Team:TU Delft-Leiden/Project/Life science/EET

From 2014.igem.org

| Line 28: | Line 28: | ||

</p> | </p> | ||

<p> | <p> | ||

| - | In the ELECTRON TRANSPORT module we aimed to reproduce the results reported by Goldbeck et al. in a BioBrick compatible way. To our knowledge we are the first iGEM team that successfully BioBricked the mtr pathway. On top of that, we have succeeded to BioBrick <i>mtrCAB</i> under control of an adjusted T7lac promoter and | + | In the ELECTRON TRANSPORT module we aimed to reproduce the results reported by Goldbeck et al. in a BioBrick compatible way. To our knowledge we are the first iGEM team that successfully BioBricked the mtr pathway. On top of that, we have succeeded to BioBrick <i>mtrCAB</i> under control of an adjusted T7lac promoter and the <i>ccm</i> cluster under control of the pFAB640 promoter, a combination that was found to generate the largest maximal current (Goldbeck et al. (2013)). |

</p> | </p> | ||

Revision as of 14:21, 5 October 2014

Extracellular Electron Transport Module

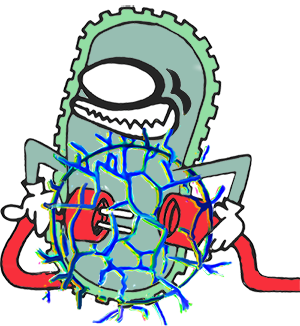

To facilitate extracellular ELECTRON TRANSPORT in E. coli we genetically introduced a heterologous electron transport pathway of the metal-reducing bacterium Shewanella oneidensis. The electron transfer pathway of S. oneidensis is comprised of c-type cytochromes that shuttle electrons from the inside to the outside of the cell (Yang et al., 2012). As a result, this bacterium couples the oxidation of organic matter to the reduction of insoluble metals during anaerobic respiration. There are several proteins that define the route for the electrons and thus are the major components of the electron transfer pathway (see figure x). Our key-player proteins are:

- CymA: an inner membrane cytochrome

- MtrA: a periplasmic decaheme cytochrome

- MtrC: outer membrane decaheme cytochrome

- MtrB: an outer membrane β-barrel protein

Now we have our so called Mtr electron conduit, but it will not function unless the multiple post-translational modifications are correctly carried out. Luckily, the cytochrome C maturation (Ccm) proteins help the conduit proteins to mature properly by providing them with heme, which is one of the requirements to carry and transfer electrons (Goldbeck et al., 2013).

Figure x. Major components of the S. oneidensis electron transfer pathway. Via a series of intermolecular electron transfer events, e.g. from menaquinol (QH) to CymA, from CymA to MtrA, and from MtrA via membrane pore MtrB to MtrC, the electrons find their way to the extracellular space. The electrons are derived from L-lactate oxidation by L-lactate dehydrogenase. NapC is a native E. coli cytochrome with comparable functionality to CymA.

Jensen et al. (2010) have described a genetic strategy by which E. coli was capable to move intracellular electrons, resulting from metabolic oxidation reactions, to an inorganic extracellular acceptor by reconstituting a portion of the extracellular electron transfer chain of S. oneidensis. However, bacteria expressing the Mtr electron conduit showed impaired cell growth. To improve extracellular electron transfer in E. coli, Goldbeck et al. (2013) used an E. coli host with a more tunable expression system by using a panel of constitutive promoters. Thereby they generated a library of strains that separately transcribe the mtr- and cytochrome ccm operons. Interestingly, the strain with improved cell growth and fewer morphological changes generated the largest maximal current per cfu (colony forming unit), rather than the strain with more MtrC and MtrA present.

In the ELECTRON TRANSPORT module we aimed to reproduce the results reported by Goldbeck et al. in a BioBrick compatible way. To our knowledge we are the first iGEM team that successfully BioBricked the mtr pathway. On top of that, we have succeeded to BioBrick mtrCAB under control of an adjusted T7lac promoter and the ccm cluster under control of the pFAB640 promoter, a combination that was found to generate the largest maximal current (Goldbeck et al. (2013)).

Cloning Strategy and Characterisation of this module

Cloning

Characterisation

"

"