Team:Freiburg/Content/Project/The light system

From 2014.igem.org

Lisaschmunk (Talk | contribs) |

|||

| (32 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

</head> | </head> | ||

<body> | <body> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="row category-row"> | ||

| + | <div class="col-sm-6"> | ||

| + | <div class="container-fluid" style="float: left"> | ||

| + | <div style="position: relative; float: right; margin-top: 4px;"> | ||

| + | <a href="https://2014.igem.org/Team:Freiburg/Project/Overview">Go back to Overview</div> | ||

| + | <div style="position: relative; float: left;"> <img class="img-no-border" style="max-width: 50px; margin-top:5px;" src=" https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2014/4/44/Freiburg2014_Navigation_Arrow_rv.png"> <!-- Pfeil rv--></a></div> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-sm-6"> | ||

| + | <div class="container-fluid" style="float: right"> | ||

| + | <div style="position: relative; float: left; margin-top: 4px;"> | ||

| + | <a href="https://2014.igem.org/Team:Freiburg/Project/Receptor">Read more about The Receptor</div> | ||

| + | <div style="position: relative; float: right;"> <img class="img-no-border" style="max-width: 50px; margin-top:5px;" src=" https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2014/9/95/Freibur2014_pfeilrechts.png"> <!-- Pfeil fw--></a></div> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

<section id="Project-Light-System-The-Light-System"> | <section id="Project-Light-System-The-Light-System"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

<h1>The Light System</h1> | <h1>The Light System</h1> | ||

<h2 id="Project-Light-System-Optogenetics">Optogenetics in Mammalian Gene Expression</h2> | <h2 id="Project-Light-System-Optogenetics">Optogenetics in Mammalian Gene Expression</h2> | ||

<div class="row category-row"> | <div class="row category-row"> | ||

<div class="col-sm-6"> | <div class="col-sm-6"> | ||

| - | <p>The term "Optogenetics" describes the use of genetically encoded, light-sensing proteins to modulate cellular function or even organismal behavior with high spatio-temporal resolution. In the past few years a large number of versatile light-controlled tools and devices have been developed in all | + | <p>The term "Optogenetics" describes the use of genetically encoded, light-sensing proteins to modulate cellular function or even organismal behavior with high spatio-temporal resolution. In the past few years a large number of versatile light-controlled tools and devices have been developed in all kinds of species, reaching from bacteria [1] to mammalian cells [2]. The introduction of microbial melanopsin into neurons [3] was the first optogenetic approach in mammalian cells and constitutes a milestone in neuronal research [4]. More recently, light-regulated tools have been successfully applied to control diverse signaling processes and gene expression in mammalian cells [2, 5]. Light-inducible gene expression systems follow the yeast two-hybrid principle, using photoreceptors, which allow a number of species to respond to environmental light conditions, as building blocks. In synthetically designed systems, light mediates the recruitment of a transcriptional activation domain to the DNA site. Therefore, either photoreceptors and their light-dependent specific interaction partners are fused to a transactivation domain or to a DNA binding domain, respectively, or light-induced homo-dimerization of photoreceptors is exploited to reconstitute a DNA binding domain. To date, spatio-temporal control over mammalian gene expression is provided by optogenetic gene switches, which are responsive to three distinct wavelengths in the blue, red and UV range [6].</p> |

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="col-sm-6"> | <div class="col-sm-6"> | ||

| - | < | + | <figure> |

| + | <a href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2014/d/d4/Freiburg2014_optogenetic_system.png"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2014/9/94/Freiburg2014_optogenetic_system_Thumbnail.png"> | ||

| + | </a> | ||

| + | <figcaption> | ||

| + | <p class="header"></em></p> | ||

| + | </figcaption> | ||

| + | </figure> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 23: | Line 49: | ||

<div class="row category-row"> | <div class="row category-row"> | ||

<div class="col-sm-6"> | <div class="col-sm-6"> | ||

| - | <p>In order to | + | <p>In order to choose the light system best suited for our experiments, we considered advantages and disadvantages of all three, such as possible toxic side effects, ease of handling and induction rate. UVB light-inducible gene switches show high induction rates, but UV light has a toxic effect on cells, and was therefore excluded [7]. In contrast, for the red and blue light-inducible systems, the light exposure has minimal toxic side effects. |

| + | </p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="col-sm-6"> | <div class="col-sm-6"> | ||

| - | <p> | + | <p> |

| + | Due to the longer wavelengths of red light, this system has the additional advantage of high tissue penetration, but on the other hand requires the addition of the small molecule compound PCB to work [8]. Both red and blue light systems are very sensitive to unintentional activation by room light and therefore require special care during handling [7]. Since this problem can be overcome by working under green safe light conditions, we considered both, blue and red light-inducible systems, as suited for our application. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 35: | Line 65: | ||

<div class="row category-row"> | <div class="row category-row"> | ||

<div class="col-sm-6"> | <div class="col-sm-6"> | ||

| - | <p>The blue light expression system used for the AcCELLarator capitalizes on the second LOV (Light-Oxygen-Voltage) domain of the protein phototropin of <em>Avena sativa</em> (AsLOV2). LOV domains are small photosensory peptides with up to 125 residues and are used by | + | <p>The blue light expression system used for the AcCELLarator capitalizes on the second LOV (Light-Oxygen-Voltage) domain of the protein phototropin of <em class="highlight-kursiv">Avena sativa</em> (AsLOV2). LOV domains are small photosensory peptides with up to 125 residues and are used by many higher plants, microalgae, fungi and bacteria to sense environmental conditions. LOV domains, such as the AsLOV2 domain, have been successfully employed in several designs for optogenetic tools. AsLOV2 is N- and C-terminally flanked by α helices, referred to as the Aα and Jα Helix, respectively.</p> |

| - | <p>In addition to the LOV2 domain, there are several other parts necessary for light induced expression of target genes. They can be separated into two main modules: <br /> One includes the previously mentioned LOV2 domain that is fused to a Gal4-DNA binding domain (Gal4DBD). This part is | + | <p>In addition to the LOV2 domain, there are several other parts necessary for light induced expression of target genes. They can be separated into two main modules: <br /> One includes the previously mentioned LOV2 domain that is fused to a Gal4-DNA binding domain (Gal4DBD). This part is constitutively bound to a specific DNA sequence, the Gal4-upstream activator sequence (Gal4UAS) nearby the promotor region of a target gene. <br /> The second part consists of an Erbin PDZ domain (ePDZ) that is fused to a VP16 domain. The VP16 domain can act as a transcriptional activator which recruits DNA polymerase to the gene of interest.</p></div> |

<div class="col-sm-6"> | <div class="col-sm-6"> | ||

| - | <p>The interaction between ePDZ and the Jα helix of LOV2 is the key process of the system: While in the dark, Jα chain is not exposed, therefore, the ePDZ- | + | <p>The interaction between ePDZ and the Jα helix of LOV2 is the key process of the system: While in the dark, the Jα chain is not exposed, therefore, the ePDZ-VP16 domain cannot be recruited, and the gene of interest will not be transcribed. Upon illumination, the Jα chain of the LOV2-domain becomes accessible, enabling the second part of the light system, ePDZ fused to VP16, to bind to the Jα chain. VP16 recruits DNA polymerase, thereby leading to transcription of the gene of interest.</p> |

<figure> | <figure> | ||

<a href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2014/e/e0/2014Freiburg_Lov2system.png"> | <a href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2014/e/e0/2014Freiburg_Lov2system.png"> | ||

| Line 44: | Line 74: | ||

</a> | </a> | ||

<figcaption> | <figcaption> | ||

| - | <p class="header"> | + | <p class="header">Principle of the blue light inducible expression system based on the LOV2 domain of phototropin from the common oat <em class="highlight-kursiv">Avena sativa</em>.</p> |

</figcaption> | </figcaption> | ||

</figure> | </figure> | ||

| Line 58: | Line 88: | ||

<div class="row category-row"> | <div class="row category-row"> | ||

<div class="col-sm-6"> | <div class="col-sm-6"> | ||

| - | <p>Red light | + | <p>Red light inducible gene expression is based on the <em class="highlight-kursiv">Arabidopsis thaliana</em> proteins phytochrome B (PhyB) and the phytochrome-interacting factor 6 (PIF6). PhyB is a photoreceptor with an N-terminal photosensory domain, which autoligates its chromophore phytochromobilin (PCB). There are two different states of PhyB: Under red light (660 nm), isomerisation of the chromophore results in the constitution of the active P<sub>FR</sub> form of the protein, which can bind to PIF6. Far red light illumination leads to reversion back into the inactive P<sub>R</sub> form and to dissociation of PhyB and PIF6. To capitalize on this light dependent interaction, the N-terminal part of PhyB has been fused to the transactivation domain VP16 derived from the herpes simplex virus. Further, the N-terminal domain of PIF6 was engineered to bind to the tetR-specific operator tetO upstream of the minimal human cytomegalovirus immediate-early promoter P<sub>hCMVmin</sub> by fusion to tetR, which binds PIF6 to the DNA.</p></div> |

<div class="col-sm-6"> | <div class="col-sm-6"> | ||

<figure> | <figure> | ||

| Line 65: | Line 95: | ||

</a> | </a> | ||

<figcaption> | <figcaption> | ||

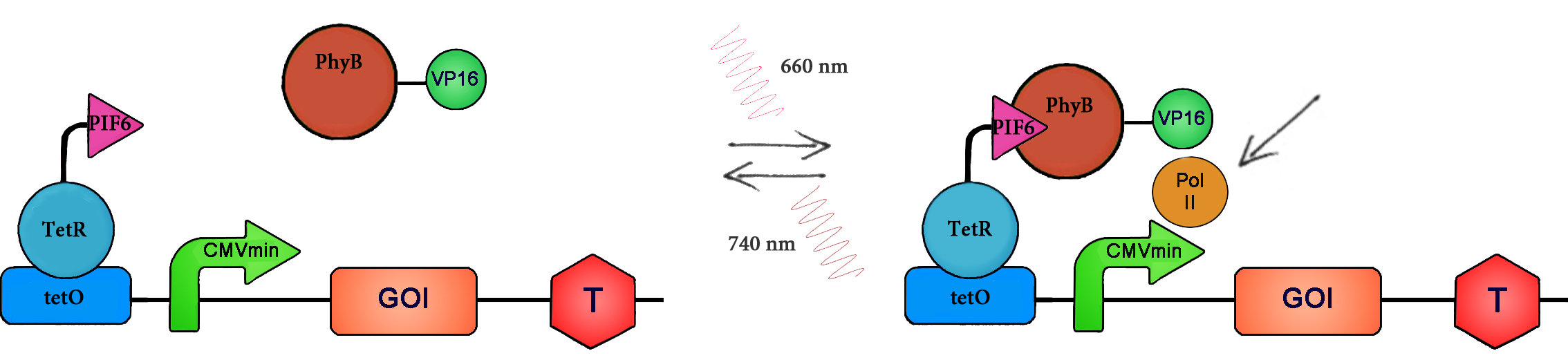

| - | <p class="header"> | + | <p class="header">Principle of the red light inducible expression system based on phytochrome B (PhyB) and the phytochrome-interacting factor 6 (PIF6) from the model organism <em class="highlight-kursiv">Arabidopsis thaliana</em>.</p> |

</figcaption> | </figcaption> | ||

</figure> | </figure> | ||

| Line 75: | Line 105: | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| - | <p> | + | <p>Both light systems are activated by photoexcitation: The LOV-system turns to the „ON“ state, leads to the recruitment and binding of ePDZ to the Jα helix and to induction of target gene expression. Under dark conditions, the system turns back into the „OFF“ state where transcription is terminated [9]. In the red light system, absorption of red light (660 nm) results in the recruitment of PhyB and the fused transcriptional activation domain to the promoter, which subsequently initiates transcription. The system can be immediately shut off by illumination with far red light (740 nm) [8].</p> |

| - | <p>In our application, The AcCELLerator, the target gene that is selectively induced by photoexcitation is mCAT-1, a murine cationic amino acid transporter. To explore the possibilities by using this | + | <p>In our application, The AcCELLerator, the target gene that is selectively induced by photoexcitation is mCAT-1, a murine cationic amino acid transporter. To explore the possibilities by using this transporter, visit the next page and find out why mCAT-1 is also termed “receptor”.</br><a href="https://2014.igem.org/Team:Freiburg/Project/Receptor">Read More about mCAT-1</a></p> |

<br> | <br> | ||

| + | <div class="row category-row"> | ||

| + | <div class="col-sm-6"> | ||

| + | <div class="container-fluid" style="float: left"> | ||

| + | <div style="position: relative; float: right; margin-top: 4px;"> | ||

| + | <a href="https://2014.igem.org/Team:Freiburg/Project/Overview">Go back to Overview</div> | ||

| + | <div style="position: relative; float: left;"> <img class="img-no-border" style="max-width: 50px; margin-top:5px;" src=" https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2014/4/44/Freiburg2014_Navigation_Arrow_rv.png"> <!-- Pfeil rv--></a></div> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-sm-6"> | ||

| + | <div class="container-fluid" style="float: right"> | ||

| + | <div style="position: relative; float: left; margin-top: 4px;"> | ||

| + | <a href="https://2014.igem.org/Team:Freiburg/Project/Receptor">Read more about The Receptor</div> | ||

| + | <div style="position: relative; float: right;"> <img class="img-no-border" style="max-width: 50px; margin-top:5px;" src=" https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2014/9/95/Freibur2014_pfeilrechts.png"> <!-- Pfeil fw--></a></div> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| - | <h2 id="mCAT-1-ListOfLiterature"> | + | <h2 id="mCAT-1-ListOfLiterature">References</h2> |

<ol class="two-columns small"> | <ol class="two-columns small"> | ||

| - | <li>Levskaya A, Chevalier AA, Tabor JJ, Simpson ZB, Lavery LA, Levy M, Davidson EA, Scouras A, Ellington AD, Marcotte EM, Voigt CA. Engineering Escherichla coli to see light. Nature | + | <li>Levskaya A, Chevalier AA, Tabor JJ, Simpson ZB, Lavery LA, Levy M, Davidson EA, Scouras A, Ellington AD, Marcotte EM, Voigt CA (2005). Engineering Escherichla coli to see light. Nature 438:441–444.</li> |

| - | <li>Muller | + | <li>Muller K, Weber W (2013). Optogenetic tools for mammalian systems. Mol Biosyst 9:596-608.</li> |

| - | <li>Nagel G, Szellas T, Huhn W, Kateriya S, Adeishvili N, Berthold P, Ollig D, Hegemann P, Bamberg E. Channelrhodopsin-2, a directly light-gated cation-selective membrane channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A | + | <li>Nagel G, Szellas T, Huhn W, Kateriya S, Adeishvili N, Berthold P, Ollig D, Hegemann P, Bamberg E (2003). Channelrhodopsin-2, a directly light-gated cation-selective membrane channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:13940–13945.</li> |

| - | <li>Boyden ES, Zhang F, Bamberg E, Nagel G, Deisseroth K. Millisecond-timescale, genetically targeted optical control of neural activity. Nat Neurosci | + | <li>Boyden ES, Zhang F, Bamberg E, Nagel G, Deisseroth K (2005). Millisecond-timescale, genetically targeted optical control of neural activity. Nat Neurosci 8:1263–1268.</li> |

| - | <li>Pathak | + | <li>Pathak GP, Vrana JD, Tucker CL (2013). Optogenetic control of cell function using engineered photoreceptors. Biol Cell 105:59-72.</li> |

| - | <li>Muller | + | <li>Muller K, Engesser R, Schulz S, Steinberg T, Tomakidi P, Weber CC, Ulm R, Timmer J, Zurbriggen MD, Weber W (2013). Multi-chromatic control of mammalian gene expression and signaling. Nucleic Acids Res 41:e124.</li> |

| - | <li>Müller K, Naumann S, Weber W, | + | <li>Müller K, Naumann S, Weber W, Zurbriggen MD (2014). Optogenetics for gene expression in mammalian cells. Biol Chem (accepted) doi: 10.1515/hsz-2014-0199.</li> |

| - | <li>Muller | + | <li>Muller K, Engesser R, Metzger S, Schulz S, Kampf MM, Busacker M, Steinberg T, Tomakidi P, Ehrbar M, Nagy F, Timmer J, Zubriggen MD, Weber W (2013). A red/far-red light-responsive bi-stable toggle switch to control gene expression in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res 41:e77.</li> |

| - | <li>Strickland D, | + | <li>Strickland D, Lin Y, Wagner E, Hope CM, Zayner J, Antoniou C, Sosnick TR, Weiss EL, Glotzer M (2012). TULIPs: tunable, light-controlled interacting protein tags for cell biology. Nat Methods 9:379-384.</li> |

</ol> | </ol> | ||

Latest revision as of 03:10, 18 October 2014

The Light System

Optogenetics in Mammalian Gene Expression

The term "Optogenetics" describes the use of genetically encoded, light-sensing proteins to modulate cellular function or even organismal behavior with high spatio-temporal resolution. In the past few years a large number of versatile light-controlled tools and devices have been developed in all kinds of species, reaching from bacteria [1] to mammalian cells [2]. The introduction of microbial melanopsin into neurons [3] was the first optogenetic approach in mammalian cells and constitutes a milestone in neuronal research [4]. More recently, light-regulated tools have been successfully applied to control diverse signaling processes and gene expression in mammalian cells [2, 5]. Light-inducible gene expression systems follow the yeast two-hybrid principle, using photoreceptors, which allow a number of species to respond to environmental light conditions, as building blocks. In synthetically designed systems, light mediates the recruitment of a transcriptional activation domain to the DNA site. Therefore, either photoreceptors and their light-dependent specific interaction partners are fused to a transactivation domain or to a DNA binding domain, respectively, or light-induced homo-dimerization of photoreceptors is exploited to reconstitute a DNA binding domain. To date, spatio-temporal control over mammalian gene expression is provided by optogenetic gene switches, which are responsive to three distinct wavelengths in the blue, red and UV range [6].

The AcCELLerator Light Systems

In order to choose the light system best suited for our experiments, we considered advantages and disadvantages of all three, such as possible toxic side effects, ease of handling and induction rate. UVB light-inducible gene switches show high induction rates, but UV light has a toxic effect on cells, and was therefore excluded [7]. In contrast, for the red and blue light-inducible systems, the light exposure has minimal toxic side effects.

Due to the longer wavelengths of red light, this system has the additional advantage of high tissue penetration, but on the other hand requires the addition of the small molecule compound PCB to work [8]. Both red and blue light systems are very sensitive to unintentional activation by room light and therefore require special care during handling [7]. Since this problem can be overcome by working under green safe light conditions, we considered both, blue and red light-inducible systems, as suited for our application.

LOV2 Based Blue Light Responsive System

The blue light expression system used for the AcCELLarator capitalizes on the second LOV (Light-Oxygen-Voltage) domain of the protein phototropin of Avena sativa (AsLOV2). LOV domains are small photosensory peptides with up to 125 residues and are used by many higher plants, microalgae, fungi and bacteria to sense environmental conditions. LOV domains, such as the AsLOV2 domain, have been successfully employed in several designs for optogenetic tools. AsLOV2 is N- and C-terminally flanked by α helices, referred to as the Aα and Jα Helix, respectively.

In addition to the LOV2 domain, there are several other parts necessary for light induced expression of target genes. They can be separated into two main modules:

One includes the previously mentioned LOV2 domain that is fused to a Gal4-DNA binding domain (Gal4DBD). This part is constitutively bound to a specific DNA sequence, the Gal4-upstream activator sequence (Gal4UAS) nearby the promotor region of a target gene.

The second part consists of an Erbin PDZ domain (ePDZ) that is fused to a VP16 domain. The VP16 domain can act as a transcriptional activator which recruits DNA polymerase to the gene of interest.

The interaction between ePDZ and the Jα helix of LOV2 is the key process of the system: While in the dark, the Jα chain is not exposed, therefore, the ePDZ-VP16 domain cannot be recruited, and the gene of interest will not be transcribed. Upon illumination, the Jα chain of the LOV2-domain becomes accessible, enabling the second part of the light system, ePDZ fused to VP16, to bind to the Jα chain. VP16 recruits DNA polymerase, thereby leading to transcription of the gene of interest.

Principle of the blue light inducible expression system based on the LOV2 domain of phototropin from the common oat Avena sativa.

Red/Far Red Light Responsive System

Red light inducible gene expression is based on the Arabidopsis thaliana proteins phytochrome B (PhyB) and the phytochrome-interacting factor 6 (PIF6). PhyB is a photoreceptor with an N-terminal photosensory domain, which autoligates its chromophore phytochromobilin (PCB). There are two different states of PhyB: Under red light (660 nm), isomerisation of the chromophore results in the constitution of the active PFR form of the protein, which can bind to PIF6. Far red light illumination leads to reversion back into the inactive PR form and to dissociation of PhyB and PIF6. To capitalize on this light dependent interaction, the N-terminal part of PhyB has been fused to the transactivation domain VP16 derived from the herpes simplex virus. Further, the N-terminal domain of PIF6 was engineered to bind to the tetR-specific operator tetO upstream of the minimal human cytomegalovirus immediate-early promoter PhCMVmin by fusion to tetR, which binds PIF6 to the DNA.

Both light systems are activated by photoexcitation: The LOV-system turns to the „ON“ state, leads to the recruitment and binding of ePDZ to the Jα helix and to induction of target gene expression. Under dark conditions, the system turns back into the „OFF“ state where transcription is terminated [9]. In the red light system, absorption of red light (660 nm) results in the recruitment of PhyB and the fused transcriptional activation domain to the promoter, which subsequently initiates transcription. The system can be immediately shut off by illumination with far red light (740 nm) [8].

In our application, The AcCELLerator, the target gene that is selectively induced by photoexcitation is mCAT-1, a murine cationic amino acid transporter. To explore the possibilities by using this transporter, visit the next page and find out why mCAT-1 is also termed “receptor”.Read More about mCAT-1

References

- Levskaya A, Chevalier AA, Tabor JJ, Simpson ZB, Lavery LA, Levy M, Davidson EA, Scouras A, Ellington AD, Marcotte EM, Voigt CA (2005). Engineering Escherichla coli to see light. Nature 438:441–444.

- Muller K, Weber W (2013). Optogenetic tools for mammalian systems. Mol Biosyst 9:596-608.

- Nagel G, Szellas T, Huhn W, Kateriya S, Adeishvili N, Berthold P, Ollig D, Hegemann P, Bamberg E (2003). Channelrhodopsin-2, a directly light-gated cation-selective membrane channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:13940–13945.

- Boyden ES, Zhang F, Bamberg E, Nagel G, Deisseroth K (2005). Millisecond-timescale, genetically targeted optical control of neural activity. Nat Neurosci 8:1263–1268.

- Pathak GP, Vrana JD, Tucker CL (2013). Optogenetic control of cell function using engineered photoreceptors. Biol Cell 105:59-72.

- Muller K, Engesser R, Schulz S, Steinberg T, Tomakidi P, Weber CC, Ulm R, Timmer J, Zurbriggen MD, Weber W (2013). Multi-chromatic control of mammalian gene expression and signaling. Nucleic Acids Res 41:e124.

- Müller K, Naumann S, Weber W, Zurbriggen MD (2014). Optogenetics for gene expression in mammalian cells. Biol Chem (accepted) doi: 10.1515/hsz-2014-0199.

- Muller K, Engesser R, Metzger S, Schulz S, Kampf MM, Busacker M, Steinberg T, Tomakidi P, Ehrbar M, Nagy F, Timmer J, Zubriggen MD, Weber W (2013). A red/far-red light-responsive bi-stable toggle switch to control gene expression in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res 41:e77.

- Strickland D, Lin Y, Wagner E, Hope CM, Zayner J, Antoniou C, Sosnick TR, Weiss EL, Glotzer M (2012). TULIPs: tunable, light-controlled interacting protein tags for cell biology. Nat Methods 9:379-384.

"

"