Team:SUSTC-Shenzhen/Project

From 2014.igem.org

Project Description

a small overview to the whole big ideas

Introduction

In this project, we intended to establish a synthetic biology-based effective HIV-curing system with less side effects. The key goal is to integrate CRISPR/Cas system into human blood system to protect CD4+ cells against viral infection. The gRNA is designed to target the relative conserved regions in HIV viral genome and inactivate its biological activity. Since viral vectors seem to be of limited use in gene therapy strategies (e.g., potential pathogenicity), there is in dire need of a simple, efficient system for cell-specific delivery of nucleic acids. By using non-viral DNA delivery system such as A-B-toxin-GAL4 fusion protein, we can deliver plasmids encoding gRNA into the CD4+ cells and readily attack multiple HIV genome sites simultaneously with the most up-to-date knowledge of HIV epidemic.

Background

HIV (Human immunodeficiency virus)

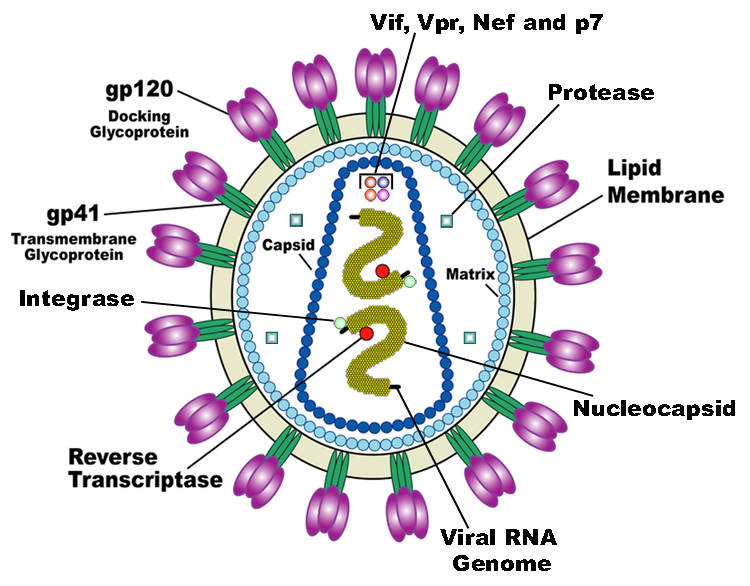

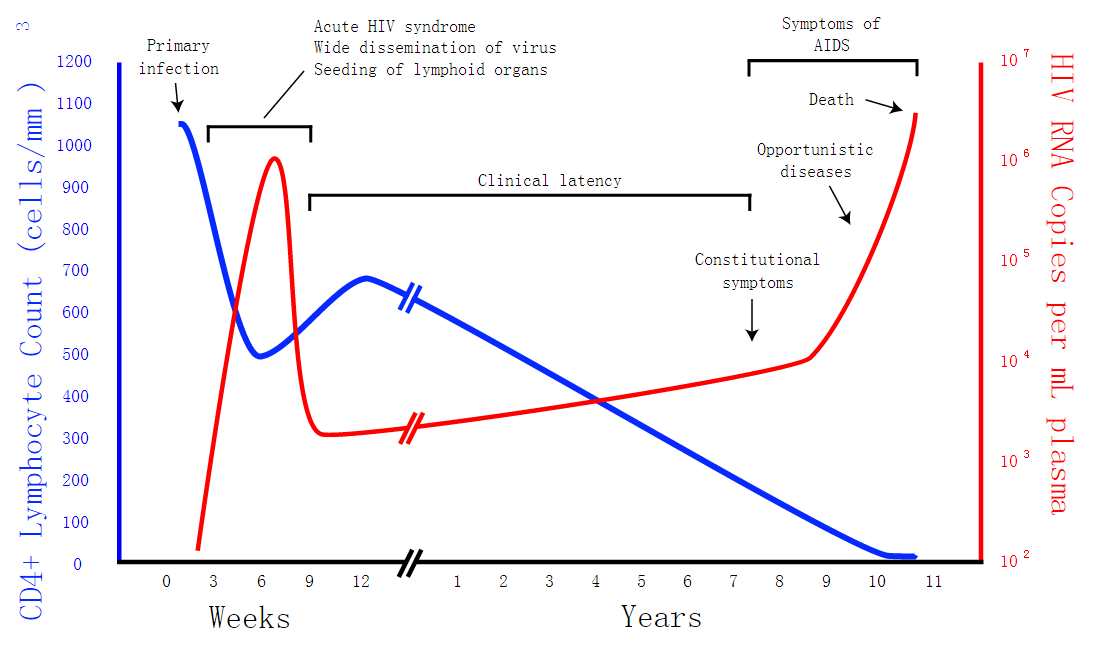

a) HIV is the trigger of the lethal disease AIDS. It replicates in and kills T cells, weakens human immune system and allows life-threatening opportunistic infection and cancer to thrive. HIV infects vital cells in the human immune system such as helper T cells (especially CD4+ T cells), macrophages, and dendritic cells. As a retrovirus, HIV reverse transcribes its genome and integrated it into the host cell genome after infection. Figure 1 illustrates the schematic structure of HIV virus (Source: Wikipedia).

Traditional therapies such as drug treatment can control the development of the disease but not eradicate the virus. The chronic inflammation and immune dysfunction caused by long-term chemotherapy and radiotherapy may also lead to non-AIDS morbidity and mortality (Kiem, Jerome, Deeks, & McCune, 2012). The process of reverse transcription is extremely error-prone, and the resulting mutations may lead to drug resistance or allow the virus to evade the body's immune system.

CRISPR/Cas system

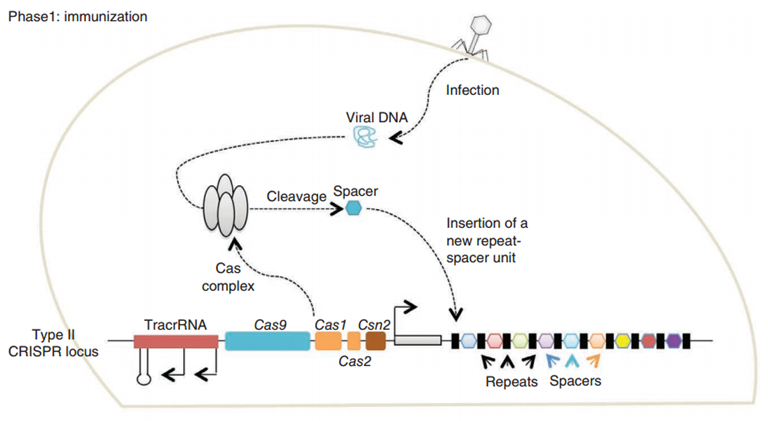

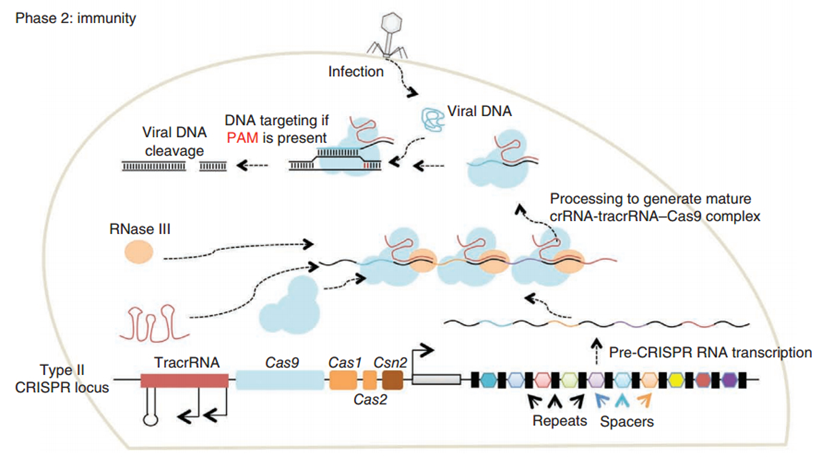

CRISPR/Cas (Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats/CRISPR-associated system) is originally a self-protecting mechanism in bacteria against external DNA such as virus genome or plasmids. It uses CAS complex to cut the external viral or plasmid DNA and integrating a short DNA segment into the CRISPR loci in the bacteria genome. This short DNA segment will be transcribed into pre-crRNA and bind to another CAS endonuclease called Cas9 with the help of tracrRNA. The Cas9 endonuclease cuts the external DNA in the existence of not only crRNA but also a special recognizing sequence at the 3’ end of the target DNA called PAM (Protospacer Adjacent Motif). When the same external DNA invades next time, the Cas9-tracrRNA-crRNA complex will recognize and cut it in order to destroy its biological activity. Figure 2 illustrates the mechanism of Type II CRISPR/Cas system in bacteria (Mali, Esvelt, & Church, 2013). The laboratories of Dr. George Church (Mali, Yang, et al., 2013) and Dr. Feng Zhang (Cong et al., 2013) have successfully developed the Type II CRISPR-Cas system for human cells, which lay the foundation for this project.

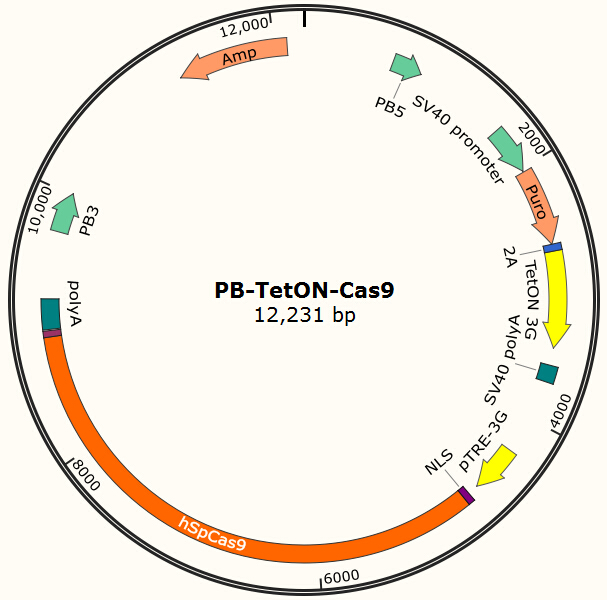

PiggyBac (PB) transposon system

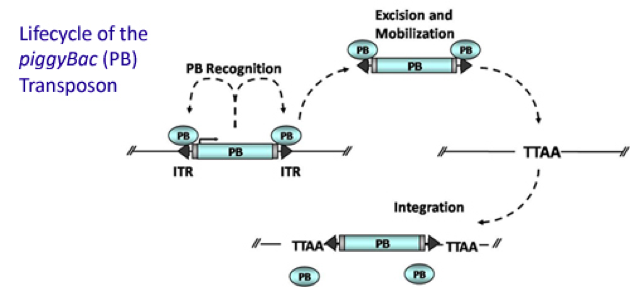

PiggyBac (PB) transposon is a mobile genetic element that efficiently transposes between vectors and chromosomes via a "cut and paste" mechanism but leave no “footprint”. PB transposase in this system recognizes the transposon-specific inverted terminal repeat sequence (PB5 & PB3 in Figure 5) located on both end of transposon vector and efficiently moves the contents from the original sites and efficiently integrates them into TTAA chromosomal sites. Figure 4 illustrates the working mechanism of PB transposon system (Source: Wikipedia; Author: Transposagenbio).

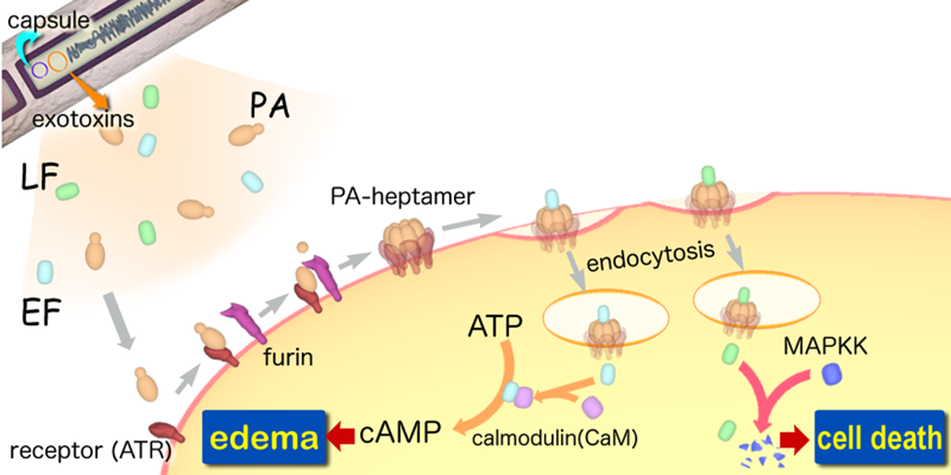

A-B toxin

A-B toxin are two-component exotoxin secreted by a number of pathogenic bacteria. The complexes contain two subunits called A and B. A subunit is the active portion that is poisonous to host cells. B subunit has a translocation domain and cell receptor binding domain, which helps the A subunit going into the cell through endosomes. Figure 4 shows how Anthrax toxin (a kind of A-B toxin) enters into human cells (Source: Wikipedia; Author: Y tambe).

Experiment design

See the full list of plasmids we used.

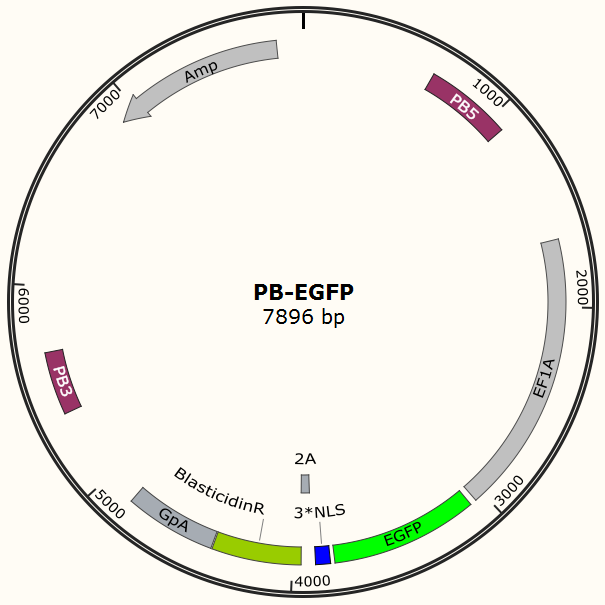

Constructing EGFP-Cas9 expressing cell lines

The program aims to endow the human cell the capacity of resisting the infection of HIV by introducing the CRISPR/Cas9 system into the human cell. To test the efficiency of the Cas9 and explore the optimal conditions of the system, we need a reporter to indicate whether the Cas9 functions and the targeted sites are cut off and destructed. So a cell line integrated with EGFP and Cas9 gene is firstly constructed in a similar way. We use PiggyBac transposon to transfect Hela cell for permanently expressing Cas9 protein. Once the proper gRNA is delivered into these cells, Cas9 binds to the gRNA and start to cut the complementary DNA strand. The vector design is based on Feng Zhang lab’s and Wei Huang lab’s plasmids.

Result Page for Cell Line Construction

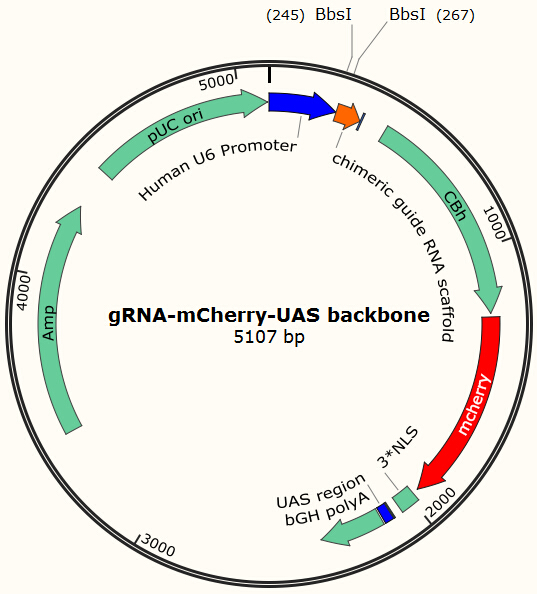

Transfecting the cell line with gRNA-encoding plasmid

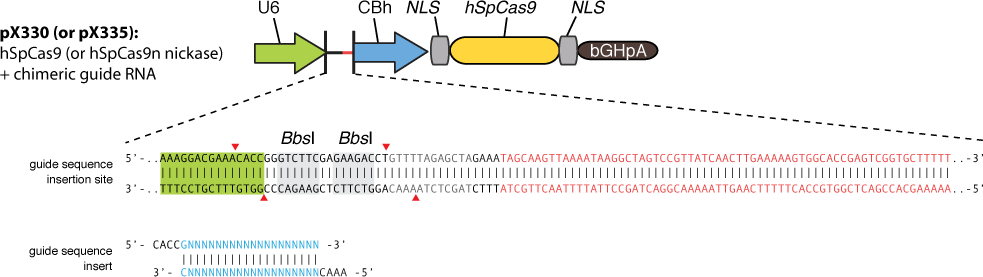

Cas9 uses gRNA, a 23nt short RNA fragment which binds to its complementary target and 'guide' Cas9 to cut the target DNA. We first check the efficiency of this system. We construct a plasmid based on Zhang Feng Lab’s pX330 plasmid that encodes a chimeric guide RNA scaffold and mCherry reporter gene followed by a NLS (nucleus leading sequence). It also contains 0, 2, 5 or 7 repeats of UAS sequences which are necessary for the vehicle’s recognition and binding (See Future applications – A-B toxin based gRNA shuttle for details).

The chimeric guide RNA scaffold is used to insert gRNA. We acquired the gRNA for EGFP from Wei Huang’s lab and put it into our constructed plasmid. Figure 8 shows the design of chimeric guide RNA scaffold (Cong et al., 2013).

In this way, with the ratio of reduced green fluorescence and the quantity of red fluorescence we can roughly obtain the efficiency of the CRISPR-Cas system we created. And finally, we reconstruct the plasmid but this time with the gRNA targeting HIV and test its efficacy.

For detailed information, see our gRNA-mCherry-UAS Carried Plasmids Design and Construction page.

Deliver gRNA plasmids by A-B toxin-based shuttle

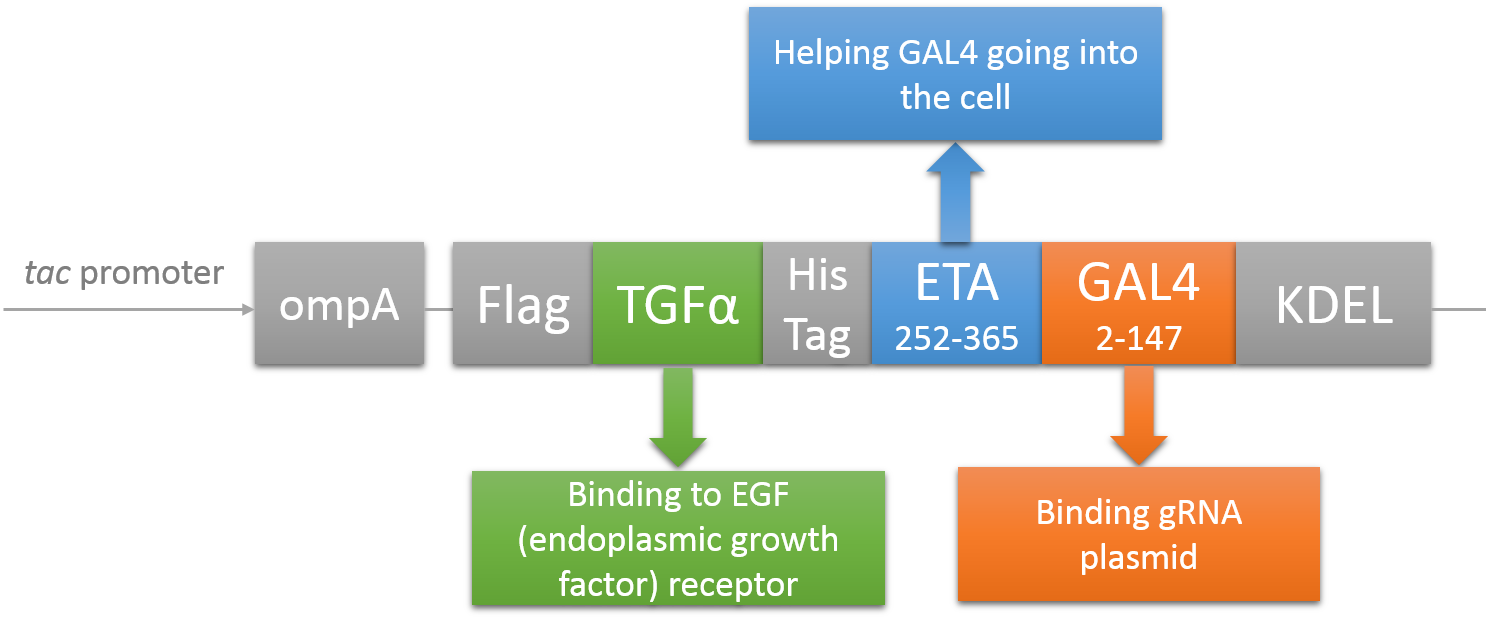

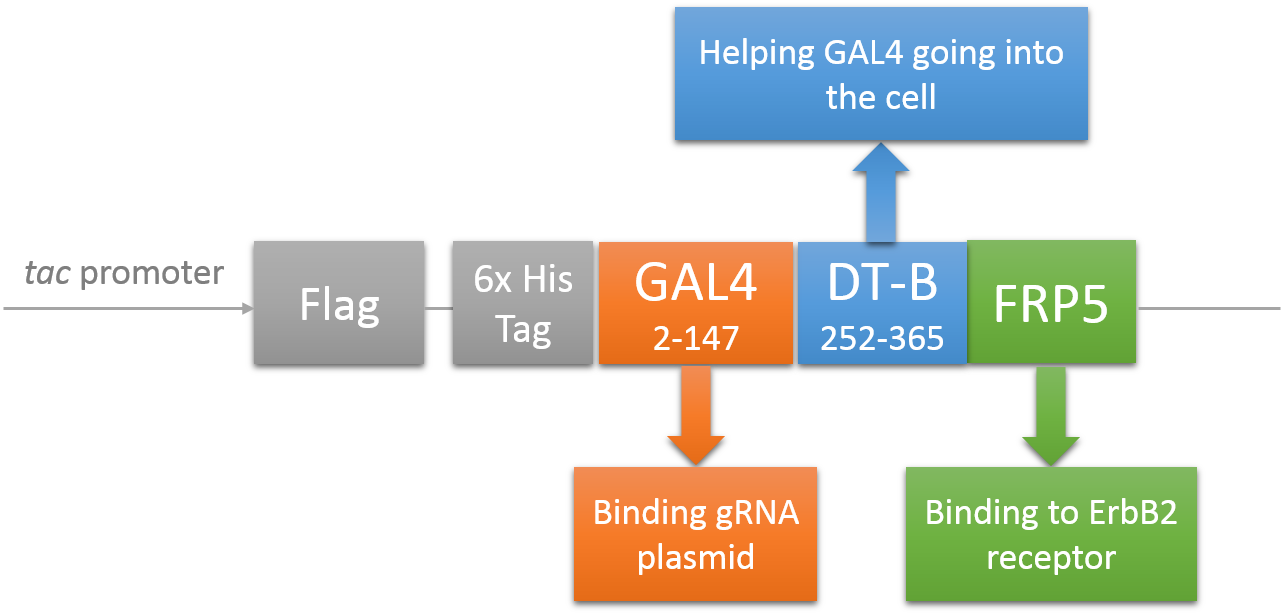

CRISPR/Cas system needs two essential parts for normal function: Cas9 and gRNA. We’ve seen a paper published in July that We choose a non-viral DNA delivery system which is based on modified A-B toxin. The chimeric fusion protein mainly comprises 3 parts: target cell-specific binding domain, a translocation domain and a nucleic acid binding domain. The target cell-specific binding domain recognizes the EGF (epidermal growth factor) receptors on the cell surface. The translocation domain enhances nucleic acid escape from the cellular vesicle system and thus to augment nucleic acid transfer. The nucleic acid binding domain, which derives from the yeast GAL4 transcription factor, can carry plasmids with UAS (Upstream Activation Sequence) sequences into cells in vivo. Several research groups from Germany to Taiwan (Gaur, Gupta, Goyal, Wels, & Singh, 2002) (Chen et al., 2000) (Fominaya, Uherek, & Wels, 1998) have achieved this goal. We are requesting the plasmid encoding TEG vehicle from a Germany research group. Figure 9 shows the schematic representation of the TEG fusion gene in the E.coli expression plasmid pWF47-TEG; Figure 10 shows the schematic representation of the GD5 fusion gene in the E.coli expression plasmid pSW55-GD5 (Wels, Winfried 63110 Rodgau (DE)).

For detailed information, see our A-B toxin-based shuttle page.

gRNA design

gRNA is a 23nt short RNA fragment (not include tracrRNA) which binds to its complementary target and 'guide' Cas9 to cut the target DNA. Since we would like to destroy the HIV virus inside human body, a gRNA sequence that matched a part of HIV conserved region best but have few off-target matches in the human genome is desired. However, designing a gRNA for a human-infective virus is difficult due to the very large difference in the genome size. For virus like HIV, it is even more difficult because HIV can mutate in a very high rate. So we change our goal to finding a group of specific quasi-conservative sequences (gRNA) which are able to target one or more species of HIV.

Our search for the sequence roughly followed the process described in George M. Church's paper (Mali, Yang, et al., 2013). We modified it slightly to fit our own purpose. We first used bioinformatics method to find the quasi-conservative regions in the HIV-1 whole genome reference library by NIH. From the candidates, we selected the region around 720bp from beginning of the genome (aligned), in the less-selected region slightly off the LTR.

We then used the online tools of Feng Zhang's Lab at MIT to find our desired gRNA composition. We also did some calculation based on phenomenological energy calculation to estimate the stability and effectiveness of our gRNA sequences (Hsu et al., 2013). The tool shows that almost no off-target binding will occur. BLAST was used to further confirm the results. We also analyzed the structure of the resulted gRNA, which shows an approximate free energy of -1.4kJ (Zuker, 2003).

For detailed information, see our gRNA design page.

Modeling

Our project is intended to treat retrovirus diseases.So we want to know how effective the CRISPR/Cas9 system is. In our model, we discuss about dynamic changes of different cells in a person’s body using Matlab and we take HIV for exmple. After theoretical analysis, symbol description, formula derivation and Matlab analysis, we can see how the system works and the influence the CRISPR/Cas system produces by the change of virus and cells in this model. It will help us to forecast the future applications of our project.If the environment doesn't change, we can stimulate the situation in Matlab for a short time. The result is that the CRISPR/Cas9 system will take effect.

For detailed information, see our Modeling page.

Safety

Our system has several built-in design to reduce the potential safety risks of the system utilization.

For detailed information, see our Safety page.

Future Perspectives

In vivo test to verify the efficiency and effectiveness of the system

Currently all our experiment design is based on in vitro conditions. However, our ultimate goal is to fight against HIV in vivo. A recent published paper in PNAS shows similar ideas with our experimental design and it also shows strong evidence for the effect of this system in other cell lines (Hu et al., 2014). So one of our important further work is to do in vivo test of our system.

Permanent implanting Cas9 gene into hematopoietic stem cells

Hematopoietic stem cells are the progenitor of all blood cells, including CD4+ T/B cells. It’s very difficult to extract all CD4+ T/B cells from the human blood system, doing the gene modification and then sent them back. Also, these cells can’t replicate, which means regularly gene modification should be done, which is unrealistic. Instead, one of our team members called Lin Le suggested to modify hematopoietic stem cells because all the offspring of the modified hematopoietic stem cells, including CD4+ T/B cells, carries our system, and it won’t loss since the renewal of CD4+ T/B cell will continue if the modified hematopoietic stem cells are still alive. A recent report (Holt et al., 2010) using engineered zinc-finger nucleases (ZFNs) to eliminate CCR5 in human CD34+ hematopoietic stem /progenitor cells (HSPCs) revealed the possibility to manipulate hematopoietic stem cells. Mouse model used in the report shows positive result after genome editing by ZFNs, which shows promising future for CRISPR/Cas9 mediated genome editing.

Using CRISPR/Cas system to integrate Cas9 into human cells

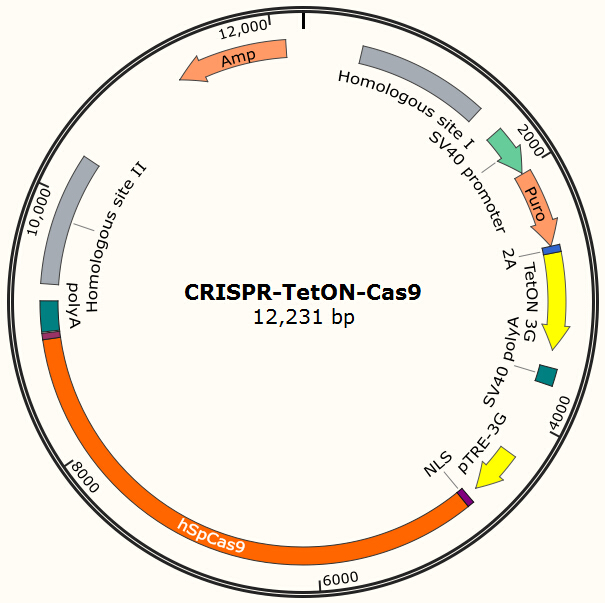

Our current plan uses Piggybac transposon system to deliver Cas9 into human cells. However, the integration site of Piggybac is non-specific, and it also has preferences for active transcribing sites, which may be normal or oncogene sites. Thus it is not ideal for clinical usage. However, the genome editing tool we used in this project (CRISPR/Cas system) has strong specificity for its target and the target can be designed to non-coding regions on human genome by carefully designed gRNA. One of the possible solution is to integrate homologous recombinant sites around Cas9. By transient transfect the cell with the Cas9 encoding plasmid shown in Figure 13 and the gRNA expression plasmid shown in Figure 7 and use doxycycline to induce the expression of Cas9, we can insert our system into the locus which does no harm to normal gene functions.

Using HIV-modified vector to specifically deliver Cas9 gene or gRNA plasmid into CD4+ cells

One of the main problems relating to our transfection system is non-directional, especially for A-B toxin based gRNA delivery because its target receptor is universally distributed on cell surface. However, the main group our system intends to protect is CD4+ cells because they are most susceptible to HIV. Interestingly, a paper published in 2009 reported a clinical trial that 2 X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD) patients received very positive treatment effect after gene therapy by using HIV-based lentivirus vector to transfect hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPCs) ex vivo (Cartier et al., 2009). So we think it’s promising to do gene therapy by using lentivirus vectors. There’s a saying in Chinese which is ‘Like cures like’. We think it explicitly expressed the idea of this approach.

Application in other retroviral diseases

The system designed by us can also be applied in treating other retrovirus diseases, such as Hepatitis B. We’ve designed gRNA for HBV and constructed target sequence plasmids to test its effectiveness (For the detailed information, see gRNA design page).

References

Cartier, N., Hacein-Bey-Abina, S., Bartholomae, C. C., Veres, G., Schmidt, M., Kutschera, I., . . . Aubourg, P. (2009). Hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy with a lentiviral vector in X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy. Science, 326(5954), 818-823. doi: 10.1126/science.1171242

Chen, T. Y., Hsu, C. T., Chang, K. H., Ting, C. Y., Whang-Peng, J., Hui, C. F., & Hwang, J. (2000). Development of DNA delivery system using Pseudomonas exotoxin A and a DNA binding region of human DNA topoisomerase I. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 53(5), 558-567.

Clontech. Tet-On 3G Inducible Expression Systems User Manual. http://www.clontech.com/TW/Products/Inducible_Systems/Tetracycline-Inducible_Expression/ibcGetAttachment.jsp?cItemId=17569&fileId=6832390&sitex=10021:22372:US.

Cong, L., Ran, F. A., Cox, D., Lin, S. L., Barretto, R., Habib, N., . . . Zhang, F. (2013). Multiplex Genome Engineering Using CRISPR/Cas Systems. Science, 339(6121), 819-823. doi: DOI 10.1126/science.1231143

Fominaya, J., Uherek, C., & Wels, W. (1998). A chimeric fusion protein containing transforming growth factor-alpha mediates gene transfer via binding to the EGF receptor. Gene Ther, 5(4), 521-530. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300614

Gaur, R., Gupta, P. K., Goyal, A., Wels, W., & Singh, Y. (2002). Delivery of nucleic acid into mammalian cells by anthrax toxin. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 297(5), 1121-1127. doi: Pii S0006-291x(02)02299-4 Doi 10.1016/S0006-291x(02)02299-4

Holt, N., Wang, J., Kim, K., Friedman, G., Wang, X., Taupin, V., . . . Cannon, P. M. (2010). Human hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells modified by zinc-finger nucleases targeted to CCR5 control HIV-1 in vivo. Nature Biotechnology, 28(8), 839-847. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1663

Hsu, P. D., Scott, D. A., Weinstein, J. A., Ran, F. A., Konermann, S., Agarwala, V., . . . Zhang, F. (2013). DNA targeting specificity of RNA-guided Cas9 nucleases. Nature Biotechnology, 31(9), 827-+. doi: Doi 10.1038/Nbt.2647

Hu, W., Kaminski, R., Yang, F., Zhang, Y., Cosentino, L., Li, F., . . . Khalili, K. (2014). RNA-directed gene editing specifically eradicates latent and prevents new HIV-1 infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1405186111

Kiem, H. P., Jerome, K. R., Deeks, S. G., & McCune, J. M. (2012). Hematopoietic-stem-cell-based gene therapy for HIV disease. Cell Stem Cell, 10(2), 137-147. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.12.015

Mali, P., Esvelt, K. M., & Church, G. M. (2013). Cas9 as a versatile tool for engineering biology. Nat Methods, 10(10), 957-963. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2649

Mali, P., Yang, L., Esvelt, K. M., Aach, J., Guell, M., DiCarlo, J. E., . . . Church, G. M. (2013). RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science, 339(6121), 823-826. doi: 10.1126/science.1232033

Zuker, M. (2003). Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res, 31(13), 3406-3415. doi: Doi 10.1093/Nar/Gkg595

"

"