of domain structure and numbering of mDNMT1 sequence. (B) Ribbon presentation of full-length DNMT1 with the CXXC,BAH1, BAH2,and methyltransferase domain colored in light blue, yellow, orange and red, respectively. (C) Crystal structure of truncated DNMT1, missing the CXXC domain and schowing more adjacent protein termini thatn the full-length version.

The complex structure of DNMT1 and several truncated versions have been recently solved by X-ray crystallography [19]. For our experiments we used the smallest truncated version of DNMT1 that has been reported to efficiently mediate methylation maintenance. This truncated version derives from Mus musculus and comprises amino acids 731-1602 (mDNMT1(731-1602) [15] [19] kindly provided by Dr. Bashtrykov after approval from Prof. Patel). mDNMT1(731-1602) contains the C-terminal catalytic methyltransferasedomain as well as the aligning bromo-adjacent homology (BAH) domains, which prevent the binding of unmethylated DNA to the catalytic core. The truncated enzyme is missing the CXXC domain, which has a high affinity to CpG hemi-methylated dinucleotides, but was shown to be dispensable for protein function [16]. In contrast to the full-length DNMT1 that can only be expressed in insect cells using a baculovirus based system, mDNMT1(731-1602) has the great advantage of being efficiently expressed in E.coli. Another advantage of the truncated DNMT1 is, that the N- and C- terminus are closer together than in the full-lentgh DNMT1. Thus cirularization might cause less deformation and show lower impact on the overall activity, which makes this truncated mDNMT1 an ideal target for our purposes.

Circularization - The missing link

Heat stabilization of mDNMT1 as a pivotal element of our methylation-maintaining PCR2.0 was approached by circularization of the protein. Until now, only smaller proteins have been stabilized using this method. Therefore, to our knowledge, mDNMT1 – even in its shortest truncated version of 871 amino acids and a molecular weight of approximately 100kDa – is the largest protein that has ever been tried to circularize. According to the crystal structure, the distance between the termini of the truncated DNMT1 is 48 Å. We suspected that circularization of the protein by direct fusion of both termini might cause deformation of the protein structure. Therefore we used our own CRAUT Linker Software to create a linking amino acid sequence, adapted to the structure of DNMT1. The software is able to design protein linkers with the required length to bridge the gap between the protein termini while bypassing the catalytic core of the enzyme.

Since we could not estimate the impact of the linker introduction, we focused on two different kinds of linkers: a so called rigid linker that has been calculated and optimized during the establishment of our linker software and a flexible peptide connection consisting mostly of glycine and serine. To perform circularization we have used the split NpuDnaE Intein since it is used as the golden standard for protein splicing and has been efficiently tested by us through circularization of GFP, Lysosyme and Xylanase. Moreover, we tried to implement protein circularization by using sortase A, which is recognizing and cleaving a carboxyterminal sorting signal followed by a transpeptidation reaction that can be exploited for protein circularization. This method has been reported to be very efficient, especially when used in vitro [4] and was therefore included in our study as possible candidate for large scale productions of circular proteins.

Materials and Methods

Constructs

We designed constructs in order to characterize the efficiency of sortase A as well as intein mediated circularization of DNMT1. Both approaches are based on the comparison of the circularized protein with a corresponding linear counterpart at different temperatures and incubation times.

For circularization of DNMT1 with inteins we fused the obtained truncated version of DNMT1 (731-1602) [15] with an appropriate linker and split NpuDnaE domains at either site of the construct. For efficient purification of the protein, all constructs contained a hexa-histidine tag. Moreover, we have cloned the ubiquitin-like Smt3 protein from Saccharomyces cerevisiae in front of the DNMT1-intein complex. This attachment is used to increase the yield when expressing large mammalian proteins like DNMT1 in E.coli [17]. The constructs have been designed in a way that Smt3 is no longer included in the final circular protein, and therefore cannot interfere with its function. All cloning steps were carried out using our new RFC[i] standard procedure.

The mDNMT1 (731-1602) constructs that have been designed to allow sortase A mediated cirularization are flanked by the sortase A recognition sequence LPETGG on the C–terminus as well as N-terminal glycines that that can be exposed through previous TEV treatment. Since the transpeptidation via sortase requires an additional in vitro reaction, subsequent purification is necessary. To facilitate this step and to enrich the circular product in the sample, a hexa-histidine tag is present in the initial protein that is lost during circularization. Hence, an additional affinity chromatography via His trap can be used to separate the histidine tag containing sortase and not circularized educt from the circular flow-through. All cloning steps were carried out using our sortase standard.

The following linkers that had been optimized along with our CRAUT Linker Software:

| Definition | Sequence |

|---|---|

| Rigid linker | GGAEAAAKEAAAKVNLTAAEAAAKEAAAKEAAAKEAAAKEAAAKAVNLTAAEAAAKAHHHHHHSGRGT |

| Flexible linker | CWEGGGSGGGSGGGSGGGSGGGSGGGSGGGSGGGSGGGSGGGSHHHHHHSGRGT |

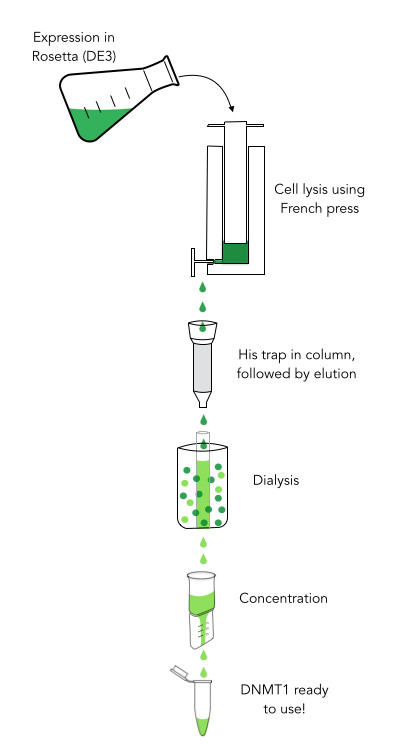

Expression and purification

The purification of recombinantly expressed mDNMT1 is a challenging task including large scale induction, efficient cell lysis, reduction of sample volume via ultracentrifugation, immobilized Ni-ion affinity chromatography, dialysis and concentration through centrifugation.

In comparison to the full length murine DNMT1, our modified mDNMT1(731-1602) can be expressed in E.coli (Rosetta DE3) and does not need the establishment of Baculovirus based system and the use of insect cell cultures. First experiments were conducted to determine the optimal conditions for protein induction and expression. We tested several concentrations of IPTG as well as different temperatures to maximize the yield of mDNMT1. Still, even though expression of the constructs can be simplified by using E.coli, purification of the recombinant protein remains a challenging task requiring multiple different steps that had to be adapted and established from published protocols [19].

In a first step, we optimized the process of cell lysis, to be able to extract a maximum amount of active protein from our cultures. Therefore we compared the two commonly used methods sonication and disruption via French press. Subsequently, the sample was cleared from cell debris by ultracentrifugation. The protein of interest containing a hexa-histidine tag was further enriched via immobilized metal ion affinity chromatography (IMAC) using a His trap and eluted with imidazol. In a next step, low molecular weight solutes such as salts and imidazol that would interfere with protein function were removed from the sample by dialysis. Finally, the purified protein was concentrated by size-exclusion centrifugation using filters with an appropriate mass cutoff.

Methylation activity assay

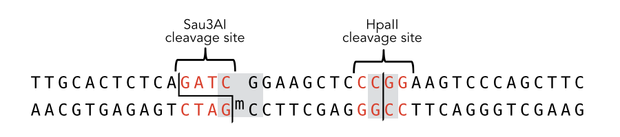

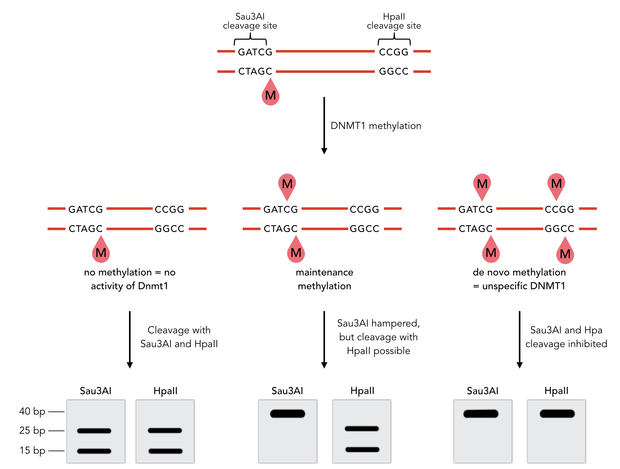

To measure the efficiency of mDNMT1 maintenance methylation, we used an assay that is based on two methylation-sensitive restriction enzymes Sau3AI and HpaII. It relies on the inhibition of restriction enzymes when methyl groups are attached to the cleavage site. We used a 40-mer DNA template with one hemi-methylated and one unmethylated CpG site which are located within the Sau3AI and HpaII restriction site, respectively (adapted from Bashtrykov et colleagues [16].

Principle of mDNMT1 methylation assay using a 40-mer substrate with Sau3AI and HpaII cleavage sites that are blocked upon further CpG methylation. The lack of methylation activity leads to fragmentation of the DNA template with either of the two restriction enzymes. Whereas specific methylation of hemimethylated CpGs hampers only cleavage by Sau3AI, de novo methylation activity of mDNMT1 can be detected when HpaII cleavage is blocked as well.

The restriction enzyme Sau3AI is capable of cleaving the template despite of the hemimethylated state of the first CpG nucleotide. Similarly, HpaII can attack its unmethylated native site, leading to fragmentation of the template as long as no further methylation occurs. Accordingly, the methylation activity of circular and linear mDNMT1 can be measured by quantifying the cleavage efficiency of the restriction enzymes after incubation with the protein. Impairment of Sau3AI cleavage indicates maintenance methylation activity, whereas a decrease in HpaII activity would result from de novo methylation. Therefore the assay is not only detecting activity of the enzyme but also includes its specificity for hemimethylated DNA over unmethylated DNA. To quantify maintenance and de novo methylation activity, the 40-mer fragments remaining after DNMT1 incubation and restriction digest were separated by gel electrophoresis. The intensities of the detected bands corresponding to different fragments were measured using ImageJ Gel Analyzer and quantified using gaussian fitting after background substraction.

Results

Optimizing expression and purification of linear mDNMT1(731-602)

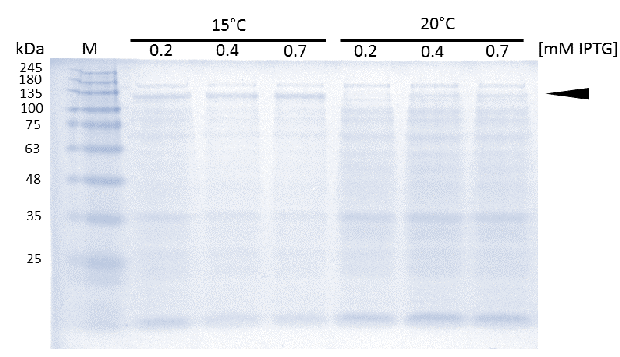

As soon as transformed Rosetta (DE3) cultures reached an OD600 of approximately 0.6, induction of linear mDNMT1(731-1602) was perfomed over night at either 15°C or 25°C, using different concentrations of IPTG. Higest expression of DNMT1 was observed at 15°C using 0.7mM IPTG.

Before starting circularization of DNMT1, we first tested if we can actually express and purify active linear DNMT1. Since DNMT1 expression in E.coli normally results in low yields (<1mg/liter of culture)[15], we started with an optimization of the expression conditions.

In general, low temperatures and low IPTG concentrations are known to prevent the occurrence of insoluble inclusion bodies under conditions of overexpression. Thus, we tested different IPTG concentrations and temperatures during induction in order to maximize yields of active mDNMT1(731-1602). Generally, solubility tags such as the fused Smt3 as well as lower temperatures are known to prevent the occurrence of insoluble inclusion bodies under conditions of overexpression. Accordingly, we observed an optimal induction of our mDNMT1(731-1602) construct after incubation at 15 °C using 0.7mM IPTG (Figure 5).

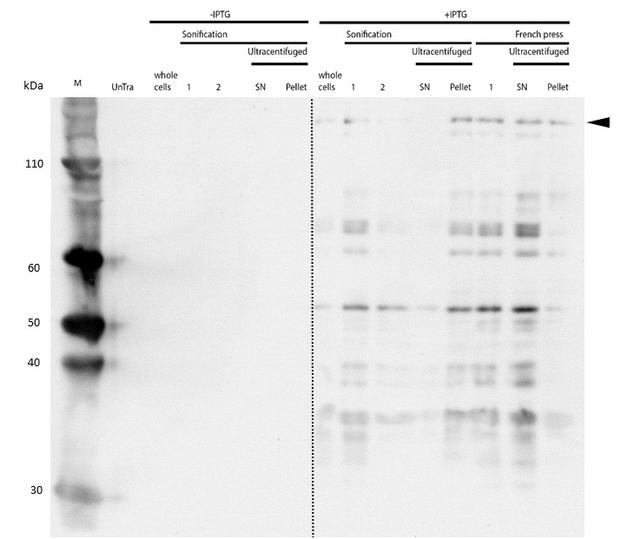

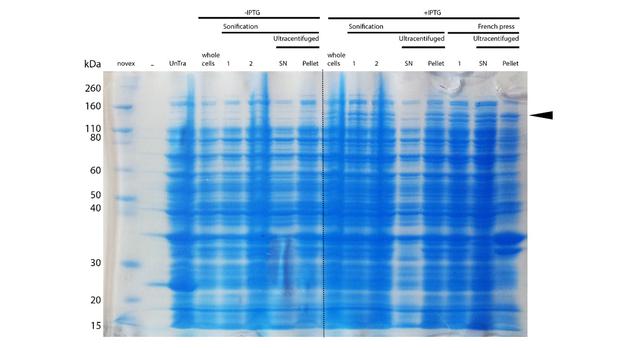

Even though the overall yield of recombinant protein is quite low, the presence of mDNMT1(731-1602) after induction with IPTG was detectable through Coomassie staining and specifically verified by Western blot (Figure 6A and 6B). In the western blot, several other peptides with lower molecular weight were detected (Figure 6B). These peptides possibly result from incomplete translation or degradation processes, since the construct used for initial mDNMT1 expression and purification comprised an N-terminal hexa-histidine tag. To minimize the amount of incomplete protein products that would be enriched in the following purification, we optimized the mDNMT1(731-1602) constructs for circularization by shifting the His-tag to the C-terminus.

After successful expression, the next critical step for high yields of recombinant protein after purification is protein extraction. The lysis method has to be efficient but still gentle enough to preserve the proteins function - especially when dealing with sensitive and low expressed proteins like DNMT1. In order to optimize protein extraction we therefore compared cell lysis by sonification with disruption via French press (Figure 6A and 6B). Due to the low overall yield, mDNMT1 does not appear as a prominent band on the Coomassie-stained gel as we expected for an overexpressed recombinant proteins. Assuming similar amounts of overall protein that should be present in the consecutively generated samples, sonification seems to be less efficient for extraction of recombinant protein compared to usage of the French press. Moreover, the disruption of E.coli using French press has been reported to preserve the biological activity of susceptible proteins more efficiently than sonication [18]. Therefore we used the French press for further extraction of linear as well as circular mDNMT1.

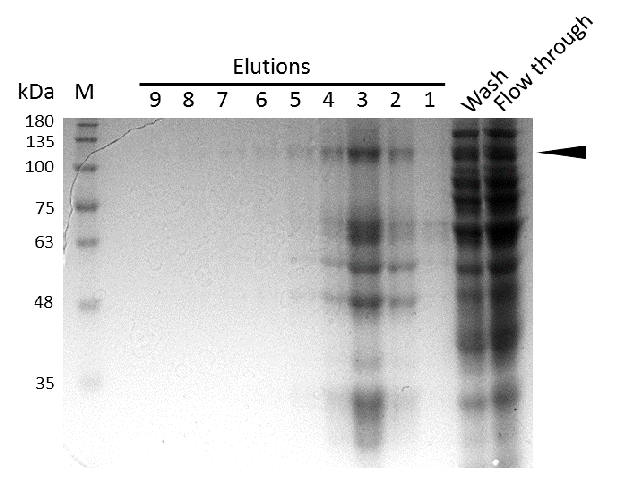

Further purification of the protein using a His-trap resulted in successful enrichment of mDNMT1f(731-1602) (Figure 6C). Corresponding eluates were pooled and further concentrated for use in functional assays.

mDNMT1(731-1602) expression in Rosetta (DE3) was performed over night at 15°C. Subsequently, the bacteria were lysed by sonification or French press and ultracentrifuged. After each step, samples were collected for analysis by SDS-PAGE. (Untransformed negative control (UnTra), intervals of cell disruption (1, 2), supernatant (SN)).

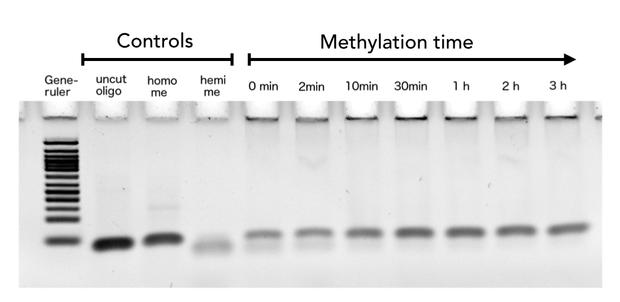

Activity and specificity of linear mDNMT1(731-1602)

After successful expression and purification of linear DNMT1, we characterized the proteins activity and specificity for hemi-methylated DNA by performing the methylation activity assay described above. To test the maintenance methylation activity of our linear DNMT1, we performed the methylation assay with different incubation times of DNMT1. We observe an increasing amount of completely methylated template over time (Figure 7), represented by increasing amounts of template that are unsusceptible towards SauAI cleavage. The truncated DNMT1 (731-1602) showed maximal methylation of the template after approximately 1/2 to 1hour. Therefore, our data agrees with efficiencies, that have been reported in literature for wild type and truncated versions of mDNMT1 [15] [16] .Overall, the reaction kinetics of the linear protein seem to be promising for later use in a PCR2.0, assuming that circularization of the protein will not ablate its function.

Purified linear mDNMT1(731-1602) was incubated with 40mer DNA template (see Figure4) for indicated times at 37°C. Subsequently the samples were digested with Sau3AI. Fragments were separated by PAGE and stained with ethidium bromide. (Homo me= homomethylated substrate, control for enzyme inhibition through methylation, Hemi me=hemimethylated substrate positive control for digest).

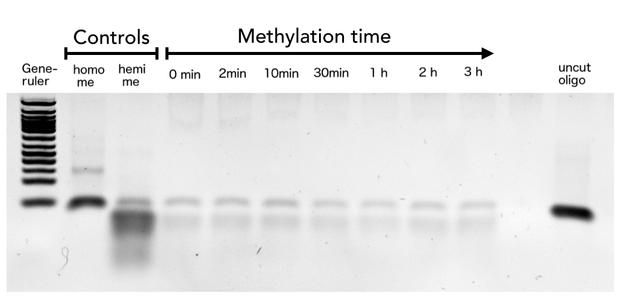

Purified linear mDNMT1(731-1602) was incubated with 40mer DNA template (see Figure4) for indicated times at 37°C. Subsequently the samples were digested with HpaII. Fragments were separated using gel-electrophoresis and visualized with ethidiumbromid staining. (Homo me= homomethylated substrate,control for enzyme inhibition through methylation, Hemi me=hemimethylated substrate positive control for digest).

In oder to be used in the targeted PCR2.0 mDNMT1 needs to be highly specific for hemi-methylated sites and should not display de novo methylation activity. Therefore, we included HpaII digestion in our assay to determine de novo methylation of CpG sites. The first results indicate that the purified mDNMT1(731-1602) does not exhibit de novo methylation activity (Figure 8). Even with increasing DNMT1 incubation time, HpaII is not repressed which indicates absence of de novo methylation. However, the analysis of the gel pictures is difficult since restriction efficiency of HpaII was not 100% as it can be seen from the hemimethylated control. Therefore, uncut template which is not resulting from unspecific methylation activity of the enzyme complicates quantitative analysis. Further tests, especially with the circularized protein will have to be performed to confirm these initial data.

Circular mDNMT1(731-1602) - The pivotal element of PCR2.0

Expression and purification of mDNMT1(731-1602) for circularization

After we succeeded in purifying active and specific linear mDNMT1, we went on with cloning, expression and purification of the circular DNMTs.

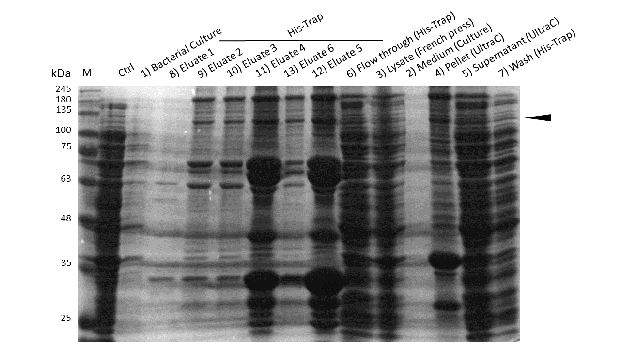

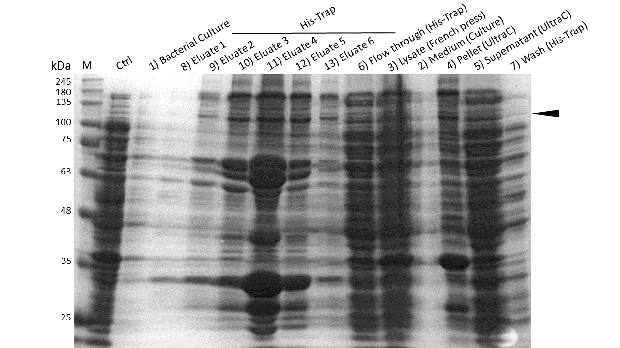

Expression and purification of mDNMT1(731-1602) for the intein as well as the sortase approach were conducted as they had been established for the linear DNMT1. Elutions from the His-Trap showed an enrichment and concentration of peptides that correlate with the expected molecular weight of the truncated mDNMT1(731-1602) (Figure 9A and 9B). Nevertheless, purification with a His-Trap alone does not seem to exclude a variety of impurities that either result from degraded mDNMT1 that still contains a His-Tag or unspecific binding to the affinity column. Advanced protocols as they were used by Song and collegues [19] for analysis of the proteins crystal structure are therefore including several more steps. Nevertheless, additional steps of purification increase the risk of reducing the overall protein yield and activity, necessitating greater amounts of starting material. Since the active protein should already be included and efficiently enriched in our sample despite of present impurities, we continued with the functional analysis of the sample.

Induction of Rosetta (DE3) and purification were performed as described above. After each step, samples were collected for analysis by Coomassie stained SDS-PAGE. Samples are numbered according to their chronology of collection. Arrow indicates mDNMT1(731-1602).

Induction of Rosetta (DE3) and purification were performed as described above. After each step, samples were collected for analysis by Coomassie stained SDS-PAGE. Samples are numbered according to their chronology of collection. Arrow indicates mDNMT1(731-1602).

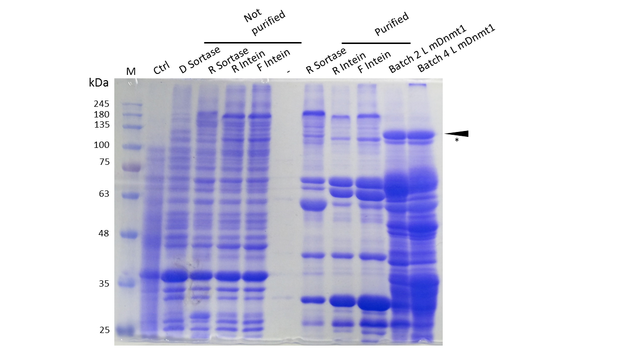

Expression and Purification of different constructs in Rosetta (DE3) was performed as described above. Unpurified as well as purified samples were collected for analysis by Coomassie stained SDS-PAGE. Ctrl indicates the untransformed control. D= no linker, R= Rigid linker, F=Flexible linker, L= linear. Arrow indicates peptides with molecular weight corresponding to mDNMT1(731-1602). Asterix indicates possibly spliced Intein constructs.

Our approach of heat-stabilization includes the testing of different linkers that had been calculated by our CRAUT Linker Software. We tested a flexible linker, consisting mostly of glycines and serines and a rigid linker, which was introduced to maximize stabilization of the protein through cicularization. Purification of the mDNMT1(731-1602) variants with different linkers for circularization was successful (Figure 10), but the yields were lower compared to different batches of linear mDNMT1(731-1602) that had been produced in a similar way. Interestingly, a shift between mDNMT1(731-1602) expressed from the intein construct compared to the sortase or linear versions was detected. Since protein circularization via inteins is an autocatalytic process that takes place inside the bacteria, this shift could possibly result from successful splicing activity of the inteins. The resulting product lacks Smt3 and is therefore approximately 30kDa smaller than its precursor (Figure 10, indicated by an asterix). Since intein splicing likely occurred, flexible- and rigid-linked-DNMT1 could be circularized.

To prove circularization by inteins, we cooperated with the core facility Protein Analysis of the German Cancer Research Center (Dkfz.). In the facility, circularized and linear DNMT1 were extracted from a provided gel, digested with trypsin and analyzed by ESI mass spectrometry. Unfortunately, we do not have the final results yet but are confident to be able to present them at the jamboree.

As against that mDNMT1(731-1602) with sortase recognition sequences needs to be further processed before a circular protein is obtained. Unfortunately, TEV cleavage of the purified protein, which is necessary for subsequent circularization with sortase was not very efficient. Therefore sortase treatment did not yield in a detectable amount of processed mDNMT1(731-1602). Therefore, we fully concentrated on the promising intein approach for further mDNMT1(731-1602) circularization.

Thermal stability of circular mDNMT1(721-1602)

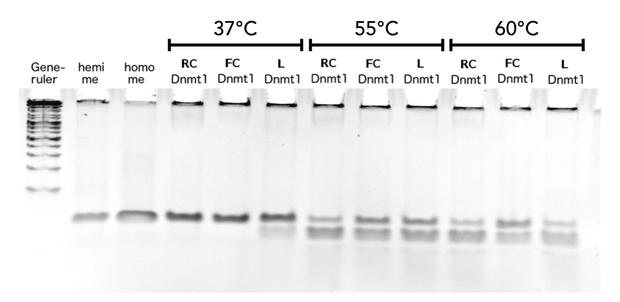

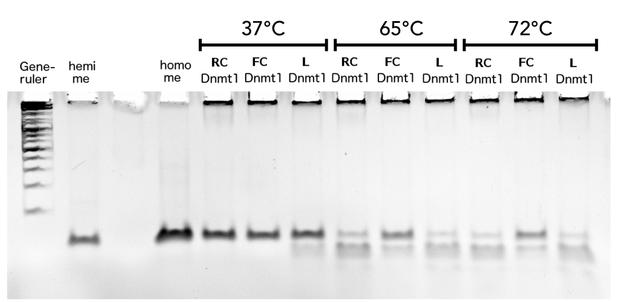

Circular DNMT1 with rigid linker (RC), circular DNMT1 with flexible linker (FC) and linear DNMT1 were heat shocked for 5 sec at 65°C and 72°C.Methylation after one hour was measured. A darker upper band for FC is even visible by eye, indication higher methylation activity.

In our final assay we examined the effect of an heat shock on the remaining activity of the different Dnmt1 enzymes to proof the ability of circular enzyme to withstand higher temperatures. We wanted to produce evidence for the feasibility of a PCR 2.0 using circularisation. Behaviour after heat treatment of pre-used linear Dnmt1 (L) was compared to Dnmt1 with rigid linker (RC) and flexible linker (FC) The proteins were exposed to temperatures between 55°C and 72°C, temperatures that would also be reached in a PCR. The heat shock was conducted for 5 sec and DNA substrate was added afterwards at 37°C for methylation to occur. Looking at the gel picture (Figure?) a darker upper band indicating more methylated substrate for the circular Dnmt1 with flexible Linker at all temperatures is even visible by eye, suggesting more remained stability. To confirm this results, the intensity of the gel bands were analysed using Image J. Figure ? highlights the remaining activity over temperature after normalisation to the control at 37°C the ration of methylated DNA was normalised to activity at 37°C. Indeed activity of circular DNMT1 with the flexible linker (black) is exciding the linear and ciruclar with rigid linker at least double. Very surprisingly, the methylation activity of circular DNMT1 with a flexible linker seems to increase with higher temperatures.

For significant evaluation, more data has to be collected. When applying Michael Menten kinetics , the methylation reaction for the controls already approaches saturation therefore the normalisation to the original activity might be defective. For further improvement of the assay, less volume of DNMT1 has to be taken for the enzyme reaction.

Discussion

Achievements and impact

Taking everything together we showed that introduction of inteins represents a feasable approach for circularisation of mDNMT1(731-1602). The post translational modification is conceivably increasing heat stability of the protein without impeding its specific methylation activity.

We proved that circularization with inteins is a rather easy method to increase heat stability of complex and sensitive proteins like mDNMT1(731-1602). In comparison, other methods for stabilization of proteins such as introduction of disulfide bonds require sophisticated structure analysis as well as non-physiological reaction conditions[20] [21].

The development and optimization of our CRAUT linker software has been an essential element in linking C- and N-terminus of mDNMT1(731-1602) while bypassing the active site of the protein and preserving its natural function. The two different linker compositions resulted in divergent heat stabilities of the protein. Therefore, software optimized linkers with designed properties have resulted in successful narrowing down of the infinite amount of possibilities to circularize mDNMT1(731-1602). Further experimental data of enzyme-specific inker variants will help to optimize the approach.

Circularized mDNMT1(731-1602) represents a valuable tool for the realization of a methylation maintaining PCR2.0. This foundational advance aims to enable broad functional analysis of DNA methylation patterns despite limited amounts of primary material. Even though detection of methylation patterns has been established in a high-throughput manner by using the principle of bisulfite sequencing, handling of limited amounts of primary material still represents a major challenge. Approaches including single molecule sequencing have been reported, but have not been established in an affordable and efficient manner yet [27]. Furthermore, these methods are limited to the detection of methylation patterns and do not allow functional analysis without complete analysis and cost-intensive synthesis. Therefore, our PCR2.0 aims to revolutionize the field of epigenetics by linking complex methylation patterns to their actual function. In vitro as well as in vivo experiments, requering large amounts of primary material will be feasible and more reproducible by using our PCR2.0.

A very interesting application for the pharmaceutical use of our PCR2.0 could be the large scale production of methylated gene therapy vectors. Since, methylation of gene transfer vectors has been reported to extend transgene product expression by lowering cellular immunogenicity, the efficiency gene therapies could be easily improved with our method. [22].

Further possible improvements

Additionally to the circularization of mDNMT1(731-1602), further approaches can be taken into account to realize a methylation maintaining PCR2.0. Those include further stabilization of the protein either by enhancing the hydrophobicity of the proteins core or direct links to limit possible conformations [23].

Another upcoming topic is the method of low temperature PCRs that exploit the function of helicases to segregate DNA strands. Even though these PCRs are not performed at high temperatures comparable to conventional PCRs, none of them has reached widespread establishment yet. Main reasons are that isothermal PCRs require either too long incubation times per cycle [24] or still exceed physiological temperatures of most enzymes [25].

A still challenging factor for PCR2.0 is the DNMT1 cofactor S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) that exhibits only low stability at high temperatures Matos, J. & Wong, C. S-adenosylmethionine: Stability and stabilization. Bioorg. Chem. 80, 71–80 (1987). During our experiments, there has not been observed any limitation due to this instability. Nevertheless, addition of the quite cheap methyl-donor after each cycle of replication could circumvent this problem until a more stable variant of the cofactor is available.

Moreover, the PCR2.0 reaction could be complemented with other enzymes such as UHRF1, that have been reported to increase the specificity of mDNMT1(731-1602) [19] Bashtrykov, P., Jankevicius, G., Jurkowska, R. Z., Ragozin, S. & Jeltsch, A. The UHRF1 protein stimulates the activity and specificity of the maintenance DNA methyltransferase DNMT1 by an allosteric mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 4106–15 (2014). The wild type DNMT1 is known to be associated with the replication complex for direction of its activity. Therefore design of an appropriate Polymerase-DNMT-fusion protein could imitate this connection and therefore further reduce stochastic methylation events. [26].

Overall, the iGEM Team Heidelberg’s intein toolbox in combination with the CRAUT linker software have contributed strongly to the foundational advance of establishing a PCR2.0.

References

[1] Watanabe, M., Yuzawa, H., Handa, N., & Kobayashi, I.. Hyperthermophilic DNA methyltransferase M.PabI from the archaeon Pyrococcus abyssi. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 72(8), 5367–75 (2006).

[2] Meissner, A. et al. Genome-scale DNA methylation maps of pluripotent and differentiated cells. Nature 454, 766–70 (2008)

[3] Vieille, C. & Zeikus, G. Hyperthermophilic enzymes: sources, uses, and molecular mechanisms for thermostability. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 65, 1–43 (2001).

[4] Antos, J. M., Popp, M. W.-L., Ernst, R., Chew, G.-L., Spooner, E., & Ploegh, H. L.. A straight path to circular proteins. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 284(23), 16028–36 (2009).

[5] Tam, J. P. & Wong, C. T. T. Chemical synthesis of circular proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 27020–5 (2012).

[6] Robertson, K. D. DNA methylation and human disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 6, 597–610 (2005).

[7] Jaenisch, R. & Bird, A. Epigenetic regulation of gene expression: how the genome integrates intrinsic and environmental signals. Nat. Genet. 33 Suppl, 245–54 (2003).

[8] Ehrlich, M.. Amount and distribution of 5-methycytosine in human DNA from different types of tissues or cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 10: 2709–2721 (1982).

[9] Lister, R. & Ecker, J. Finding the fifth base: genome-wide sequencing of cytosine methylation. Genome Res. 959–966 (2009).

[10] Bird, A.. DNA methylation patterns and epigenetic memory. Genes & Development 16, 6-21 (2002).

[11] Jaenisch, R., and Bird, A.. Epigenetic regulation of gene expression: how the genome integrates intrinsic and environmental signals. Nat Genet 33, 245-254 (2003).

[12] Weichenhan, D., and Plass, C.. The evolving epigenome. Human Molecular Genetics 22, R1 (2013).

[13] Robertson, K. D. DNA methylation and human disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 6, 597–610 (2005).

[14] Jurkowska, R. Z., Jurkowski, T. P. & Jeltsch, A. Structure and function of mammalian DNA methyltransferases. Chembiochem 12, 206–22 (2011).

[15] Song, J., Teplova, M., Ishibe-Murakami, S. & Patel, D. J. Structure-based mechanistic insights into DNMT1-mediated maintenance DNA methylation. Science 335, 709–12 (2012).

[16] Bashtrykov, P. et al. Specificity of Dnmt1 for methylation of hemimethylated CpG sites resides in its catalytic domain. Chem. Biol. 19, 572–8 (2012).

[17] Lee, C.-D., Sun, H.-C., Hu, S.-M., Chiu, C.-F., Homhuan, A., Liang, S.-M., Wang, T.-F. An improved SUMO fusion protein system for effective production of native proteins. Protein Science : A Publication of the Protein Society, 17(7), 1241–8 (2008).

[18] Benov, L. & Al-ibraheem, J. Disrupting Escherichia coli : A Comparison of Methods. 35, 428–431 (2002).

[19] Song, J., Rechkoblit, O., Bestor, T. H. & Patel, D. J. Structure of DNMT1-DNA complex reveals a role for autoinhibition in maintenance DNA methylation. Science 331, 1036–40 (2011).

[20] Betz, S. F. Disulfide bonds and the stability of globular proteins. 1551–1558 (1993).

[21] Bulaj, G. Formation of disulfide bonds in proteins and peptides. Biotechnol. Adv. 23, 87–92 (2005).

[22] Reyes-Sandoval, a & Ertl, H. C. J. CpG methylation of a plasmid vector results in extended transgene product expression by circumventing induction of immune responses. Mol. Ther. 9, 249–61 (2004).

[23] Vieille, C. & Zeikus, G. Hyperthermophilic enzymes: sources, uses, and molecular mechanisms for thermostability. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 65, 1–43 (2001).

[24] Vincent, M., Xu, Y. & Kong, H. Helicase-dependent isothermal DNA amplification. EMBO Rep. 5, 795–800 (2004).

[25] Xu, G. et al. Cross priming amplification: mechanism and optimization for isothermal DNA amplification. Sci. Rep. 2, 246 (2012).

[26] Vilkaitis, G., Suetake, I., Klimasauskas, S. & Tajima, S. Processive methylation of hemimethylated CpG sites by mouse Dnmt1 DNA methyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 64–72 (2005).

[27] Krueger, F., Kreck, B., Franke, A. & Andrews, S. R. DNA methylome analysis using short bisulfite sequencing data. Nat. Methods 9, 145–51 (2012).

"

"