Team:Austin Texas/photocage

From 2014.igem.org

(→Results) |

|||

| Line 73: | Line 73: | ||

<!-- WIKI CONTENT BEGINS --> | <!-- WIKI CONTENT BEGINS --> | ||

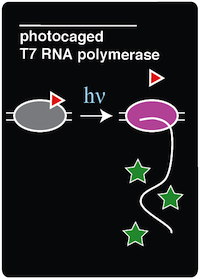

[[Image:Austin_Texas_Photocage_Card.png|right]] | [[Image:Austin_Texas_Photocage_Card.png|right]] | ||

| + | __TOC__ | ||

| Line 78: | Line 79: | ||

| - | |||

| - | + | <h1>Introduction</h1> | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

[[Image:Onbyreaction.png |left| 450px|thumb| Figure 1. The ONBY ncAA used for our photocaging project. When exposed to 365 nm light, the ONB group is released, resulting in a normal tyrosine amino acid.]] | [[Image:Onbyreaction.png |left| 450px|thumb| Figure 1. The ONBY ncAA used for our photocaging project. When exposed to 365 nm light, the ONB group is released, resulting in a normal tyrosine amino acid.]] | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

We recreated a light-activatable T7 RNA polymerase (RNAP) for the spatio-temporal control of protein expression. The light-activatable T7 RNAP was created by mutating a tyrosine codon at position 639 of a domain crucial for the polymerization of RNA during transcription. Y639 was mutated to an amber codon, allowing us to incorporate a ncAA at this position. We used ortho-nitrobenzyl tyrosine (ONBY), which is a "photocaged" ncAA (Figure 1). Thus, if our synthetase/tRNA pair works, position 639 should contain ONBY in place of tyrosine. This work is essentially a recapitulation of earlier work done by [Chou et al. 2010]. | We recreated a light-activatable T7 RNA polymerase (RNAP) for the spatio-temporal control of protein expression. The light-activatable T7 RNAP was created by mutating a tyrosine codon at position 639 of a domain crucial for the polymerization of RNA during transcription. Y639 was mutated to an amber codon, allowing us to incorporate a ncAA at this position. We used ortho-nitrobenzyl tyrosine (ONBY), which is a "photocaged" ncAA (Figure 1). Thus, if our synthetase/tRNA pair works, position 639 should contain ONBY in place of tyrosine. This work is essentially a recapitulation of earlier work done by [Chou et al. 2010]. | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

When the photocaged ONBY is incorporated at position 639, RNAP activity is inhibited. The polymerase can become activated only upon de-caging of the ONB group from the ONBY. This is accomplished by exposing the cells to 365 nm light. When exposed to 365 nm light, the ONB group is released, resulting in a normal tyrosine amino acid at position 639. T7 RNAP was selected because of its orthogonal nature, which allows us to selectively induce the expression of specific genes that are preceded by the T7 RNAP promoter. Because T7 promoters are not natively found in ''E. coli'', a gene downstream of a T7 promoter may be exclusively expressed through the introduction of 365 nm light. | When the photocaged ONBY is incorporated at position 639, RNAP activity is inhibited. The polymerase can become activated only upon de-caging of the ONB group from the ONBY. This is accomplished by exposing the cells to 365 nm light. When exposed to 365 nm light, the ONB group is released, resulting in a normal tyrosine amino acid at position 639. T7 RNAP was selected because of its orthogonal nature, which allows us to selectively induce the expression of specific genes that are preceded by the T7 RNAP promoter. Because T7 promoters are not natively found in ''E. coli'', a gene downstream of a T7 promoter may be exclusively expressed through the introduction of 365 nm light. | ||

| - | + | <h1>Background</h1> | |

Tyrosine residue 639 (Y639) was specifically targeted because it lies on a crucial position on the O-helix domain of T7 RNAP and has been proven to be essential for polymerization. (Chou et al. 2010) The Y639 residue in the O-helix is responsible for two major roles in the elongation stage of DNA polymerization. First, this tyrosine residue discriminates between deoxyribose and ribose substrates using the Tyrosyl-OH (Temiakov et al. 2004). Second, Y639 is responsible for moving newly synthesized RNA out of the catalytic site and preparing for the next NTP to be inserted (Achenbach 2004). These functions of the O-helix were shown to be essential through mutational analysis (Osumidavis 1994). Introducing a bulky group such as ONBY in place of tyrosine renders the enzyme nonfunctional in several ways. First, the native tyrosine-OH is not there anymore to coordinate Mg2+, which plays an essential role in discriminating between deoxyribose and ribose substrates. Additionally, because of the sterics of the ONBY molecule itself, it blocks incoming nucleotides from entering the active site. Because the loss of this tyrosine residue in the active site leads to a non-functional polymerase, Y639 proved to be a good candidate for incorporating a photocaged amino acid (Chou et al. 2010). | Tyrosine residue 639 (Y639) was specifically targeted because it lies on a crucial position on the O-helix domain of T7 RNAP and has been proven to be essential for polymerization. (Chou et al. 2010) The Y639 residue in the O-helix is responsible for two major roles in the elongation stage of DNA polymerization. First, this tyrosine residue discriminates between deoxyribose and ribose substrates using the Tyrosyl-OH (Temiakov et al. 2004). Second, Y639 is responsible for moving newly synthesized RNA out of the catalytic site and preparing for the next NTP to be inserted (Achenbach 2004). These functions of the O-helix were shown to be essential through mutational analysis (Osumidavis 1994). Introducing a bulky group such as ONBY in place of tyrosine renders the enzyme nonfunctional in several ways. First, the native tyrosine-OH is not there anymore to coordinate Mg2+, which plays an essential role in discriminating between deoxyribose and ribose substrates. Additionally, because of the sterics of the ONBY molecule itself, it blocks incoming nucleotides from entering the active site. Because the loss of this tyrosine residue in the active site leads to a non-functional polymerase, Y639 proved to be a good candidate for incorporating a photocaged amino acid (Chou et al. 2010). | ||

[[Image:Uncaging_of_ONBY.jpg | 300px|left|thumb| Figure 2. The caged T7 RNAP is decaged via exposure to 365 nm light. '''Chou et al. 2010''']] | [[Image:Uncaging_of_ONBY.jpg | 300px|left|thumb| Figure 2. The caged T7 RNAP is decaged via exposure to 365 nm light. '''Chou et al. 2010''']] | ||

| - | |||

Incorporation of ONBY at position 639 of T7 RNAP halts activity because of the bulky nature of ONBY (Chou et al. 2010). This ONB side group effectively renders T7 RNAP inactive. However, the bulky ONB group is able to be removed through irradiation with 365 nm light. The wavelength of light used to "decage" the amino acid proved to be another advantage of this system because 365 nm light is not toxic to the cell (Chou et al 2010). Once the ONB group is removed, a normal tyrosine residue is left in its place, restoring T7 RNA polymerase activity. | Incorporation of ONBY at position 639 of T7 RNAP halts activity because of the bulky nature of ONBY (Chou et al. 2010). This ONB side group effectively renders T7 RNAP inactive. However, the bulky ONB group is able to be removed through irradiation with 365 nm light. The wavelength of light used to "decage" the amino acid proved to be another advantage of this system because 365 nm light is not toxic to the cell (Chou et al 2010). Once the ONB group is removed, a normal tyrosine residue is left in its place, restoring T7 RNA polymerase activity. | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

In order to incorporate the ncAA into amberless E.coli (which is described '''[here]'''), a ''Methanocaldoccus jannaschii'' tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase/tRNA pair was previously mutated to selectively charge and incorporate ONBY. Six residues (Tyr 32, Leu 65, Phe 108, Gln 109, Asp 158, and Leu 162) on the original synthetase were randomized and the library was selected for its ability to charge ONBY while discriminating against other canonical amino acids. The resulting mutant ONBY synthetase contained five mutations (Deiters et al. 2006). The following are the residues that were mutated on the synthetase: Tyr32→Gly32, Leu65→Gly65, Phe108→Glu108, Asp158→Ser158, and Leu162→Glu162. The Asp158→Ser158 and Tyr32→Gly32 mutations are believed to result in the loss of hydrogen bonds with the natural substrate, which would disfavor binding to tyrosine. Additionally, the Tyr 32→Gly 32 and Leu 65→Gly 65 mutations are believed to increase the size of the substrate-binding pocket to accommodate for the size of the bulky o-nitrobenzyl group (Deiters et al. 2006). | In order to incorporate the ncAA into amberless E.coli (which is described '''[here]'''), a ''Methanocaldoccus jannaschii'' tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase/tRNA pair was previously mutated to selectively charge and incorporate ONBY. Six residues (Tyr 32, Leu 65, Phe 108, Gln 109, Asp 158, and Leu 162) on the original synthetase were randomized and the library was selected for its ability to charge ONBY while discriminating against other canonical amino acids. The resulting mutant ONBY synthetase contained five mutations (Deiters et al. 2006). The following are the residues that were mutated on the synthetase: Tyr32→Gly32, Leu65→Gly65, Phe108→Glu108, Asp158→Ser158, and Leu162→Glu162. The Asp158→Ser158 and Tyr32→Gly32 mutations are believed to result in the loss of hydrogen bonds with the natural substrate, which would disfavor binding to tyrosine. Additionally, the Tyr 32→Gly 32 and Leu 65→Gly 65 mutations are believed to increase the size of the substrate-binding pocket to accommodate for the size of the bulky o-nitrobenzyl group (Deiters et al. 2006). | ||

| - | + | <h1>Experimental Methods</h1> | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

In order to create an in vivo light-activated GFP expression system, two plasmids were constructed and transformed into amberless E.coli cells. The first plasmid contains the tRNA and synthetase pair, which is necessary to incorporate ONBY into the amber stop codon of the T7 RNAP. The second plasmid contains the coding sequence for T7 RNAP, which has a mutation on the Tyrosine 639 residue, and a GFP coding sequence bound to an upstream T7 promoter. Once these components were assembled by Gibson Assembly, the two plasmids were transformed via electroporation into aliquots of Amberless E.coli. | In order to create an in vivo light-activated GFP expression system, two plasmids were constructed and transformed into amberless E.coli cells. The first plasmid contains the tRNA and synthetase pair, which is necessary to incorporate ONBY into the amber stop codon of the T7 RNAP. The second plasmid contains the coding sequence for T7 RNAP, which has a mutation on the Tyrosine 639 residue, and a GFP coding sequence bound to an upstream T7 promoter. Once these components were assembled by Gibson Assembly, the two plasmids were transformed via electroporation into aliquots of Amberless E.coli. | ||

| Line 119: | Line 106: | ||

For this experiment, there were also other necessary control strains to test alongside the experimental strain. These controls included a T7-GFP construct with no amber stop codon in the O-helix (to serve as a positive control for expression with T7 polymerase), sfGFP amberless E.coli (to observe the expression of GFP by native polymerase), amberless E.coli (to serve as a cell background control), and LB supplemented with ncAA (to serve as a media background control). | For this experiment, there were also other necessary control strains to test alongside the experimental strain. These controls included a T7-GFP construct with no amber stop codon in the O-helix (to serve as a positive control for expression with T7 polymerase), sfGFP amberless E.coli (to observe the expression of GFP by native polymerase), amberless E.coli (to serve as a cell background control), and LB supplemented with ncAA (to serve as a media background control). | ||

| - | |||

After irradiation with light, these cells were allowed to grow overnight before taking fluorescent measurements. This additional growth was necessary to allow the "decaged" T7 RNAP to polymerize mRNA transcripts of the GFP coding sequence. | After irradiation with light, these cells were allowed to grow overnight before taking fluorescent measurements. This additional growth was necessary to allow the "decaged" T7 RNAP to polymerize mRNA transcripts of the GFP coding sequence. | ||

| Line 125: | Line 111: | ||

[https://2014.igem.org/Team:Austin_Texas/ONBY_detailed_methods Detailed Methods] | [https://2014.igem.org/Team:Austin_Texas/ONBY_detailed_methods Detailed Methods] | ||

| - | + | <h1>Results</h1> | |

[[Image:ONBY_GFP_Expression_After_Irradiation.jpg | 600px|thumb|left| Figure 3. GFP fluorescence observed after exposure to 365 nm light for the time indicated.'''reexport this figure''' ]] | [[Image:ONBY_GFP_Expression_After_Irradiation.jpg | 600px|thumb|left| Figure 3. GFP fluorescence observed after exposure to 365 nm light for the time indicated.'''reexport this figure''' ]] | ||

| Line 132: | Line 118: | ||

After this exposure, the cells were grown for an additional 16 hours, allowing the newly decaged T7 RNAP to transcribe the GFP reporter gene, which ultimately results in fluorescence. As can be seen in Figure 3, while the fluorescence background at time zero is not as low as we would like, there is a clear and dramatic increase in fluorescence that is directly dependent on the amount of time the culture was exposed to 365 nm light. This result is consistent with previous results using this system (Chou et al. 2010). | After this exposure, the cells were grown for an additional 16 hours, allowing the newly decaged T7 RNAP to transcribe the GFP reporter gene, which ultimately results in fluorescence. As can be seen in Figure 3, while the fluorescence background at time zero is not as low as we would like, there is a clear and dramatic increase in fluorescence that is directly dependent on the amount of time the culture was exposed to 365 nm light. This result is consistent with previous results using this system (Chou et al. 2010). | ||

| - | + | <h1>Discussion</h1> | |

The data from our photocage project provides strong evidence that we have, in fact, replicated the light-activated protein expression system that Chou et al. had constructed. | The data from our photocage project provides strong evidence that we have, in fact, replicated the light-activated protein expression system that Chou et al. had constructed. | ||

| Line 141: | Line 127: | ||

The replication of such a system provides the foundation for potential projects for our future iGEM teams. By replacing the GFP reporter with coding sequences for other proteins, we will be able to explore novel applications of light-activated protein expression. | The replication of such a system provides the foundation for potential projects for our future iGEM teams. By replacing the GFP reporter with coding sequences for other proteins, we will be able to explore novel applications of light-activated protein expression. | ||

| - | + | <h1>References</h1> | |

*Chou, C., Young, D. D. and Deiters, A. (2010), Photocaged T7 RNA Polymerase for the Light Activation of Transcription and Gene Function in Pro- and Eukaryotic Cells. ChemBioChem, 11: 972–977. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201000041 | *Chou, C., Young, D. D. and Deiters, A. (2010), Photocaged T7 RNA Polymerase for the Light Activation of Transcription and Gene Function in Pro- and Eukaryotic Cells. ChemBioChem, 11: 972–977. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201000041 | ||

*Deiters, A., Groff, D., Ryu, Y., Xie, J. and Schultz, P. G. (2006), A Genetically Encoded Photocaged Tyrosine. Angew. Chem., 118: 2794–2797. doi: 10.1002/ange.200600264 | *Deiters, A., Groff, D., Ryu, Y., Xie, J. and Schultz, P. G. (2006), A Genetically Encoded Photocaged Tyrosine. Angew. Chem., 118: 2794–2797. doi: 10.1002/ange.200600264 | ||

| Line 148: | Line 134: | ||

*J. C. Achenbach, W. Chiuman, R. P. G. Cruz, Y. Li, Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2004, 5, 321 –336. | *J. C. Achenbach, W. Chiuman, R. P. G. Cruz, Y. Li, Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2004, 5, 321 –336. | ||

*P. A. Osumidavis, N. Sreerama, D. B. Volkin, C. R. Middaugh, R. W. Woody, A. Y. M. Woody, J. Mol. Biol. 1994, 237, 5 – 19 | *P. A. Osumidavis, N. Sreerama, D. B. Volkin, C. R. Middaugh, R. W. Woody, A. Y. M. Woody, J. Mol. Biol. 1994, 237, 5 – 19 | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

<!-- WIKI CONTENT ENDS --> | <!-- WIKI CONTENT ENDS --> | ||

Revision as of 02:33, 17 October 2014

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

"

"