Team:Marburg:Project:Tumor

From 2014.igem.org

CancerSURF

DARPins (Designed Ankyrin Repeat Proteins) serve as highly potential next generation protein drugs. They are derived from natural ankyrin repeat proteins that are the most common protein-protein interaction motif and predominantly found in eukaryotic proteins (Al Khodor et al. 2010). Also the genomes of various pathogenic or symbiotic bacteria and eukaryotic viruses contain several genes encoding ankyrin repeat proteins. Typically, two to four library modules, each corresponding to oneankyrin repeat of 33 amino acids with seven variable positions, are encased by two caps (N- and C-)(Figure 1A). Next to the resulting high diversity, these repeating modules reach an extremely small size compared to conventional IgG antibodies, preventing a higher tissue penetration. They show an absence of effector functions and can also exert allosteric inhibition mechanisms.

Figure 1: (A) Scheme of the DARPin library design.

B) Tetrameric StrepDARPidin

construct. Four DARPin

Ec1 molecules were fused via linker peptides to a

streptavidin protein. At the N terminus the Ec1

DARPin is fused to a polyhistidine-Tag (His-Tag)

and the C terminus prevents the linkage to the

streptavidin monomer. Adapted from: Stumpp, M. et al.

DARPins: a new generation of protein therapeutics.

Drug Discovery Today (2008).

Figure 1: (A) Scheme of the DARPin library design.

B) Tetrameric StrepDARPidin

construct. Four DARPin

Ec1 molecules were fused via linker peptides to a

streptavidin protein. At the N terminus the Ec1

DARPin is fused to a polyhistidine-Tag (His-Tag)

and the C terminus prevents the linkage to the

streptavidin monomer. Adapted from: Stumpp, M. et al.

DARPins: a new generation of protein therapeutics.

Drug Discovery Today (2008).

CancerSURF combines the scaffold of a tetrameric Streptavidin (Strep) to increase the specificity of DARPin Ec1 to detect a prominent tumor surface marker of many epithelium-derived cancer cells(like lung & colon cancer cells), called EpCAM (epithelial cell adhesion molecule) (Went et al. 2006). EpCAM is expressed by every epithelial cell on the basolateral side while being overexpressed on the surface by transformed tumor cells. We planned to fuse an EpCAM-binding DARPin Ec1 (Stefan et al. 2011) with a tetrameric Streptavidin increasing the local concentration of the construct for targeting EpCAM-positive tumor cells. In the next step, we wanted to combine the high density of epitopes offered by the filament of the bacterial flagellum as a scaffold with the modular advantages of a Streptavidin-Strep-Tag-system.

Figure 2: Transformation of epithelial cancer cells overexpressing EpCAM.

Figure 2: Transformation of epithelial cancer cells overexpressing EpCAM.

Production of a DARPin-Strep module for specific recognition of EpCAM in lung cancer cells

To address the goal of creating a CancerSURFer for efficient and rapid targeting of cancer cells, we first had to synthesize a Strep-DARPin fusion construct (StrepDARPidin). Template DNA for thetetrameric StrepDARPidin construct was commercially synthesized by IDT (Integrated DNA Technologies) and cloned into a pET-plasmide for overexpressionof the protein in E.coli BL21 (DE3). Streptavidin is not soluble when overexpressed and remains in inclusion bodies, so we had to apply a refolding protocol to (re)-gain StrepDARPidin in sufficient amounts (Howarth and Ting, 2008). After refolding the protein was purified in a two-step process: Ni-NTA-affinity purification and size-exclusion chromatography (Figure 3).The calculated protein mass of the monomeric StrepDARPidin is 31 kDa. The tetramer should have a size of 124 kDa and is visible above the highest marker line (116 kDa; Figure 3).

Figure 3:

Purification of StrepDARPidin. Size-exclusion chromatogram and

coomassie stained SDS-PAGE of purified StrepDARPidin. Upper SDS-PAGE:

Fractions taken from Ni-NTA purification. M: marker, L: lysate, FT: flow through,

W: wash, E: elution. Lower SDS-PAGE: Samples of peak fractions taken from size-exclusion

fractions. Samples on the right side have been cooked prior to loading showing the monomeric

<a href="http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1329000">StrepDARPidin</a>.

</span>

</div>

</html>

Figure 3:

Purification of StrepDARPidin. Size-exclusion chromatogram and

coomassie stained SDS-PAGE of purified StrepDARPidin. Upper SDS-PAGE:

Fractions taken from Ni-NTA purification. M: marker, L: lysate, FT: flow through,

W: wash, E: elution. Lower SDS-PAGE: Samples of peak fractions taken from size-exclusion

fractions. Samples on the right side have been cooked prior to loading showing the monomeric

<a href="http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1329000">StrepDARPidin</a>.

</span>

</div>

</html>

Protein containing fractions were analyzed on a coomassie stained SDS-PAGE and refolding was verified by incubating the eluate for 10 min at 95°C (Fig 3).

The peak fractions after size-exclusion were pooled and concentrated for further analysis.

In the next step StrepDARPidin binding specificity to EpCAM at lung and colon cancer cells was assayed to check functionality of the engineered StrepDARPidin. Colon cancer cells (Caco-2) and lung cancer cells (A549) which were known to highly express EpCAM (Maaser and Borlak, 2008) were treated with StrepDARPidin in serial dilutions. After washing they were incubated with anti-His-antibody-Alexa488 conjugate. Fibroblasts (3T3 wild typecells) were used as EpCAM-negative control. Fluorescence was quantified at 520 nm (Fig.4C)with a fluorometer.

Figure 4: (A) Immunofluorescent staining of Caco-2 and 3T3 cells incubated with

StrepDARPidin protein. Both cell lines were stained with Alexa555 (red) conjugated Phalloidin

(F-Actin) and Alexa488 (green) conjugated anti-His antibody (StrepDARPidin) in presence of

25µM StrepDARPidin. The nucleus was stained with DAPI (blue). (B) Immunofluorescent staining

of A549 cells incubated with StrepDARPidin protein. Cells were stained with Alexa555 (red)

conjugated Phalloidin (F-Actin) and Alexa488 (green) conjugated anti-His antibody (StrepDARPidin)

in presence of 25µM StrepDARPidin. The nucleus was stained with DAPI (blue). (C) Binding

specificity of StrepDARPidin to epithelial cancer cell lines. Flourenscence of Alexa488-coupled

anti-His-antibody in A549 and Caco-2 (epithelial) cells was normalized to 3T3 (interstitial)

cells. (D) Fluorescence intensities of Caco-2 and 3T3 cells in comparison.

Figure 4: (A) Immunofluorescent staining of Caco-2 and 3T3 cells incubated with

StrepDARPidin protein. Both cell lines were stained with Alexa555 (red) conjugated Phalloidin

(F-Actin) and Alexa488 (green) conjugated anti-His antibody (StrepDARPidin) in presence of

25µM StrepDARPidin. The nucleus was stained with DAPI (blue). (B) Immunofluorescent staining

of A549 cells incubated with StrepDARPidin protein. Cells were stained with Alexa555 (red)

conjugated Phalloidin (F-Actin) and Alexa488 (green) conjugated anti-His antibody (StrepDARPidin)

in presence of 25µM StrepDARPidin. The nucleus was stained with DAPI (blue). (C) Binding

specificity of StrepDARPidin to epithelial cancer cell lines. Flourenscence of Alexa488-coupled

anti-His-antibody in A549 and Caco-2 (epithelial) cells was normalized to 3T3 (interstitial)

cells. (D) Fluorescence intensities of Caco-2 and 3T3 cells in comparison.

The assay confirmed the optimal concentration of StrepDARPidin of 25 µM for the treatment of cancer cell lines (Figure 4C).

Next we wanted to investigate if StrepDARPidin can bind to epithelial cells. Therefore we used an immunofluorescence based approach. Caco-2 and A549 cells were grown on gelatin coated coverslips and incubated with 25 µM StrepDARPidin. As a negative control fibroblast cell line 3T3 was used. After fixation with formaldehyde, cells were permeabilized with Triton-X-100. The membrane-associated F-Actin was stained with phalloidin-rhodamine and the nucleus was stained with DAPI (Fig 4A, B). Anti-His-antibody-Alexa488 (green) conjugate was used for the staining of StrepDARPidin. Phalloidin conjugated with rhodamine(red)was used for staining of the F-Actin cytoskeleton to follow cell morphology. In Caco-2 and A549 cells a co-localization of StrepDARPidin with membrane-associated F-Actin could be shown (Fig 4A, B). Some unspecific His-staining was detected in the nucleus of all cell lines both in presence and absence of StrepDARPidin. In presence of StrepDARPidin both epithelial cell lines yielded the highest fluorescence intensity at the cell membrane. In Caco-2 cells the total fluorescence intensity ratio membrane/cytoplasm was 2.5x higher compared to 3T3 cells (Figure 4D).

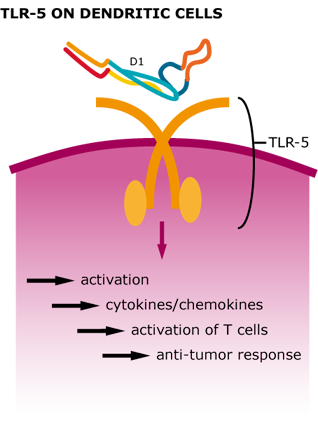

We could show that our tetrameric StrepDARPidin is capable of binding different EpCAM-positive cancer cell lineages, which already is a remarkable result. Now we wanted to further increase the local concentration of StrepDARPidin molecules and also integrate the activation of the innate immune system for further enhancement of our CancerSURFer. Bacterial surface proteins, such as Flagellin activate TLR5 (toll-like receptor 5) on dendritic cells leading to a stimulation of T helper cells. Therefore, employing bacterial flagellar filaments not only drastically increases the amount of StrepDARPidins present on the cancer cell surface but also leads to a stimulation of inflammatory reactions (Leigh et al. 2014).

Figure 5: Cellular response after TLR-5 activation by Flagellin.

Figure 5: Cellular response after TLR-5 activation by Flagellin.

Coupling StrepDARPidin to engineered Flagellin-D2-Strep

As described previously enhancing the local concentration of DARPin-molecules is crucial to allow a rapid and efficient targeting of cancer cells. Therefore, B. subtilis Flagellin was engineered carrying an insertion in the D1-domain replacing the small native loop (see SURFing for detailed information) with the S. typhimurium D2-domain and a Strep-Tag. The Flagellin-D2-Strep was used for generation of modified B. subtilis strains as well as overexpression in E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells (Figure 6A). As Flagellin tends to form polymers when overexpressed (this is a natural feature, it builds up the filament), it was co-purified with its cognate chaperone FliS forming a stable and stoichiometric complex on a size-exclusion column (Figure 6A). Fractions of the main peak were pooled and concentrated to a final volume of 500 μl for further analysis.

Figure 6: Purification of Flagellin-D2-Strep and binding assays with StrepDARPidin. (A) Size-exclusion

chromatogram of Flagellin-D2-Strep in complex with its chaperone FliS. Upper SDS-PAGE: Ni-NTA purification.

M: marker, L: lysate, FT: flow through, W: wash, E: elution. Lower SDS-PAGE: Samples of peak fractions

taken from size-exclusion fractions. (B)Streptavidin-and GST-interaction assay using purified Flagellin-D2-Strep

and Flagellin-Strep. (1) Strep-beads without protein. (2) Strep-beads with Flagellin-Strep immobilized. (3)

Strep-beads with Flagellin-D2-Strep. (4) GST-beads with Flagellin-Strep. (5) GST-beads with Flagellin-D2-Strep.

(C) Interaction of StrepDARPidin and Flagellin-D2-Strep visualized by competition assays. Soluble fractions:

(1) Flagellin-Strep. (2) Flagellin-D2-Strep. (3) Flagellin-Strep and StrepDARPidin. (4) Flagellin-D2-Strep and

StrepDARPidin. (5) StrepDARPidin. Insoluble fractions: (6) Flagellin-Strep and StrepDARPidin (1:5). (7)

Flagellin-D2-Strep and StrepDARPidin (1:5).(8) Flagellin-Strep and StrepDARPidin (1:1). (9) Flagellin-D2-Strep

and StrepDARPidin (1:1).

Figure 6: Purification of Flagellin-D2-Strep and binding assays with StrepDARPidin. (A) Size-exclusion

chromatogram of Flagellin-D2-Strep in complex with its chaperone FliS. Upper SDS-PAGE: Ni-NTA purification.

M: marker, L: lysate, FT: flow through, W: wash, E: elution. Lower SDS-PAGE: Samples of peak fractions

taken from size-exclusion fractions. (B)Streptavidin-and GST-interaction assay using purified Flagellin-D2-Strep

and Flagellin-Strep. (1) Strep-beads without protein. (2) Strep-beads with Flagellin-Strep immobilized. (3)

Strep-beads with Flagellin-D2-Strep. (4) GST-beads with Flagellin-Strep. (5) GST-beads with Flagellin-D2-Strep.

(C) Interaction of StrepDARPidin and Flagellin-D2-Strep visualized by competition assays. Soluble fractions:

(1) Flagellin-Strep. (2) Flagellin-D2-Strep. (3) Flagellin-Strep and StrepDARPidin. (4) Flagellin-D2-Strep and

StrepDARPidin. (5) StrepDARPidin. Insoluble fractions: (6) Flagellin-Strep and StrepDARPidin (1:5). (7)

Flagellin-D2-Strep and StrepDARPidin (1:5).(8) Flagellin-Strep and StrepDARPidin (1:1). (9) Flagellin-D2-Strep

and StrepDARPidin (1:1).

To investigate whether the purified Flagellin-D2-Strep is able to interact with Streptavidinin vitro prior to labeling intact filaments from

B. subtilis flagella, we used Streptavidin-pulldown assays to confirm the functionality.

We therefore immobilized purified Flagellin-D2-Strep and Flagellin-Strep on Streptavidin- and GST-beads (Figure 6B). Both engineered variants

of Flagellin bound to Streptavidin-beads but not GST and confirmed that the Strep-Tag is accessible and functional (Figure 5B, lanes 2 and 3).

We further wanted to know if our functional StrepDARPidin is capable of binding to the engineered Flagellin variants. This was the last and crucial step that had to be verified before docking of StrepDARPidin to the flagellar filaments could be performed. Purified proteins were mixed in different ratios and precipitation was observed. Samples from the supernatant (soluble fraction) and the pellet (insoluble fraction) were loaded on a SDS-PAGE showing that the pellet contained a huge amount of StrepDARPidin and the Flagellin variants (Figure 5C). We assume that the strong interaction of Streptavidin with the Strep-Tag leads to an aggregation of Flagellin-Strep variants followed by precipitation (Figure 5C, lanes 6-9).

The D2-Strep variant of Flagellin was also used for replacement of the native Flagellin in B. subtilis as described before (see SURFing for detailed information) to generate a strain exposing the Strep-Tag on the surface of the flagellar filament. In vitro assays confirmed that the Flagellin-D2-Strep was stable and functional but we had no information about the incorporation of the engineered Flagellin variant into the flagellar filament in vivo. Therefore, we inoculated swimming plates (containing 0.3 % agar) and swarming plates (containing 0.7 % agar) with B. subtilis wild type and D2-Strep cells. The mutant strain showed only slightly slower spreading on both plates, indicating that both single cellular and multi cellular movement is not affected much (Figure 6E, F). Additionally we employed negative staining transmission electron microscopy and could show that D2-Strep cells are as much flagellated as the wild type (Figure 6A, B). Finally, we can state that our engineered Flagellin variant D2-Strep is fully functional and incorporated into intact flagellar filaments. The last step, immobilizing StrepDARPidin on purified filaments, is currently finalized in the laboratory.

Figure 7: Electron micrographs of uranyl-acetate stained ''B. subtilis'' cells. (A) Whole cell of wild type strain

3610 (B) Whole cell of Flagellin-D2-Strep strain. Scale bar represents 1 μm. (C) Magnification of flagellar

filaments from 3610 wild type strain. Scale bar represents 100 nm (D) Magnification of flagellar filaments

from Flagellin-D2-Strepstrain. Scale bar represents 300 nm. (E) Swarming assay of both ''B. subtilis'' strains.

(F)Swimming assay of both ''B. subtilis'' strains.

Figure 7: Electron micrographs of uranyl-acetate stained ''B. subtilis'' cells. (A) Whole cell of wild type strain

3610 (B) Whole cell of Flagellin-D2-Strep strain. Scale bar represents 1 μm. (C) Magnification of flagellar

filaments from 3610 wild type strain. Scale bar represents 100 nm (D) Magnification of flagellar filaments

from Flagellin-D2-Strepstrain. Scale bar represents 300 nm. (E) Swarming assay of both ''B. subtilis'' strains.

(F)Swimming assay of both ''B. subtilis'' strains.

The CancerSURFer is a novel, modular and efficient method to target different cancer cell lineages and opens the gate for new applications in cancer treatment. The flagellar filament serves as a huge scaffold that can be loaded with different agents of ones own choice. By fusing the tetrameric Streptavidin to small molecules such as DARPin, a wide range of different applications is imaginable. Combining e.g. StrepDARPidin and fluorescent proteins fused to Streptavidin, cancer cells could be marked during clinical surgeries. Cytotoxic agents in combination with StrepDARPidin would directly lead to cancer cell lysis without a collateral damage to surrounding tissues making StrepDARPidin an imaginable antibody alternative for both future diagnostic and therapeutic perspectives.

Figure 8: Model for possible future applications in lung cancer treatment.

Figure 8: Model for possible future applications in lung cancer treatment.

Al-Khodor S, Price CT, Kalia A, Abu Kwaik Y (2010). Ankyrin-repeat containing proteins of microbes: a conserved structure with functional diversity.Trends Microbiol. 18, 132–139 10.1016

Howarth M, TingAY (2008).Imaging proteins in live mammalian cells with biotin ligase and monovalent streptavidin. Nature Protocols 3, 534 - 545 (2008).

Leigh ND, Guanglin Bian, Xilai Ding, Hong Liu, Semra Aygun-Sunar, Lyudmila G. Burdelya, Andrei V. Gudkov, Xuefang Cao (2014). A Flagellin-Derived Toll-Like Receptor 5 Agonist Stimulates Cytotoxic Lymphocyte-Mediated Tumor Immunity. PLoS ONE 9(1): e85587

Maaser K, Borlak J (2008). A genome-wide expression analysis identifies a network of EpCAM-induced cell cycle regulators.British Journal of Cancer (2008) 99,1635 – 1643.

Stefan N, Martin-Killias P, Wyss-Stoeckle (2011). DARPins Recognizing the Tumor-Associated Antigen EpCAM Selected by Phage and Ribosome Display and Engineered for Multivalency. J. Mol. Biol. (2011) 413, 826–843

Stumpp MT, Binz HK, Amstutz P. (2008). DARPins a new generation of protein therapeutics.Drug Discov. Today. Aug. 13(15-16):695-701.

Went P, Vasei M, Bubendorf L (2006).Frequent high-level expression of the Immunotherapeutic targetEp-CAM in colon, stomach, prostate and lung cancers. British Journal of Cancer (2006) 94, 128 – 135

"

"