Team:Oxford/Results

From 2014.igem.org

(Difference between revisions)

AndyRussell (Talk | contribs) |

|||

| (29 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 65: | Line 65: | ||

<img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2014/b/b7/Oxford_CharacGlen1.png" style="float:left;position:relative; width:80%;margin-bottom:2%;margin-left:10%;margin-right:10%;" /> | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2014/b/b7/Oxford_CharacGlen1.png" style="float:left;position:relative; width:80%;margin-bottom:2%;margin-left:10%;margin-right:10%;" /> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

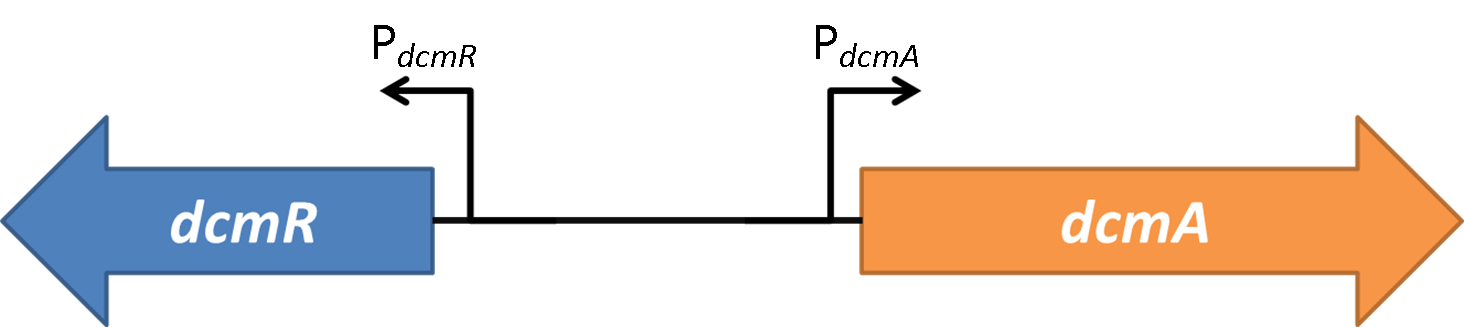

| - | <strong>Figure 2</strong> | + | <strong>Figure 2</strong>(PJ404-PdcmA-sfGFP or Pj404-PdcmA-sfGFP with or without POXON-2 (DcmR)) The effect of adding DcmR to the system (through addition of plasmid POXON-2). Timecourse fluorescence data normalised to OD (600nm) is shown and summarised in the bar charts. Data is shown for both promoter directions (PdcmA and PdcmR). Standard error bars are shown. |

<br> | <br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| Line 76: | Line 76: | ||

<img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2014/1/18/Oxford_CharacGlen2.png" style="float:right;position:relative; width:80%; margin-right:10%;margin-bottom:2%;margin-left:10%;" /> | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2014/1/18/Oxford_CharacGlen2.png" style="float:right;position:relative; width:80%; margin-right:10%;margin-bottom:2%;margin-left:10%;" /> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| - | <strong>Figure 3</strong> | + | <strong>Figure 3</strong>(PJ404-PdcmA-sfGFP or Pj404-PdcmA-sfGFP with or without POXON-2 (DcmR)) OD(600nm) growth curve for all transformed bacteria investigated. The effect of DcmR is measured on the relative stoichiometry of activation of PdcmA/PdcmR. This is shows in the bar charts for stationary phase and for exponential phase. The cut of for exponential phase was set at 600 minutes. |

<br> | <br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| Line 99: | Line 99: | ||

<img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2014/2/2c/Oxford_CharacGlen4.png" style="float:right;position:relative; width:80%; margin-right:10%;margin-bottom:2%;margin-left:10%;" /> | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2014/2/2c/Oxford_CharacGlen4.png" style="float:right;position:relative; width:80%; margin-right:10%;margin-bottom:2%;margin-left:10%;" /> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| - | <strong>Figure 4</strong> | + | <strong>Figure 4</strong> (PJ404-PdcmA-sfGFP or Pj404-PdcmA-sfGFP with or without POXON-2 (DcmR)). The effect of DCM on all both promoters both alone and under the influence of DcmR. Fluorescence measurements were made at mid-log phase with 30mM DCM where added. Yellow charts show the effect of DCM on expression downstream of the PdcmA promoter. Blue charts show the effect of DCM on expression downstream of the PdcmR promoter. Fluorescence measurements were normalised for OD (600nm). |

<br> | <br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| Line 136: | Line 136: | ||

<font style=“font-weight: 600;”>For the bioremediation aspect of DCMation, we managed to achieve the following: </font> <br><br> | <font style=“font-weight: 600;”>For the bioremediation aspect of DCMation, we managed to achieve the following: </font> <br><br> | ||

| - | <h1> | + | <h1>dcmA-sfGFP is expressed in E. coli</h1> |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| + | DCMA-sfGFP can be expressed in E.coli. E. coli cells were transformed with the construct in figure A. Once transformed, the expression of dcmA-sfGFP was induced using IPTG at various concentrations (see figure 2 and 3). It was shown that there is a basal level of expression when using this system however upon induction, there was a significant increase in the protein levels. Following this conformation that dcmA-sfGFP is expressed in E. coli, an assay that has been previously used to measure the activity of DCM dehalongenase (Krausova, 2003) was utilised to access the activity of the protein product. Upon addition of DCM to the cell lysate, there was no change in the NAD+/NADH2 ratio. However, upon addition of the positive control formate, there was a change. This suggests the cell extract has no activity towards DCM. This may be due to a point mutation that was introduced during PCR. Further experiments will have to be performed to determine if this is the reason no activity is observed. <br><br> | ||

| - | (A)A western blot showing the expression of a protein at 62 kDa (the calculated molecular weight of DCMA-sfGFP). The existence of some protein product at 0 mM IPTG suggests that the promoter is slightly ‘leaky’ and allows a basal expression level when no inducer is present. <br> | + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2014/e/e5/DCMAsfGFP.jpg" max-width="20%" style="float:right;position:relative; width:80%; margin-right:10%;margin-bottom:2%;margin-left:10%;"/><br> |

| - | ( | + | <strong>Figure 1</strong><br> |

| + | (A) The IPTG inducible construct used in these experiments.<br> | ||

| + | (B)A western blot showing the expression of a protein at 62 kDa (the calculated molecular weight of DCMA-sfGFP). The existence of some protein product at 0 mM IPTG suggests that the promoter is slightly ‘leaky’ and allows a basal expression level when no inducer is present. <br> | ||

| + | (C) The image shows the expression of GFP under blue LED light in E. coli at various concentrations of the inducer IPTG. The graph quantifies the observed fluorescence, correcting for differences in optical density at 600 nm. Expression significantly increases with IPTG concentration as expected well above the basal level at 0 mM IPTG. <br> | ||

| + | (D)The reaction mechanism of the assay we used to measure DCM dehalogenase activity (Krausova, 2003). The enzyme that catalyses the first step is DCMA, the second step is catalysed by formate dehydrogenase. By adding formate it can be determined which step is not working if the assay does not initially work, thus it acts as a positive control. | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| Line 152: | Line 154: | ||

<img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/parts/8/8c/Westernblot_ABTUNJK.png" style="float:left;position:relative; width:70%;margin-left:15%;margin-right:25%;margin-bottom:10px;" /> | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/parts/8/8c/Westernblot_ABTUNJK.png" style="float:left;position:relative; width:70%;margin-left:15%;margin-right:25%;margin-bottom:10px;" /> | ||

| - | <strong>Figure 2</strong> | + | <strong>Figure 2</strong><br> |

This figure shows the a western blot using anti-his tag antibodies. Subunits B, U, N and K have a C-terminal his-tag each. | This figure shows the a western blot using anti-his tag antibodies. Subunits B, U, N and K have a C-terminal his-tag each. | ||

| + | <br><br> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

<h1>Proteins can be targeted to microcompartments</h1> | <h1>Proteins can be targeted to microcompartments</h1> | ||

| Line 170: | Line 175: | ||

(Figure 3 A- Left) Fluorescence image of E.coli transformed with vectors containing microcompartment tagged sfGFP and the microcompartment<br> | (Figure 3 A- Left) Fluorescence image of E.coli transformed with vectors containing microcompartment tagged sfGFP and the microcompartment<br> | ||

(Figure 3 B - Right) Fluorescence image of E.coli transformed with a vector (pOxon1) containing microcompartment-tagged sfGFP only<br> | (Figure 3 B - Right) Fluorescence image of E.coli transformed with a vector (pOxon1) containing microcompartment-tagged sfGFP only<br> | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

<br><br><br> | <br><br><br> | ||

| - | <br><br> | + | <h1>In order to further our understanding of the systems we are dealing with, we developed the following simulations:</h1> |

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <strong>1. Microcompartment Shape Model</strong>: (see <a href="https://2014.igem.org/Team:Oxford/what_are_microcompartments?#show2" target="_blank">'Predicting the microcompartment structure'</a>) a model that simulates the effect of random point deviations in the microcompartment structure from the perfect icosahedral structure seen in carboxysomes.<br><br> | ||

| + | <img src=" https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2014/7/7f/Microcompartment_shape_2.jpg " max-height="500" style="float:right;position:relative; width:80%; margin-right:10%;margin-bottom:2%;margin-left:10%;"/><br> | ||

| + | <strong>Figure 4</strong> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | The output of the microcompartment shape model is a simulated microcompartment structure (blue) plotted alongside the perfect icosahedral structure of a carboxysome (red) which we used as a starting point for predicting the geometric structure of a microcompartment. | ||

| + | <br><br><br><br> | ||

| + | <strong>2. Prediction of number of enzymes per microcompartment</strong>: (see <a href="https://2014.igem.org/Team:Oxford/what_are_microcompartments?#show4" target="_blank">'Modelling the number of enzymes in a microcompartment'</a>) By modelling enzymes as ellipsoids with axis length dependent on the maximum x,y and z dimensions of our enzyme complexes, this was broken down into the well-documented sand-packing problem. This enabled us to predict the maximum theoretical number of enzymes that can be packed into a microcompartment.<br><br><br><br> | ||

| + | <strong>3. Effect of microcompartments on collision rates</strong>: (see <a href="https://2014.igem.org/Team:Oxford/why_do_we_need_microcompartments?#show3" target="_blank">'Microcompartment rate of collision model'</a>) By using our stochastic diffusion models and discretizing the motion of our simulated particles, this compared the rate of collision of two particles when spatially constrained within a microcompartment versus in unconstrained motion.<br><br> | ||

| + | <img src=" https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2014/e/e1/Collision_diffusion_with_microcompartment.jpg | ||

| + | " max-height="500" style="float:right;position:relative; width:80%; margin-right:10%;margin-bottom:2%;margin-left:10%;"/><br> | ||

| - | < | + | <strong>Figure 5</strong> |

| + | <br> | ||

| + | We have plotted the trajectories of two different molecules along random, stochastically driven discretized paths. What we illustrate here is that the rate of collision (marked in red) is substantially increased through the use of spatial constraints. | ||

| + | <br><br><br><br> | ||

| - | 4. | + | <strong>4. Stochastic diffusion of formaldehyde within microcompartments</strong>: (see <a href="https://2014.igem.org/Team:Oxford/why_do_we_need_microcompartments?#show5" target="_blank">'Modelling the diffusion of formaldehyde inside the microcompartment'</a>) Stochastic diffusion of formaldehyde within cell: Building on the stochastic diffusion models developed previously, we then predicted how the concentration of formaldehyde within a cell would change over time given the restrictions imposed by the microcompartment. |

| + | <br><br><br><br> | ||

| + | <strong>5. Star-peptide model</strong>: (see <a href="https://2014.igem.org/Team:Oxford/alternatives_to_microcompartments#show2" target="_blank">'The Star-Peptide Model'</a>) Our major collaboration with Unimelb iGEM involved modelling the effect of attaching multiple enzymes to a star peptide. This built upon the stochastic diffusion models developed earlier and represents an alternative method of reducing toxic intermediate accumulation to microcompartments. | ||

| + | <br><br> | ||

| + | <img src=" https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2014/1/1b/Star_protein_length_vs_rate_loglog.jpg | ||

| + | " max-height="500" style="float:right;position:relative; width:80%; margin-right:10%;margin-bottom:2%;margin-left:10%;"/><br> | ||

| - | + | <strong>Figure 6</strong> | |

| - | + | <br> | |

| - | + | Plotted here is the logarithmic relationship between star peptide bond length and reaction rate. This was simulated for Melbourne iGEM and suggests that the rate of reaction will be inversely proportional to average peptide length to the power of four. | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

| Line 209: | Line 226: | ||

| - | < | + | <h1>For the containment of our bacteria, we have managed to: </h1> |

| - | For the containment of our bacteria, we have managed to: <br><br> | + | <br><br> |

| - | 1. | + | <strong>1. Synthesise novel agarose beads:</strong> these have a polymeric coating which limits DCM diffusion into the beads. This allows optimum degradation by the bioremediation bacteria, while physically containing the bacteria for safety reasons.<br><br> |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2014/5/56/Oxford_polymer1.jpg" max-height="500" style="float:right;position:relative; width:80%; margin-right:10%;margin-bottom:2%;margin-left:10%;"/> | ||

| + | <strong>Figure 1</strong> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | Illustrated here is the concept design of our biopolymer containers. Not only does the diffusion-limiting polymer coating prevent the concentration of DCM the cells are in contact with from reaching toxic levels but maintains it at the optimum concentration for DCM turnover. Furthermore, by decreasing the size of the beads, this results in a decrease in the depth of penetration for DCM required to reach the bacteria. | ||

| + | <br><br><br><br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <strong>2. Verify the functioning of the biopolymeric beads:</strong> this was done by measuring diffusion using indigo dye. | ||

| + | <br><br><br><br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <strong>3. Design and construct the sensor system: </strong> this was achieved with the aid of 3D CAD software, 1 2 3-D Design, and a 3-D printer .<br><br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2014/7/7c/Oxford_build3.png" max-height="500" style="float:right;position:relative; width:80%; margin-right:10%;margin-bottom:2%;margin-left:10%;"/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <strong>Figure 2</strong> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | This is a simulation we developed of the biosensor case using 3-D CAD software. This was then converted to a 3-D printer-compatible format and printed using ABS plastic. The final print out was a full scale version of the actual design. | ||

| + | <br><br><br><br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <strong>4. 3D print a cartridge to hold our biosensor bacteria:</strong> this sensor was designed to be easily replaced by a user.<br><br><br><br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <strong>5. Construct a prototype circuit:</strong> the circuit lights up when the photodiodes detect light emission from our biosensing bacteria that are contained in the cartridge. This lets the user have a simple yes/no response to whether the contents of the container are safe for disposal.<br><br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2014/6/6a/Oxford_light_circuit.png" max-height="500" style="float:right;position:relative; width:80%; margin-right:10%;margin-bottom:2%;margin-left:10%;"/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <strong>Figure 3</strong> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | The electronic circuit shown above picks up incoming light from the sfGFP at the photodiode and through several amplification and offset steps manipulates the light level into a useable readable signal. This signal is then compared to a threshold safe value and can illuminate a red or green LED to indicate if the water is DCM contaminated or not. | ||

| + | <br><br><br><br> | ||

| + | <br><br> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

Latest revision as of 03:47, 18 October 2014

"

"

Figure 2

Figure 2

Figure 1

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 3