Team:Heidelberg/pages/background

From 2014.igem.org

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

| - | Inteins were discovered in 1990 when dissimilarities between the mature protein sequence of the yeast vacuolar ATPase (Vma1) and its corresponding mRNA | + | Inteins were discovered in 1990 when dissimilarities between the mature protein sequence of the yeast vacuolar ATPase (Vma1) and its corresponding mRNA were investigated. Surprisingly the mature protein had a lower molecular weight than expected from the encoding sequence, indicating the loss of one part of the protein after translation. |

Indeed, a region of 454 amino acids was found to be translated and subsequently removed from he Vma1 protein [[#References|[2]]] [[#References|[3]]]. Since the discovery of the Vma1 intein, over 600 different inteins have been reported in all three domains of life and viruses [[#References|[4]]]. | Indeed, a region of 454 amino acids was found to be translated and subsequently removed from he Vma1 protein [[#References|[2]]] [[#References|[3]]]. Since the discovery of the Vma1 intein, over 600 different inteins have been reported in all three domains of life and viruses [[#References|[4]]]. | ||

Revision as of 20:36, 17 October 2014

In the variety of proteins that exist, inteins are clearly among the most mysterious.

They behave in such a peculiarly way that scientists are still puzzle about their initial role in the host organisms and are even more astonished when discovering their endless seeming abilities.

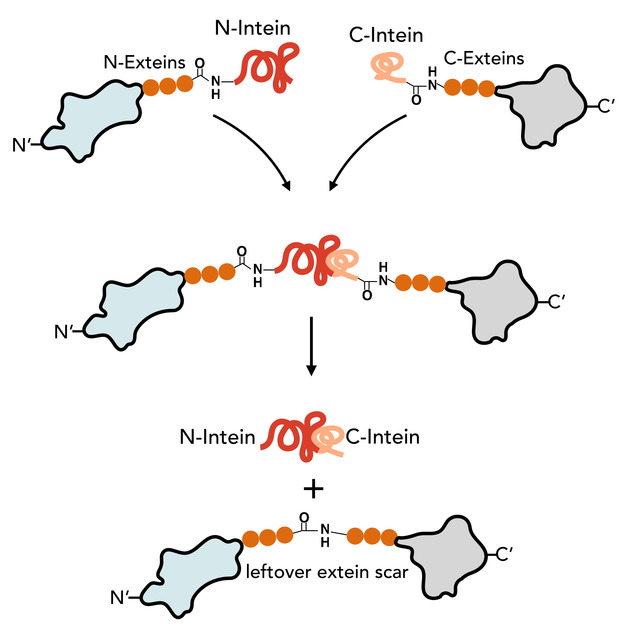

Inteins are integrated as extraneous polypeptide sequences into ordinary proteins. They do not contribute to the original protein function but perform an autocatalytic splicing reaction after protein translation. Analog to intron splicing on RNA level, this posttranslational modification was named protein splicing. Consequentially the protein segments were called inteins, derived from “internal protein sequence”, and the flanking protein chains exteins, “external protein sequences”. Inteins excise themselves out of the host protein while reconnecting the remaining N and C exteins via a new peptide bond. Despite this immense invasion the original protein regains its normal structure and function after splicing [1].

The N-Intein is fused to the C’ terminal end of the N-extein. Complementary, C-Intein is located at the N’ end of the C-extein. After assembly of the two intein fragments, a splicing reaction takes place, where the intein removes itself from the precursor protein and simultaneously ligates the exteins via a peptide bond.

Contents |

History

Inteins were discovered in 1990 when dissimilarities between the mature protein sequence of the yeast vacuolar ATPase (Vma1) and its corresponding mRNA were investigated. Surprisingly the mature protein had a lower molecular weight than expected from the encoding sequence, indicating the loss of one part of the protein after translation. Indeed, a region of 454 amino acids was found to be translated and subsequently removed from he Vma1 protein [2] [3]. Since the discovery of the Vma1 intein, over 600 different inteins have been reported in all three domains of life and viruses [4].

Dependent on the organism they belong to, the intein’s name consists out of the genus and species abbreviation followed by the host gene [5].

Evolution: Inteins as parasitic genes

Even after many years of research the initial role of inteins in their host organism remains still unclear. Many natural inteins contain a homing endonuclease (HEN) domain, an enzyme that cleaves DNA and includes new sequences at homing sites via homologous recombination or reverse transcription. This characteristic led to the perception of the intein as selfish DNA sequence - a gene generating copies of itself without an advantage for the host organism [6]. This allows horizontal gene transfer of inteins. [7]. Supporting this hypothesis: 27% of the inteins host proteins are related to DNA metabolism and involved in DNA replication or repair. This ensures expression of the inteins and the HEN domain during DNA replication, where they can take advantage of the DNA replication and repair system for introducing changes in the DNA [8].

However recent work on conditional protein splicing has shown sensitivity of some inteins to redox state, temperature and small molecules (reviewed in [9], [10]). This might be a sign for inteins having a role in post-translational protein regulation upon environmental signals. Inserted close to the catalytic core of the protein the protein remains inactive until the splicing reaction has taken place. Evolutionary said, once selfish inteins might have adapted due to selection pressure to be a beneficial mechanism for the host cell [8].

Classification and Structure

Inteins are divided into three groups: bifunctional (large) inteins, mini inteins and split inteins. Large inteins carry both a splicing domain and an endonuclease (HEN) domain whereas mini inteins lack the HEN domain [11]. The most promising inteins for biotechnology are split inteins, which are basically mini-inteins, but divided in two fragments and expressed separately with different proteins. After translation, they assemble with high affinity to be catalytic active. Split enzymes can be found naturally [12] but can also be artificially designed [13].

In our project we concentrated on split inteins, as they present a powerful tool for inserting posttranslational modifications in biotechnology. We have characterized the most promising inteins on our Intein database.

The structure of inteins contains several conserved motifs. The splicing domains are located at the N and C terminal ends. Before splicing can take place the intein rearranges itself from the linear form it has been translated into to a horseshoe like structure where the termini are broad in close proximity to form the catalytic core [14].

A detailed description of trans splicing reaction

In contrast to the mini and large inteins that mediate cis-splicing reactions, split inteins are responsible for trans-splicing and fusion of protein parts. The trans-splicing reaction can be divided into the following steps:

- N-Intein and C-Intein first assemble together to form a dimer like structure with a newly formed catalytic core next to the exteins.

- The tertiary structure of the intein, once correctly formed, facilitates an N→O/S acyl rearrangement at its N-terminal serine or cysteine residue. The result is an ester or thioester bond, respectively, between the side-chain and the peptide backbone of the N-extein.

- The two exteins are then linked by trans(thio)esterification involving the N-terminal serine or cysteine residue of the C-extein. The C-terminus of the N-extein is now covalently bound to the N-terminal side-chain of the C-extein, while its backbone still retains its normal peptide bond to the intein.

- The C-terminal asparagine of the intein undergoes self-cyclisation to form a succinimidyl moiety. The peptide bond between the intein and the extein is thereby broken, resolving the branched intermediate.

- In a final reaction, an O/S→N acyl shift results in the two exteins now being linked by an amide bond, indistinguishable from a ribosome-assembled fusion protein.

(as reviewed in [15])

Picture taken from [[#References|[16]]]

For intein efficiency not only the structure of the intein domain itself is important but also the nature of the flanking extein residues, as they are heavily involved in the splicing reaction. It has been shown, that the first residue has to be a nucleophilic amino acid, preferable Cysteine, Serine or Threonine. Effectiveness of the intein can be mold by changing the following amino acids [17].

Use of inteins in molecular biology and biotechnology

Due to their distinct characteristics intein are a powerful tool for molecular biology and biotechnology. Performing an autocatalytic reaction, the inteins are neither dependent on their host protein nor on any other additional substrate. This makes it them broadly applicable for in vivo and in vitro applications. [16].

Inteins have been used for protein purification, achieving a higher yield of protein due to more specific targeting. The production of semi-synthetic proteins and the attachment of synthetic groups is of huge interest for recombinant proteins. [16]. Split Intein-mediated Circular Ligation Of Peptides a ProteinS (SICLOPPS) is a method to produce circular peptides of eight amino acids length, which could be potent therapeutic drugs [18]. Inteins, fused to split fluorescent proteins as reporter and to the protein of investigation have been used to detect protein-protein interactions in vivo (reviewed in [10]). Nevertheless most of this applications are performed in vitro and do not exploit the full potential of inteins as regulatory element for post-translational modification. The iGEM Team Heidelberg employs this excellent mechanism of protein splicing to specifically change whole amino-acid sequences and thereby regulate proteins via (dis-) assembly, protein cleavage or circularization of enzymes in vivo. We provide a new foundational advance by introducing the full potential of post-translational modification and therefore a new dimension of genetic engineering to Synthetic Biology.

References

[1] Perler FB, Davis EO, Dean GE, Gimble FS, Jack WE, et al. (1994) Protein splicing elements: inteins and exteins–a definition of terms and recommended nomenclature. Nucleic Acids Res 22: 1125–1127

[2] Kane P.M., et al. Protein Splicing Converts the Yeast TEPI Gene Product to the 69-kD Subunit of the Vacuolar. 13253, (1990)

[3] Hirata, R. et al. Molecular structure of a gene, VMA1, encoding the catalytic subunit of H(+)-translocating adenosine triphosphatase from vacuolar membranes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 265 , 6726–6733 (1990)

[4] Perler, F. B. InBase : the Intein Database. 30, 383–384 (2002)

[5] Perler, F. B. et al. Protein splicing elements : inteins and exteins — a definition of terms and recommended nomenclature. 22, 1125–1127 (1994)

[6] Barzel, A., Naor, A., Privman, E., Kupiec, M. & Gophna, U. Homing endonucleases residing within inteins: evolutionary puzzles awaiting genetic solutions. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 39, 169–73 (2011)

[7] Pietrokovski, S. Intein spread and extinction in evolution. Trends Genet. 17, 465-472 (2001)

[8] Novikova, O., Topilina, N. & Belfort, M. Enigmatic distribution, evolution and function of inteins. J. Biol. Chem. (2014)

[9] Shah, N. H., and Muir, T. W. Inteins: nature's gift to protein chemists. Chem. Sci. 5, 446- 461 (2014)

[10] Topilina, N. I. & Mills, K. V. Recent advances in in vivo applications of intein-mediated protein splicing. Mob. DNA 5, 5 (2014)

[11] Eryilmaz, E., Shah, N., Muir, T. & Cowburn, D. Structural and Dynamical Features of Inteins and Implications on Protein Splicing. J. Biol. Chem. (2014)

[12] Carvajal-Vallejos, P., Pallissé, R., Mootz, H. D. & Schmidt, S. R. Unprecedented rates and efficiencies revealed for new natural split inteins from metagenomic sources. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 28686–96 (2012)

[13] Lin, Y. et al. Protein trans-splicing of multiple atypical split inteins engineered from natural inteins. PLoS One 8, e59516 (2013).

[14] Eryilmaz, E., Shah, N., Muir, T. & Cowburn, D. Structural and Dynamical Features of Inteins and Implications on Protein Splicing. J. Biol. Chem. (2014)

[15] Mills, K. V, Johnson, M. a & Perler, F. B. Protein Splicing: How Inteins Escape from Precursor Proteins. J. Biol. Chem. (2014)

[16] Mootz, H. D. Split inteins as versatile tools for protein semisynthesis. Chembiochem 10, 2579–89 (2009).

[17] Amitai, G., Callahan, B. P., Stanger, M. J., Belfort, G. & Belfort, M. Modulation of intein activity by its neighboring extein substrates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106, 11005–10 (2009).

[18] Tavassoli, A. & Benkovic, S. J. Split-intein mediated circular ligation used in the synthesis of cyclic peptide libraries in E. coli. Nat. Protoc. 2, 1126–1133 (2007).

"

"