Team:Lethbridge/project

From 2014.igem.org

Contents

Project

Figure 1. Confocal Image of HEK cells transfected with Lamp2B-clover construct. Description goes here.

Figure 2. Confocal Image of HEK cells transfected with Lamp2B-clover construct. Description goes here.

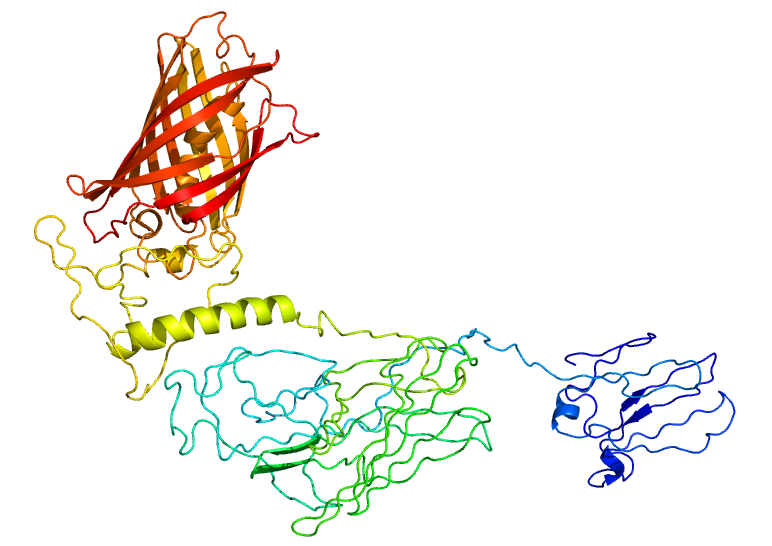

Figure 3. Construct design for the TEV protease. Description goes here.

Figure 4. RNA-IN/OUT construct design. Description goes here.

Background & Rationale

Astrocytes are abundant forms of glial cells located in the brain and spinal cord that serve to regulate cerebral blood flow and synapse function [1]. Central nervous system (CNS) injuries and neurodegenerative diseases are frequently accompanied by reactive astrogliosis, a process whereby astrocytes isolate damaged neural tissue, restrict inflammation, stimulate blood-brain barrier repair, and reduce further degeneration of surrounding brain tissue [2]. However, the formation of this obstructive “glial scar” also impedes future neural regeneration and axon remyelination and thus is a significant obstacle to rehabilitation in the CNS [3].

Interestingly, a recent study demonstrated the direct reprogramming of in vivo murine and cultured human reactive astrocytes to functional neurons using the retroviral expression of a single transcription factor, NeuroD1 [4]. Thus, NeuroD1 (if appropriately targeted to reactive astrocytes in damaged CNS tissue) has the potential to significantly improve current neural regeneration therapies. However, direct application of NeuroD1 to the human brain would not only be largely non-specific (and require the use of controversial viral delivery systems) but also excessively invasive. Consequently, the development of novel therapeutic delivery mechanisms is necessary to specifically target DNA, RNA, proteins, and other biologically relevant molecules to damaged or diseased neural cells. Microglia, another class of glial cell prevalent in the CNS, migrate to regions of neural damage and are the primary immune response in the CNS [5]. Their mobility, proximity to reactive astrocytes (and thus neural damage), and exosomal communication make them suitable candidates as potential delivery mechanisms for CNS injury-related rehabilitative therapies [6].

Objectives

Altogether, the aim of this study is to harness microglia as non-immunogenic carriers of neural tissue-specific therapeutic genes. Specifically, in an effort to promote functional recovery after CNS insult, these microglial cells will express a synthetic plasmid delivery system that exploits endogenous exosome production capabilities to deliver a neural reprogramming message. Our specific objectives include:

1) Generate microglial cells that package plasmids into exosomes and secrete them at regions of neural damage.

2) Use these engineered microglia to target stable plasmid DNA copies of the reprogramming factor gene NeuroD1 to regions of astrogliosis in a cell culture model of Traumatic Brain Injury. NeuroD1 will be selectively expressed in reactive astrocytes, thereby directly converting obstructive glial scars to neurons (replacing at least some of those lost to damage or disease) and reducing the inhibitory environment produced by the reactive astrocytes.

3) Design a novel antibiotic-free plasmid selection system that will allow generation of the NeuroD1-carrying plasmids while avoiding the introduction of antibiotic-resistance coding genes into human cells. Our proposed system will also minimize the size of our plasmid for ease of exosomal packaging.

Research Design & Methods

1) The rabies virus glycoprotein (RVG) is a small viral peptide that allows for CNS-specific uptake of exosomes. RVG, when fused to Lamp2B (an exosomal membrane protein), has proven to be a successful system for targeting siRNAs into CNS cells via exosomal delivery in mice [7]. Thus, to specifically target microglial exosomes (carrying therapeutic plasmids) to CNS cells, we will fuse RVG to the extra-exosomal N-terminus of Lamp2B and a Transcription Activator-Like Effector (TALE) DNA-binding protein to the C-terminus to anchor the plasmid within newly formed exosomes [8].

2) The therapeutic plasmid will encode the reprogramming factor NeuroD1 under the regulation of an astrocyte-specific promoter (Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein; GFAP), expression of which is strongly enhanced in reactive astrocytes. Thus, transcription of NeuroD1 will be specifically restricted to reactive astrocytes [9].

3) mRNA encoding Tobacco Etch Virus (TEV) protease will also be targeted to the microglial exosomes to induce the production of TEV protease within the target cells [10-11]. The active TEV protease will cleave a specific protein sequence located between the Lamp2B and TALE proteins of the designed protein scaffold, thereby releasing the TALE and the bound therapeutic plasmid into the cytosol of the target cell. A nuclear localization sequence (located in proximity to the TALE sequence) will target the bound plasmid to the nucleus, where NeuroD1 will be transcribed if (and only if) the target cell is a reactive astrocyte. The expression of NeuroD1 will induce reprogramming of the astrocyte into a new, functional glutamatergic neuron.

4) Antibiotic resistance is commonly used as a laboratory method for selecting bacteria containing a plasmid of interest. Besides the obvious implications of transferring antibiotic resistance genes to human cells, the large size of plasmids carrying antibiotic resistance markers is non-ideal for exosomal packaging. To bypass the use of antibiotic resistance markers during plasmid selection and to reduce the overall size of the therapeutic plasmid, the RNA-IN/OUT system will be used to regulate cell lysis via the production of T4 Holin and Endolysis proteins [12-13]. The RNA-OUT mRNA sequence (transcribed from the plasmid) binds to any mRNA with the RNA-IN sequence upstream of the ribosomal binding site (RBS), thereby occluding ribosomal binding and preventing translation of the mRNA. In this study, the RNA-IN sequence will be located before the RBS of the T4 Holin-Endolysin mRNA which, when translated in the absence of the RNA-OUT containing plasmid, will cause cell death.

5) The engineered microglial cells will be introduced into CNS tissue cultures that imitate sites of neurological damage and neuron loss. Several initial tests will be conducted with the engineered microglial cells including: the use of GFP in place of the TALE module of our plasmid delivery system to examine exosomal packaging function and proper membrane orientation; and the use of a GFP-producing plasmid with the RVG-Lamp2B-TALE system to test plasmid transfer and astrocyte-specific expression of GFP. Subsequently, the ability of the NeuroD1 reprogramming system described here to reprogram astrocytes will be tested via immunohistochemical detection of neuron-specific and glia-specific marker expression within the reprogrammed astrocytes.

Significance & Future Directions

Every year, the medical expenses, lost wages, and decreased productivity associated with stroke costs the Canadian economy $3.6 billion [14]. By 2040, Alzheimer’s Disease and other neurodegenerative disorders are predicted to cost the Canadian economy $293 billion per year [15]. The long-term objective of this proposal is to significantly improve current neural regeneration therapies in an effort to overcome the rehabilitative obstacles associated with CNS insults such as stroke, Alzheimer’s Disease, and traumatic brain injury in a non-invasive, cost-effective manner [4]. Furthermore, with future discoveries of other novel tissue-specific tags (similar to RVG) coupled with targeted DNA transmission therapies such as that discussed in this study, this system can potentially be harnessed to combat other tissue-specific disorders.

Ethics & Human Practice

In an effort to conduct our research in an ethically responsible manner, we are utilizing tissue cultures rather than live animals for our initial tests (in accordance with the 3Rs principle defined by the Canadian Council on Animal Care). Additionally, we have collaborated with the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) and health care professionals to evaluate current legislation and sentiments regarding cell and genetic therapies.

With regards to human practice, because microglia can be derived directly from patient bone marrow cells, this study has the potential to provide a method of personalized, non-immunogenic neural rehabilitation [16]. In addition, we are also addressing the growing prevalence of bacterial antibiotic resistance around the globe [17]. Our antibiotic-free plasmid selection system will help curb the spread of antibiotic resistance by reducing the potential for horizontal gene transfer of antibiotic resistance from lab strains to wild bacterial strains and by reducing the amount of antibiotics in lab waste and thus decreasing selective pressure towards antibiotic resistance.

References

[1] Barres, B.A. (2008). The mystery and magic of glia: a perspective on their roles in health and disease. Neuron, 60, 430-440.

[2] Sofroniew, M.V. (2005). Reactive astrocytes in neural repair and protection. The Neuroscientist, 11, 400-407.

[3] Fawcett, J.W. & Asher, R.A. (1999). The glial scar and central nervous system repair. Brain Research Bulletin, 49, 377-391.

[4] Guo, Z., Zhang, L., Wu, Z., Chen, Y., Wang, F., & Chen, G. (2014). In vivo direct reprogramming of reactive glial cells into functional neurons after brain injury and in an Alzheimer’s disease model. Cell Stem Cell, 14, 188-202.

[5] Aloisi, F. (2001). Immune function of microglia. Glia, 36, 165-179.

[6] Turola, E., Furlan, R., Bianco, F., Matteoli, M., & Verderio, C. (2012). Microglial microvesicle secretion and intercellular signaling. Frontiers in Physiology, 3, 149.

[7] Alvarez-Erviti, L., Seow, Y., Yin, H., Betts, C., Lakhal, S., & Wood, M.J.A. (2011). Delivery of siRNA to the mouse brain by systemic injection of targeted exosomes. Nature Biotechnology, 29, 341-347.

[8] Bogdanove, A.J. & Voytas, D.F. (2011). TAL effectors: Customizable proteins for DNA targeting. Science, 333, 1843-1846.

[9] Brenner, M., Kisseberth, W.C., Su, Y., Besnard, F., & Messing, A. (1994). GFAP promoter directs astrocyte-specific expression in transgenic mice. The Journal of Neuroscience, 14, 1030-1037.

[10] Kapust, R.B. & Waugh, D.S. (2000). Controlled intracellular processing of fusion proteins by TEV protease. Protein Expression and Purification, 19, 312-318.

[11] Batagov, A.O., Kuznetsov, V.A., & Kurochkin, I.V. (2011). Identification of nucleotide patterns enriched in secreted RNAs as putative cis-acting elements targeting them to exosome nano-vesicles. BMC Genomics, 12(Suppl 3):S18

[12] Mutalik, V.K., Qi, L., Guimaraes, J.C., Lucks, J.B., & Arkin, A.P. (2012). Rationally designed families of orthogaonal RNA regulators of translation. Nature Chem. Bio., 8, 447-454

[13] Young, R. (2002). Bacteriophage holins: deadly diversity. Journal of Molecular Microbiology and Biotechnology, 4(1), 21–36.

[14] Public Health Agency of Canada. (2009). Tracking heart disease and stroke in Canada. Retrieved from http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/2009/cvd-avc/pdf/cvd-avs-2009-eng.pdf

[15] Alzheimer Society of Canada. (2012). A new way of looking at the impact of dementia in Canada. Retrieved from http://www.alzheimer.ca/~/media/Files/national/Media-releases/asc_factsheet_new_data_09272012_en.pdf

[16] Hinze, A. & Stolzing, A. (2012). Microglia differentiation using a culture system for the expansion of mice non-adherent bone marrow stem cells. Journal of Inflammation, 9: 12.

[17] World Health Organization. (2014). Microbial resistance: global report on surveillance. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/drugresistance/documents/surveillancereport/en/

"

"