Team:UCLA/Project/Spinning Silk

From 2014.igem.org

TEXT

TEXT

TEXT

TEXT

Processing Silk

Preparation for Silk Materials

Step 1: Degumming

Silk is comprised of two main proteins, fibroin and sericin. Fibroin is the structural protein of the silk and our protein of interest. Sericin serves as the ‘glue’ of the silk. Degumming separates and removes sericin and is an essential preparation step before dissolving the silk. We found that commercially degummed silk was not properly degummed for our purposes and this step had to be carried out in-lab.

Step 2: Solubilization

Getting significant amounts of silk (>0.25 grams) into solution requires the use of lithium bromide [1]. Protocols with less hazardous chemicals were attempted, yet none were able to reproduce results obtained using lithium bromide. The silk is cut into small pieces and dissolved in a scintillation vial at 60 degrees Celcius for 4 hours.

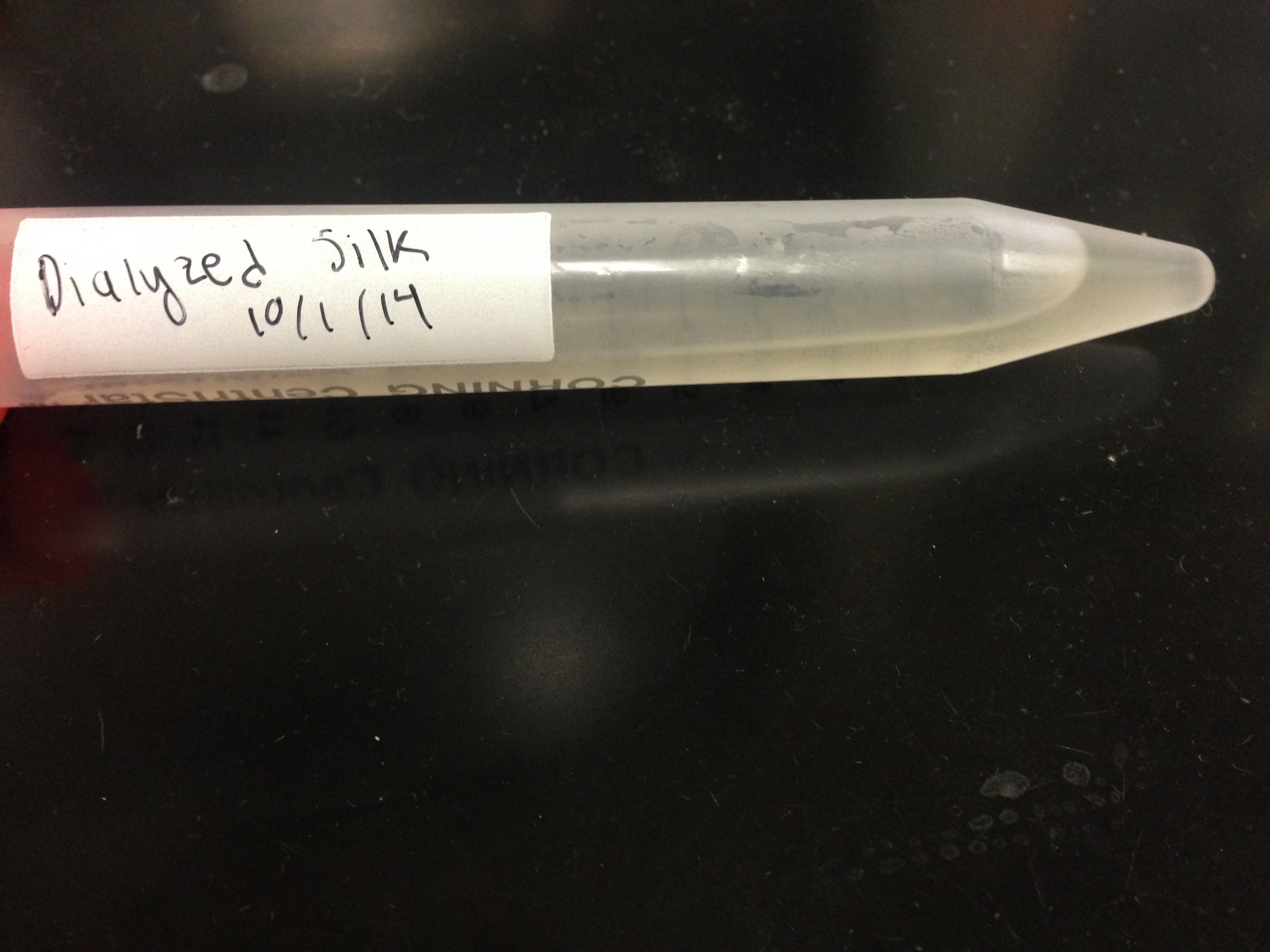

Step 3: Dialysis

Dialysis of the Fibroin-Lithium Bromide solution removes the lithium bromide, and results in an aqueous solution of the fibroin protein[1]. This solution can then be processed further in a variety of ways to achieve various structures and conformations of the silk protein.

Material - Silk Films

Silk films are the simplest way of processing the silk. The silk can be processed directly after dialysis. Dialyzed silk is simply dehydrated and the remaining silk aggregates into a film (protocol link). This simplicity may prove to be an asset as researchers investigate these films for next-generation medicine. The biodegradability of the films allows for technology like conformal electronics to be bio-integrated[2].

Material - Hydrogels

A silk hydrogel is a general term for a variety of ‘gel’ structures that can be created from silk. We chose to create a pH induced gel: the nature of this gel creates a chemically alterable microenvironment that can be tailored to optimize conditions for pharmaceuticals, tissues, or other biological agents. Biomedical applications of this technology could range from pain relievers integrated into a suture to tissue wound sealing.

Optional Processing: Lyophilization

Water can be completely removed from the dialyzed silk by the process of lyophilization, or freeze-drying. In this process, the solution is frozen by liquid nitrogen and is sublimated under vacuum for 2-3 days. This results in a pure silk powder that can be stored indefinitely. This silk powder can also be resuspended in solvents such as hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP) in preparation for spinning into a fiber.

Material - Fibers

Silk fibers are the most traditional form. Fibers can be formed from silk that has gone through the lyophilization process and has been resuspended in HFIP. From resuspension, the solution is ‘spun’ into fibers, as detailed below. Silk fibers as a biomedical device are intended to be used as the structural material for scaffolds to assist with re-engineered tissues. Silk scaffolds have the ability to be integrated into bones, cartilage, vascular tissue, and even skin [3].Spinning Silk

In order to form fibers from silk, soluble silk protein solutions must be much like how they are in natural spider spinnerets. The majority of spinning methods entail pushing, or extruding, silk solution through very thin channels. During this extrusion, shear forces on the silk solution cause the amino acids of the proteins to align in a way that allows the strong beta sheets of the silk structure to form. Multiple proteins are similarly aligned, causing separate proteins to interact and form larger structures.

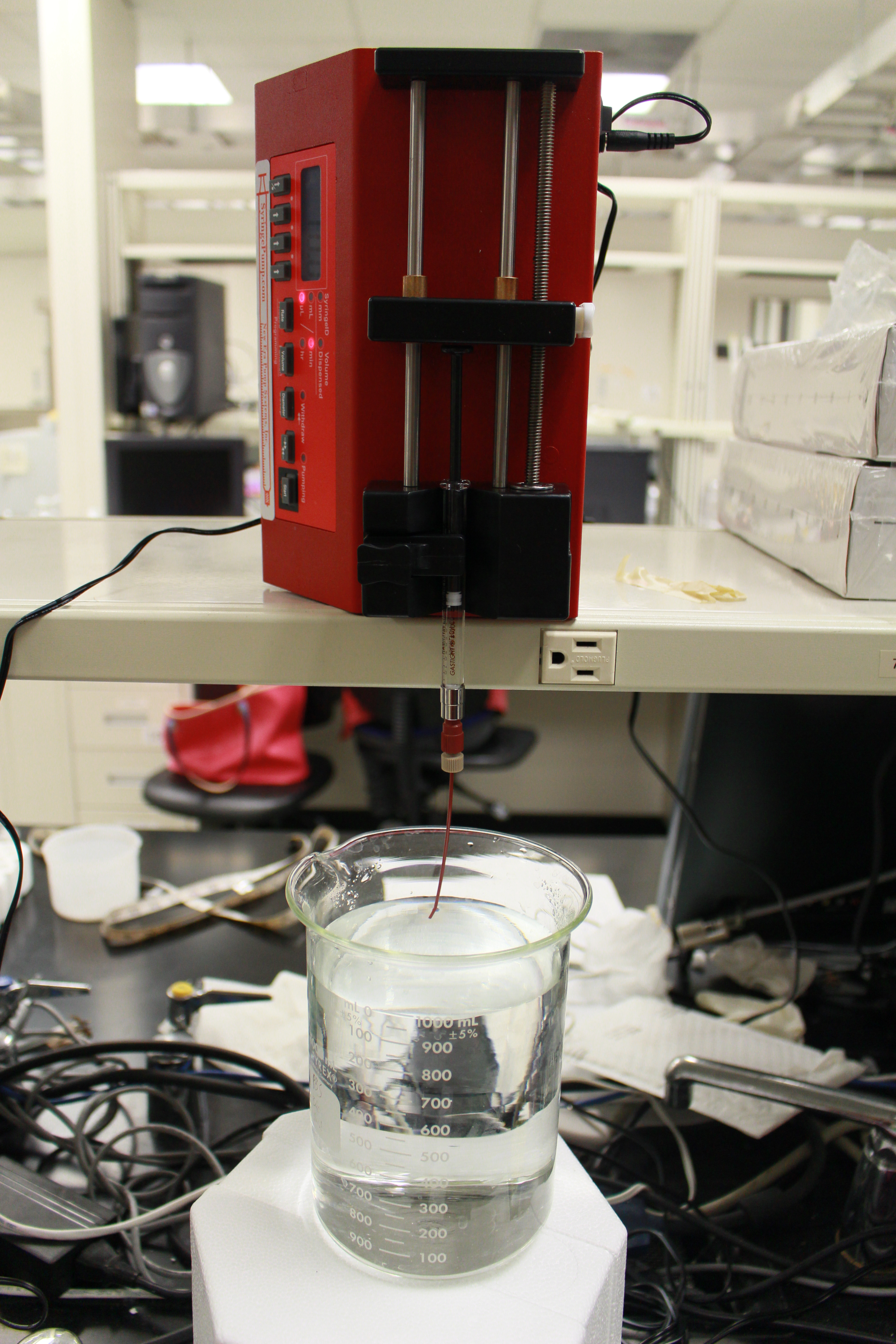

Syringe Extrusion

The standard method that we are using to produce silk fibers is syringe extrusion, in which a syringe pump forces silk dope through a small-diameter tube into a liquid isopropanol coagulation bath[1]. This method most directly emulates the process that spiders use. In a natural spider spinneret, silk solution produced in the spider's glands are forced through small-diameter spinnerets, and expelled as solid threads.

Centrifuge Extrusion

Another method that we are investigating is centrifuge extrusion, in which a column with a small-diameter channel is loaded with silk dope, and placed into a centrifuge tube containing the coagulation solution. The loaded column and tube are then centrifuged at high speeds, and the resulting centrifugal force extrudes the dope through the channel into the coagulation bath, causing a fiber to form. The extrusion column was designed this past summer by the UCLA iGEM team for rapid, small scale production of experimental fibers.

Rotary Jet Spinning

A final method for fiber production that we worked with is rotary jet spinning. Rotary jet spinning is very similar to centrifuge extrusion, in that the dope is spun at very high speeds and centrifugal force pushes the dope out of the channel. However, in rotary jet spinning, the dope is loaded into a reservoir that is mounted vertically onto a motor shaft. This method does not allow for the usage of a coagulation bath, as the reservoir holding the dope must be spun in air[4]. If the reservoir were to be spun in a liquid bath, the resultant turbulence in the bath would cause structural instability and destroy the apparatus.

Post-Spin Stretch

A very important part of creating fibers from expressed recombinant silk is the stretching of the fiber after it has been extruded. This can be observed in actual spiders, who tug on the silk threads they produce in order to stretch them. This stretching not only results in longer lengths of threads to work with, it confers extra strength and elasticity to the fibers [5].

References

[1]Teulé, Florence, Alyssa R. Cooper, William A. Furin, Daniela Bittencourt, Elibio L. Rech, Amanda Brooks, and Randolph V. Lewis. "A Protocol for the Production of Recombinant Spider Silk-like Proteins for Artificial Fiber Spinning." Nature Protocols 4.3 (2009): 341-55. Web.

[2]Kim, Dae-Hyeong, Jonathan Viventi, Jason J. Amsden, Jianliang Xiao, Leif Vigeland, Yun-Soung Kim, Justin A. Blanco, Bruce Panilaitis, Eric S. Frechette, Diego Contreras, David L. Kaplan, Fiorenzo G. Omenetto, Yonggang Huang, Keh-Chih Hwang, Mitchell R. Zakin, Brian Litt, and John A. Rogers. "Dissolvable Films of Silk Fibroin for Ultrathin Conformal Bio-integrated Electronics." Nature Materials 9.6 (2010): 511-17. Web.

[3] Rockwood, Danielle N., Rucsanda C. Preda, Tuna Yücel, Xiaoqin Wang, Michael L. Lovett, and David L. Kaplan. "Materials Fabrication from Bombyx Mori Silk Fibroin." Nature Protocols 6.10 (2011): 1612-631. Web.

[4]Badrossamay, Mohammad Reza, Holly Alice Mcilwee, Josue A. Goss, and Kevin Kit Parker. "Nanofiber Assembly by Rotary Jet-Spinning." Nano Letters 10.6 (2010): 2257-261. Web.

[5]An, Bo, Michael B. Hinman, Gregory P. Holland, Jeffery L. Yarger, and Randolph V. Lewis. "Inducing β-Sheets Formation in Synthetic Spider Silk Fibers by Aqueous Post-Spin Stretching." Biomacromolecules

"

"